A not so brief introduction to the concept of Period

Last updated on February 21st, 2025 at 03:19 pm

As Schönberg stated in his book on musical composition[1]Arnold Schönberg, Gerald Strang, and Leonard Stein. Fundamentals of Musical Composition (London: Faber and Faber, 1967), 1 and 21., a piece of music is organized some way or the other to make it intelligible or comprehensible. See also my post Books by Schönberg and Ratz. One way to achieve this is to present the musical ideas in a structured way. In (art) music this is called form.

The two most elementary forms to present a musical idea or theme are the sentence and the period. Both deal with the repetition of a so called basic (musical) idea. The repetition is a manner to improve the comprehensibility (getting familiar with the musical idea). Each of these concepts deal with repetition in a different way.

This post is about the period. The post about the sentence can be found here.

In general notes on analysis you can find some remarks on abbreviations, notation and concepts. The books that I have been consulting can be found in consulted literature. The music examples are made in Musescore 4.

Again I want to thank Menno Dekker – my former professor of music theory at the conservatory of Amsterdam – for the very useful discussions I have had with him about the period. He also kindly provided me with some examples.

Whereas the concept of sentence can be defined pretty straight forward, the definition of period is not so unequivocal. To get some guidance I looked into four sources, in chronological order: Schönberg[2]Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition., Caplin[3]Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998)., Hepokoski & Darcy[4]Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006). and Laitz[5]Steven G. Laitz, The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis and Listening (4th Ed (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2016).. As Hepokoski & Darcy state that they use predominantly the terminology advocated by Caplin[6]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 69., I will focus on the other three.

Still a brief introduction to the concept of period

Before going into any detail I would like to point out that in thinking about the period two well-known aspects in classical music play an important role: the first one being the melodic/motivic aspect and the second one being the harmonic aspect.

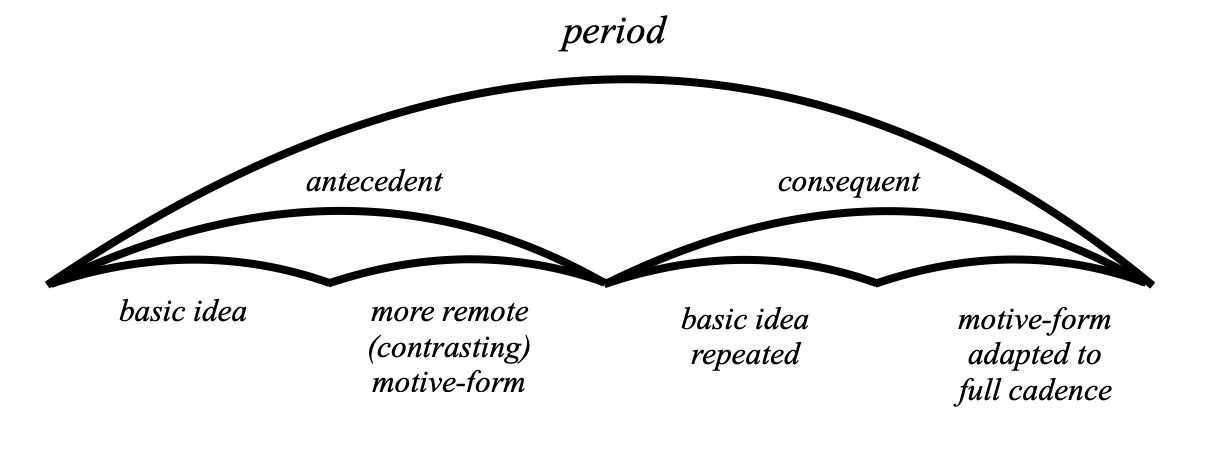

Just to let you in on the secret: the “default” period consists of two 4 bar phrases the first one of which is called antecedent and the second one consequent. In the default setting the antecedent starts with a two bar basic (musical) idea which is not immediately repeated (as in the sentence) but only at the beginning of the consequent (the second 4 bar phrase). The second half of the antecedent consists of something else then the basic idea. What that might be is discussed below.

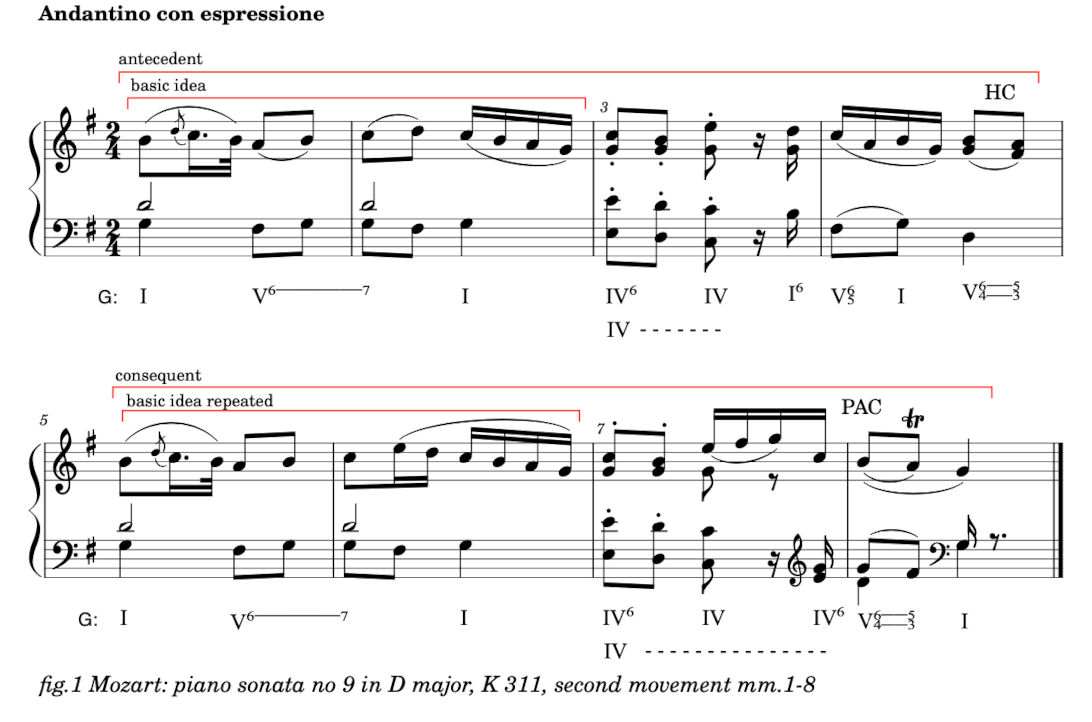

Figure 1 gives an example of a straightforward period.[7]example cited from: Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 41. The harmonic analysis is mine. Notice that mm.5-6 (the beginning of the consequent) are almost an exact copy of mm.1-2: the repetition of the basic idea.

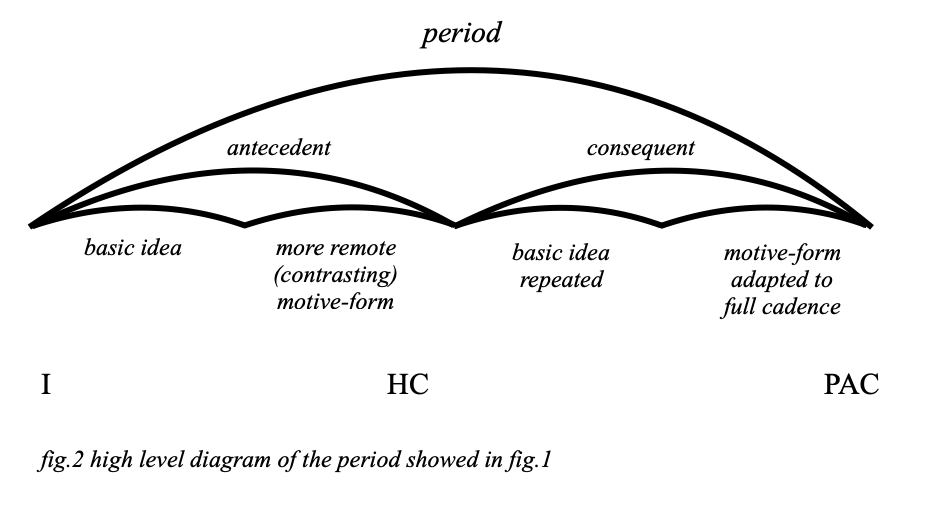

As far as the harmonic aspect is concerned, the ending of the antecedent and consequent are quite stereotypical: a half cadence (I:HC) in the tonic to end the antecedent and a stronger perfect authentic cadence (I:PAC) also in the tonic to close the whole period. And so is the harmonic start of the consequent: on the tonic of the period (I).

Figure 2 shows the diagram of this period. The terminology used for the second half of the antecedent comes from Schönberg and will be explained in the paragraph on The period according to Schönberg.

If you are looking for a brief introduction to the period you can stop reading here because this represents by far the most periods encountered in classical music. However there is a lot more to say about the period and there are a lot more possibilities, especially harmonically but also melodically/motivically. I will address all that in the paragraphs to come.

The period according to Schönberg

As stated in the introduction of this post (and in the post about the sentence) Schönberg is concerned with the comprehensibility of compositions. Remember that his book is intended to teach musical composition and he explains that repetition is important for the comprehensibility. So his starting point is the melodic/motivic aspect.

As already explained, in the period the repetition of the basic idea is delayed to the second half of the phrase, the consequent. The second half of the antecedent consists of “more remote (contrasting) motive-forms”[8]Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 25. according to Schönberg (mm.3-4 in fig.1).

In chapter three of his book he explains how to make variations on a given motive. They are categorised by the aspect that is being varied: rhythm, intervals, harmony and melody, 19 ways in total to vary a motive.[9]Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 10. Some variations stay close to the original while in others it is more difficult to recognise the original. More remote motive-forms belong to the latter category.

Schönberg then emphasizes that the whole phrase (period) is divided in an antecedent and a consequent by means of a caesura which occurs in the fourth measure of each. He compares the caesura with a comma or semicolon in texts.[10]Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 25. The caesura occurs both in the melody and the harmony.

He continues to explain that in the majority of cases the antecedent ends on the dominant (V), often after a cadence (in that case a half cadence [HC]), to add that an ending on I is also possible (see Laitz’s sectional period). The consequent ends on I, V or III (in minor keys) with a full cadence. These cadences are the way in which the caesura takes shape as far as the harmonic aspect is concerned in both the antecedent and the consequent.

The consequent repeats the antecedent and can be varied in the first two bars, but must be varied in at least the last bar because the full cadence must be made possible. Schönberg remarks that the melody loses characteristic features because these aspects ask for a continuation, and the melody must be adapted to the cadential harmonies.[11]Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 30. This reduction of characteristic features is nowadays called liquidation.

Perhaps nice to note that Schönberg starts the paragraph on periods with:

Only a small percentage of all classical themes can be classified as periods. Romantic composers make still less use of them.[12]Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 25.

to subsequently give 66 examples of periods from Bach to Brahms. Some of these examples will be discussed later on.

The period according to Caplin

To start immediately with the opening phrase of chapter 4 on the period of Caplin’s book Classical Form:

The most common tight-knit theme-type in instrumental music of the classical style is the eight-measure period.[13]Caplin, Classical Form, 49.

It is important to notice that the scope of Caplin’s book is the classical style and more in particular the music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. Therefore he restricts himself far more in scope then Schönberg, who didn’t mention any restrictions at all.

I didn’t do any research on the occurrences of periods and sentences in classical music, so I cannot decide who is right, Schönberg or Caplin. Apparently they disagree on this subject. But not so on many others. Caplin continues to build on the foundations of Schönberg. Caplin is more explicit about a number of possibilities in the melodic/motivic aspect as well as in the harmonic aspect and introduces some additional terminology accordingly. Let’s see.

The melodic/motivic aspect

Caplin largely sticks to Schönberg’s definition of the period. The second half of the antecedent [of which Schönberg said it consists of more remote (contrasting) motive-forms] is called the contrasting idea by Caplin.

In a footnote he mentions the fact that Schönberg considers only periods in which the beginning of the consequent is a repetition of the basic idea. In the literature this is often called a parallel period as opposed to a period in which the beginning of the consequent is not a copy of the basic idea. These are called contrasting periods. Caplin continues to state in the footnote that his definition of period will also restrict itself to the parallel period. The contrasting period will be called a hybrid theme in Caplin’s terminology.[14]Caplin, Classical Form, 49, footnote 1.

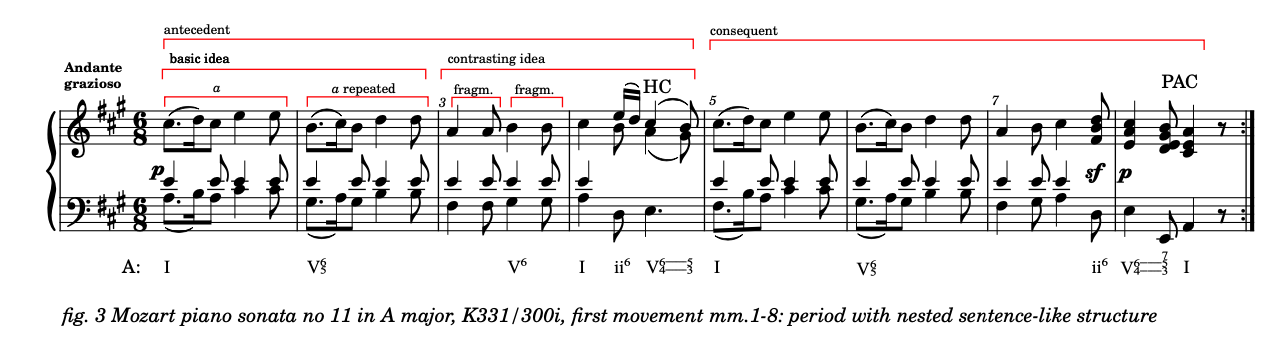

Two more things are mentioned about the melodic/motivic aspect. Firstly Caplin mentions that contrasting ideas often have characteristics that are also found in the continuation of a sentence, like fragmentation, harmonic acceleration or even a stepwise sequence.

Secondly he states that antecedents can have a sentence-like structure in which a basic idea in fact consists of a one measure motive which is repeated in the second bar. This reinforces the idea of the contrasting idea as continuation in which also fragmentation can be found. Figure 3 shows an example.[15]cited from Caplin, Classical Form, ex. 4.6, 52. Notice that the harmonies match with what I have called the stereotypical harmonic structure in the brief introduction.

An elaborated example of a period with a nested sentence structure can be found in the subordinate theme of the first movement of Schumann’s third string quartet in A major.

The harmonic aspect

As far as the harmonic aspect is concerned Caplin immediately states explicitly the fact that the cadence at the end of the consequent must be stronger then the cadence at the end of the antecedent. The antecedent ends more open and asks at it were for a completion with a strong closure, in many cases a perfect authentic cadence (PAC). As we have seen this is supported by the melodic/motivic organisation. Caplin summarizes this as follows:

As a result the two units [antecedent and consequent] group tightly together to form a higher-level whole, a relatively complete structure in itself.[16]Caplin, Classical Form, 49.

Much more so then the sentence which has a more open character which invites a continuation.

Caplin, as Schönberg before him, concludes that the majority of antecedents ends on a half cadence (HC), that is to say pretty open and inviting the second half to close the period.

A number of possibilities for the harmonic closure of both antecedent and consequent pass in review but I defer their treatment until I have dealt with Laitz’s classification, which is more systematic and more exhaustive.

The period according to Laitz

Laitz uses a slightly different approach to the period in which he emphasizes the fact that:

Throughout the tonal area (and beyond), composers have relied on the pattern of incompleteness followed by completeness. Because a sense of incompleteness is crucial to the large-scale organisation of tonal music, composers often avoid harmonically closed four-bar units. Instead, they rely on multiple four- or eight-bar phrases that hinge on one another.[17]Laitz, The Complete Musician, 379.

This is consistent with what Leonard Meyer says about completeness in a wider context:

In other words, the mind, […], is continually striving for completeness, stability, and rest.[18]Leonard B. Meyer, Emotion and Meaning in Music (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1962), 128.

Laitz adds that:

Two phrases make a period only when they relate to each other musically, and the second phrase ends with a strong authentic cadence.[19]Laitz, The Complete Musician, 380.

Meyer says about completeness and closure:

Completeness and closure are possible only because the motions presented in music are processes involving relationships between antecedents and consequents.[20]Leonard B. Meyer, Emotion and Meaning in Music, 129. He uses the terms antecedent and consequent in a broader sense but it fits wonderfully in the context of a period.

So in this approach there is no reference whatsoever to the repetition of the basic idea and consequently Laitz’s definition includes the contrasting period in which the consequent does not repeat literally the basic idea of the antecedent.

Remember that Schönberg doesn’t mention this possibility at all as he is preoccupied with the repetition of the basic idea as a means of increasing the comprehensibility. And Caplin refers the contrasting period to the world of hybrid themes (and restricts himself for the period to the definition of Schönberg). Like Schönberg, Laitz imposes no time or style restrictions on himself when dealing with the period.

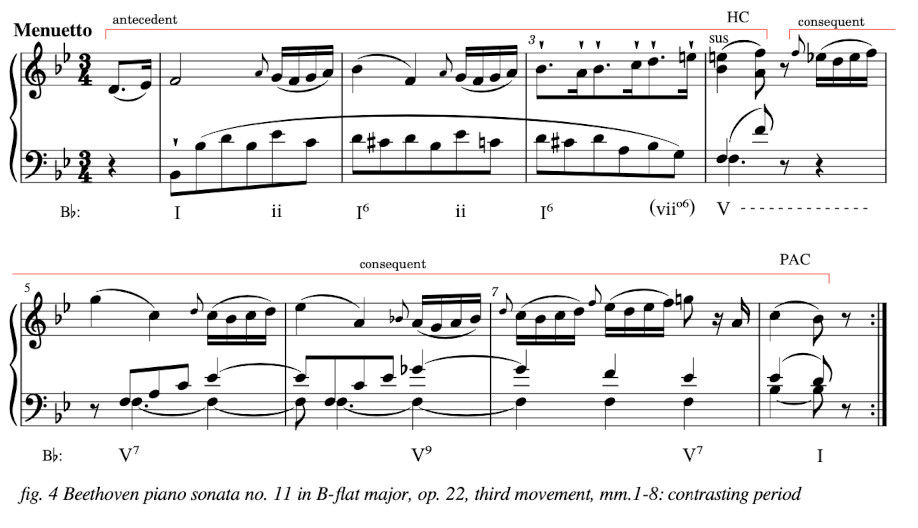

To give you an idea of a contrasting period, fig.4 shows the example used by Laitz.[21]Laitz, The Complete Musician, ex. 15.2B, 381.

As shown the consequent starts with a motive from the antecedent, but not the motive from the start of the antecedent. So it is not a literal repetition of the basic idea and therefore a contrasting period.

Another thing to notice is that the consequent starts on the dominant (m.4 last beat). Laitz calls this a continuous period as the consequent “continues away from the tonic”.[22]Laitz, The Complete Musician, 382.

This in contrast to the period in fig.1 which he would call interrupted. Why interrupted? Because in the consequent the phrase starts all over again and the half cadence (HC) in m.4 is a back-relating dominant that does not resolve to the tonic in m.5.

And so we slowly enter the jargon of Laitz. He distinguishes two other options for the harmonic progression in a period.

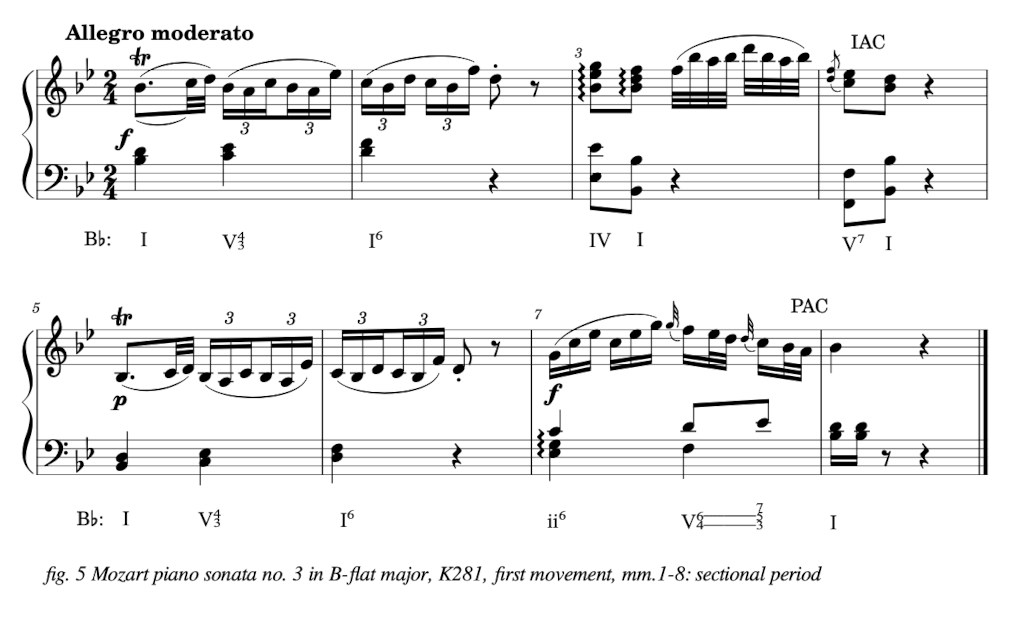

The first one relates to the harmony at the end of the antecedent. So far we have only seen half cadences there; another possibility is that the antecedent ends with an imperfect authentic cadence in the key in which it starts (I:IAC). The consequent than needs to close with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) because this cadence must be stronger then the closure of the antecedent. Both antecedent and consequent are, in a way, a harmonically closed section, and Laitz therefore calls this a sectional period.[23]Laitz, The Complete Musician, 383. Figure 5 shows the example that Laitz uses.[24]Laitz, The Complete Musician, ex.15.3, 383, the roman numerals not given by Laitz are added by me.

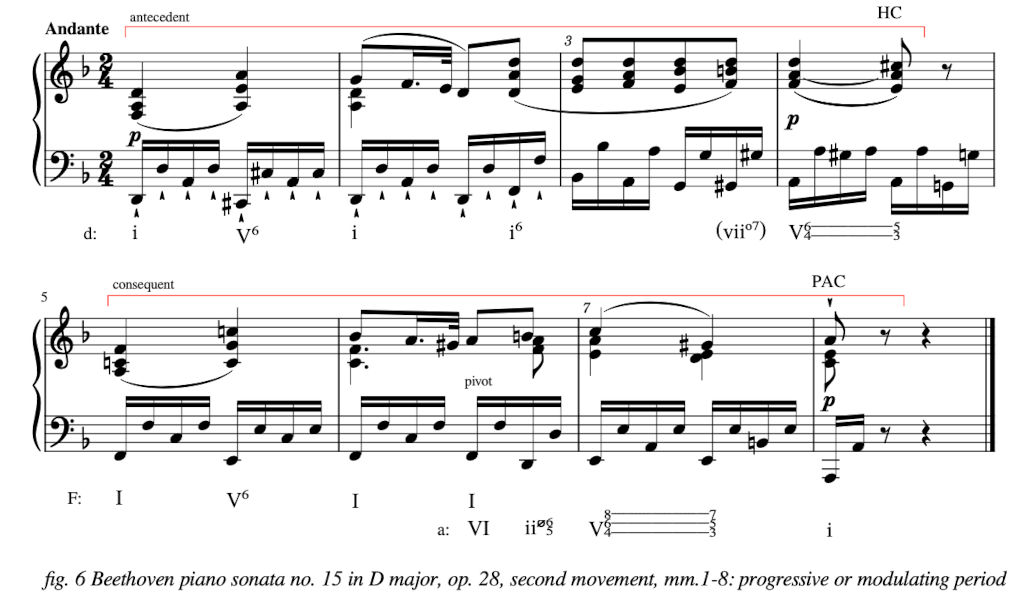

The second option is about the ending of the consequent. Instead of closing with an authentic cadence (I:AC) in the key in which the period starts the consequent can end with an AC in another key. Laitz calls this a progressive period, but I think that the expression modulating period is also widely used. Figure 6 shows Laitz’s example.[25]Laitz, The Complete Musician, ex15.4, 384, the roman numerals not given by Laitz are added by me.

This period ends with a perfect authentic cadence (v:PAC) in a minor, whereas the period starts in d minor. The antecedent ends in a I:HC, but notice that the consequent starts in F major (the III and relative major of d minor). So we would expect that this is also a continuous period but according to Laitz this is not the case. He states:

If two phrases have a weak-strong cadence relationship and there is a key change during the course of the phrases, they form a progressive period. It does not matter whether the cadences reflect characteristics of any other period (sectional, continuous, interrupted). The “progressive” label trumps all other labels because it indicates a change of key.[26]Laitz, The Complete Musician, 384.

There is no explanation why the key change does trump al the other labels. It means that the label progressive (or modulating) can hold quite a few other characteristics which are not made explicit. I wonder why that is.

So Laitz distinguishes eight types of periods along two dimensions:

1. melodic aspect:

a. the consequent repeats the basic idea of the antecedent: parallel

b. the consequent starts different then the basic idea of the antecedent: contrasting

2. harmonic aspect:

a. the antecedent ends on a dominant (half cadence, I:HC): interrupted

b. the antecedent ends on a imperfect authentic cadence (I:IAC): sectional

c. the antecedent ends on a I:HC or X:AC (other then tonic), consequent begins off tonic: continuous

d. antecedent ends on a HC or IAC, the consequent ends on an X:AC in an other key then tonic: progressive or modulating

Figure 7 shows his summary.[27]Laitz, The Complete Musician, 386. This is quite a systematic and exhaustive overview, which nevertheless deserves some comments.

There are two observations to be made here. The first one concerns the already mentioned fact that the progressive (or modulating) label contains a lot of harmonic possibilities for the end of the antecedent and the start of the consequent; as will be shown later there are six possibilities for the parallel and contrasting progressive period each.

The second observation is about the continuous period. In fig.7 we see that is indicated that the antecedent ends on a I:HC or X:AC, i.e. a half cadence in the tonic or an authentic cadence in a key other than the tonic. These are two possibilities, and not one. This is compliant with the difference between an interrupted and a sectional period.

On the other hand there are possibilities in the summary of which no examples are given (and they are not easy to find either).

Inquiry into the theoretical possibilities of the period

Overlooking the playing field so far the conclusion can be drawn that for the harmonic possibilities we have:

1. for the end of the antecedent three possibilities:

i. ending on a I:HC (most common)

ii. ending on a I:IAC

iii. ending on X:AC

2. for the beginning of the consequent two possibilities:

i. starts on I (the tonic of the antecedent)

ii. starts on X, other than I (away from the tonic)

3. for the end of the consequent two possibilities:

i. ending on I:PAC (most common)

ii. ending on X:AC (away from tonic)

So the total of possibilities is 3 * 2 * 2 = 12 for a parallel and contrasting period each, totalling to 24 possibilities.

Of course one may wonder whether these possibilities are only theoretical or if they also occur in real (classical) compositions. I think that is something to find out, if only to understand what is a realistic way to contemplate the concept of period.

As a start I looked into the examples of the three mentioned authors, each with his own approach to the period. Then I looked into examples I encountered myself and last but not least Menno Dekker was kind enough to point out some examples to me. All in all I gathered 14 examples for the possibilities mentioned above. Apart from that I ran into some examples that do not fit in the above categorisation. I’ll point them out near the end of the post.

Table 1 gives an overview of the possibilities for a parallel period. [make the window wide enough to view the table correctly]

Antecedent end

1. I:HC

2.

3.

4.

5. I:IAC

6.

7.

8.

9. X:AC

10

11

12

Consequent start

I

X

I

X

I

Y

Consequent end

I:PAC

X:AC

I:PAC

Y:AC[28]it is possible that Y=X, but not necessarily

I:PAC

X:PAC

I:PAC

Y:PAC

I:AC

Y:AC

I:AC

Z:AC

Example ____________________________________

Beethoven PS no.2 in A, op.2 no.2, iv

Beethoven PS no.15 in D, op.28, ii

Mozart PS no.3 in B-flat, K281, i

Donizetti l’Élisir d’Amore – Quando è bella

Schumann SQ no.3 in A, op.41 no.3, i

no example found yet

Tchaikovsky: Chant sans paroles, op.2 no.5

Grieg: Peer Gynt – Solveig’s Lied

no example found yet

Table 1: possibilities and examples for a parallel period

Table 2 gives an overview of the possibilities for a contrasting period.

Antecedent end

13 I:HC

14

15

16

17 I:IAC

18

19

20

21 X:AC

22

23

24

Consequent start

I

X

I

X

I

Y

Consequent end

I:PAC

X:AC

I:PAC

Y:AC[29]it is possible that Y=X but not necessarily

I:PAC

X:PAC

I:PAC

Y:PAC

I:AC

Y:AC

I:AC

Z:AC

Example ____________________________________

Beethoven VS no.1 in D, op.12 no.1, iii

Beethoven symphony no.2 in D, op.36, ii

Beethoven PS No.11 in B-flat major, op.22, iii

Mozart PS no.10 in C, K330/300h, ii

no example found yet

no example found yet

no example found yet

no example found yet

no example found yet

no example found yet

no example found yet

no example found yet

Table 2: possibilities and examples for a contrasting period

A couple of comments are in order. First of all (and most important) you have noticed that I did not yet find examples for all the (theoretical) possibilities. If you happen to run into one I would be most obliged if you would be willing to share it with me. It will earn you an honourable mention in this post.

The second one concerns the possibilities 4 and 16, both meeting the I:HC – X – Y:AC constraint. As mentioned in footnote 28 Y may be equal to X but it need not be. In example 4 the end of the consequent (Y) is in the key of a minor and does not equal the beginning of the consequent (X) which is in the key of F major. In example 16 however, the end of the consequent (Y) is in the key of C major and that is equal to the beginning of the consequent (X) which is also in the key of C major. So both options do occur in real life. You may wonder why I didn’t split these possibilities. I have considered that but decided against it. The reason is that the number of possibilities would explode. Ultimately it is a trade-off between clarity and insightfulness and thus a matter of tast.

The Schumann example of possibility no.7 is a-typical because not only the consequent starts on ii (b minor) but the antecedent also. The implicit assumption with periods is that the key in which the antecedent starts is the key of the period or viewed more broadly the key of the theme the period is part of. This is not the case in the Schumann example. The home key of the main theme (and of the movement) is A major, but Schumann builds up tension and expectations by starting the movement with a slow introduction in the supertonic (ii) and keeps the tension high at the start of the main theme by continuing in that same key. The cadence at the end of the antecedent (and more so at the end of the consequent) dissolves the tension in the home key. In the near future I will publish a post on the expositions of the three string quartets by Schumann and I will go into this more deeply.

The Tchaikovsky example of possibility no.10 also has a special feature as both antecedent and consequent end with a perfect authentic cadence. Here the incompleteness respectively completeness must be sought in the different keys used: the more unstable g minor (ii) for the end of the antecedent and C major (V) for the end of the consequent.

The Grieg example of possibility no.11 is a double period in a minor, starting in m.10 with upbeat. The antecedent of the larger scale period (mm.10-17) consists itself of a period. The same applies to the consequent. Looking at the larger scale period we see that the antecedent ends with a perfect authentic cadence (III:PAC) in C major (mm.15-16), the relative major of the home key. The consequent starts on V2 of a minor and ends with a i:PAC (mm.23-24). On the lower level the antecedent (mm.10-13) ends on a i:PAC and the consequent (mm.14-17) starts on i. The second lower level antecedent (mm.18-20) is anomalous as it consists of three bars only. The key is predominantly the dominant E major and ends on a kind of half cadence (i:HC), but not in root-position.

Just for fun notice the harmonic progression in m.19. The chord on the second beat has two leading tones to A, the B-flat in the bass and the G-sharp in the alto voice. It can be identified as a double diminished triad on G-sharp in first inversion. As we are in the key of a minor you could spell this as an altered vii0 of a minor, namely a double diminished vii0.

Another possibility is to see it as an augmented sixth chord on B-flat. In that case the orientation is the key of D (major or minor): the chord should be spelled as an It6 (the interpretation I have chosen).

Normally the augmented sixth chords have a predominant function and resolve to the dominant. In this case the dominant would be A major (which would in its turn resolve to D major or d minor). Here the It6 does resolve to A major (m.19, third beat) but the continuation to D does not occur. Instead what follows is another augmented sixth chord (m.19, fourth beat), this time a Fr43. This should be considered in the context of G (major or minor). It resolves to D major (m.20, first beat), the dominant of G, but again the resolution to G does not materialise. Instead the D major chord is chromatically altered to a d minor chord which is followed by the E major chord on the third beat of m.20, the dominant of a minor. In retrospect we realise that the D chords in the first half of m.20 should be regarded as a predominant IV/iv of a minor.

On the first beat of m.22 another augmented sixth chord appears, again a Fr43, this time in a regular function of a predominant of a minor. The double leading tones are the F in the bass and the D-sharp in the alto voice, both leading to E, the dominant of a minor.

And as a final remark on the tables 1 and 2 notice that the possibilities 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22 and 24 correspond with the parallel and contrasting progressive period of Laitz (fig.7).

Some exceptions

As already announced composers do not let themselves be restricted by anachronistically applied models or categorisations. Therefore these models and categorisations should be used as a means to sort out and gain some insight in the common practice and as Hepokoski and Darcy state “… help to provide the vocabulary to describe the nuances of the situation in question.”[30]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 64. They talk about this in the context of the medial caesura and continuous exposition but I think it applies to all models in which we try to capture classical music structures.

So here are a couple of examples that do not quite fit in the categorisations of the period mentioned thus far.

Mendelssohn: Lied ohne Worte, op.38 no.2

The first one is the Lied ohne Worte op.38 no.2 by Mendelssohn.[31]Menno Dekker was kind enough to bring this example to my attention Figure 8 shows the period with which the piece starts.

The antecedent, starting in c minor, ends with a half cadence (III:HC) in the relative major of c minor: E-flat major. The consequent continues with the same motive as the antecedent and therefore this is a parallel period. The key is E-flat major (a continuation of the end of the antecedent) and then modulates back to c minor (m.6) to end on a half cadence (i:HC, m.8). The end of the antecedent is a half cadence in a different key than the home key of the period, a possibility not mentioned in table 1. Moreover both antecedent and consequent end with a half cadence, but in different keys.

As in the Tchaikovsky example (no.10 in table 1) the incompleteness respectively completeness must be sought in the different keys used: the half cadence (III:HC) in E-flat (m.4) gives a much less stable impression than the (i:HC) in m.8. Perhaps the ear links the B-flat chord in m.4 to the VIIAEOL of c minor, a quite unstable chord in that context.

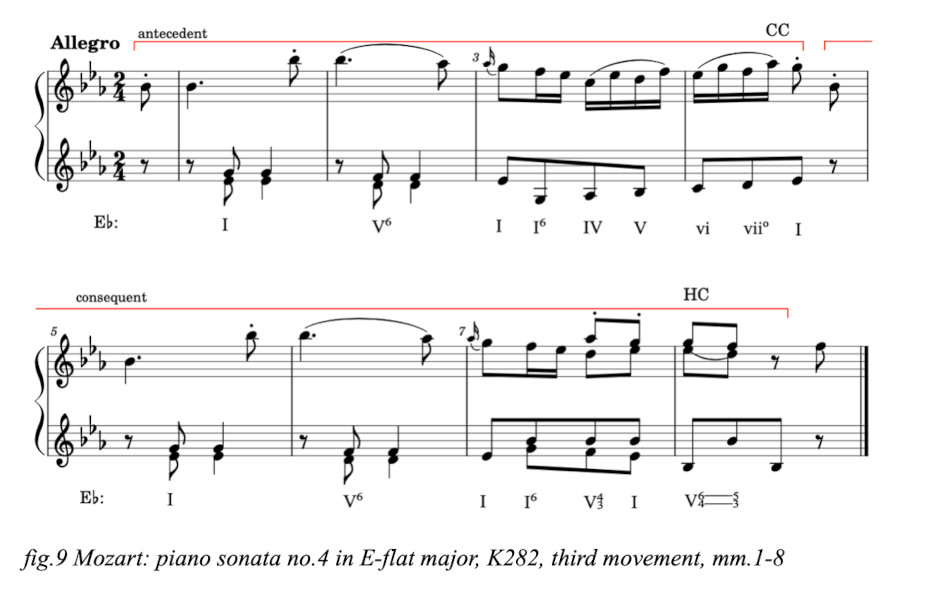

Mozart piano sonata no.4 in E-flat major, K282.

The second example is the third movement of Mozart’s piano sonata no.4 in E-flat, K282. The example is mentioned by Schönberg.[32]Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 39. Figure 9 shows the first eight measures.

The basic idea presented in mm.1-2 is exactly repeated in mm.5-6, so it is not surprising that Schönberg takes this as an example as the melodic/motivic aspect fully meets the requirements of a (parallel) period. The harmonic aspect is different however. Taking into account what Caplin and Laitz say about the endings of the antecedent and consequent this example hardly meets the constraints. In m.4 there is a vii0 – I progression which is not an authentic cadence. Laitz calls this a contrapuntal cadence (CC), a special type of imperfect authentic cadence (IAC).[33]Laitz, The Complete Musician, 172. So one could say this is not a very strong cadence. But when looking at m.8 we do not find a (perfect) authentic cadence (PAC) which would be stronger than the CC, but a half cadence (I:HC) in the tonic. This harmony makes it sound like an open ended continuation of a sentence, but there are no other features of a continuation (fragmentation, liquidation nor acceleration of the harmonic rhythm). So the conclusion must be that although melodically this phrase does fit in the concept of a parallel period, harmonically it falters. One might consider the hybrid themes as defined by Caplin[34]Caplin, Classical Form, Chapter 5. but the two eligible categories (antecedent + continuation and antecedent + cadential) do not fit completely. As mentioned the consequent does not have the features of a continuation so the first possibility drops out. The second (antecedent + cadential) might be applicable although the exact repetition of the basic idea in mm.5-6 strongly indicates a parallel period. Furthermore the cadential part of the second option suggests a rather strong cadence as the examples used by Caplin also show. As shown that is not the case here.

Brahms: string quartet in c minor, op.51 no.1

The third and last example is again an example mentioned by Schönberg: the third movement of Brahms’s first string quartet in c minor, op.51 no.1. In his comments on periods by romantic composers he says:

The examples from Brahms are especially interesting because of their harmony. They differ from the classic examples in a more prolific exploitation of the multiple meaning of harmonies.[35]Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 30.

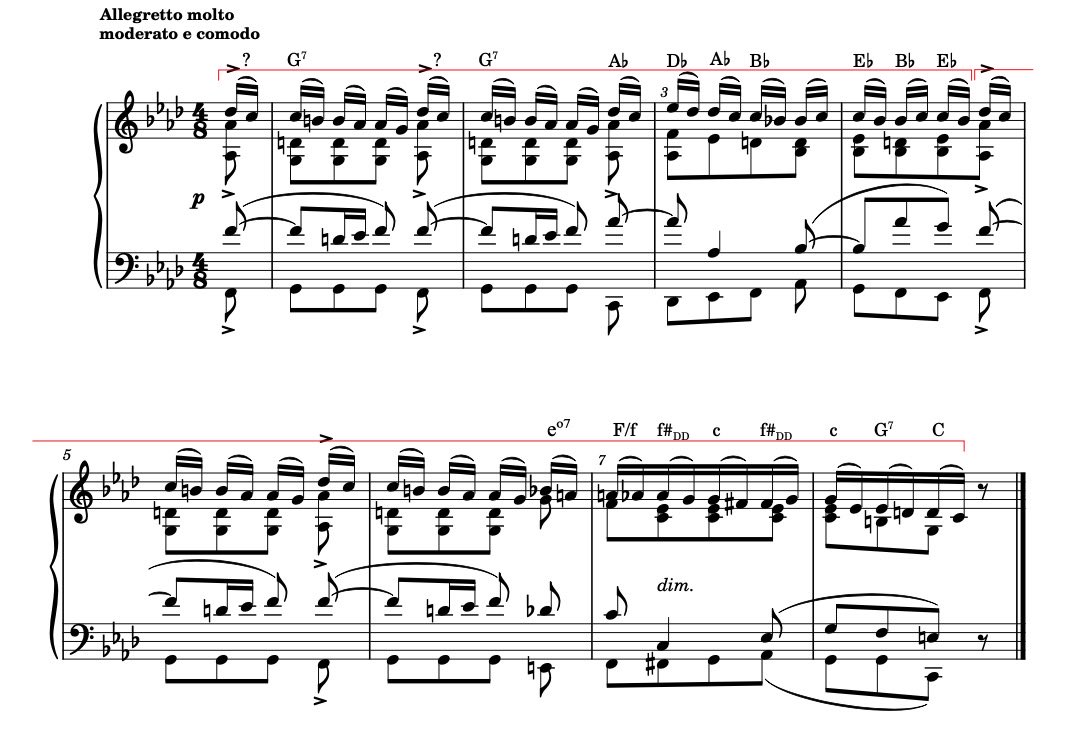

And that is how it is. Figure 10 shows the first eight measures of the period of this movement with only the names of the chords.

fig 10 Brahms string quartet no.1 in c minor, op.51 no.1, third movement, chords

The brackets indicate the antecedent and consequent of the period. As the start of the consequent (m.5 with upbeat) equals the start of the antecedent we are looking at a parallel period.

The movement is in f minor and there are chords that belong to the key of f minor: the A-flat and D-flat major chords in mm.2-3 as mediant respectively submediant. The B-flat chord in mm.3-4 does not belong to the key of f minor, but can easily be interpreted as the applied dominant of E-flat major. E-flat major does belong to f minor as the VIIAEOL. The question is whether this is the right interpretation.

As of the end of m.6 we find an e diminished seventh chord, the vii07 of f minor (or major). This leads as expected to the F major/minor combination. Ignoring the f-sharp double diminished chords in m.7 for the moment, what follows is a c minor chord (vAEOL of f minor). The G dominant seventh chord in m.8 clearly does not belong to f minor, but can again easily be interpreted as the applied dominant of the last chord of this period: C major, the dominant of f minor and in this context with a picardy third.

Remarkable is the G dominant seventh chord in mm.1-2. What is it doing there in a f minor context? Schönberg gives an interpretation:

But in m.7-8 Brahms finally identifies m.1-2 and 5-6 as pertaining to c-minor, or, more accurately to de v-region of f-minor.[36]Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 31.

So this means we should consider the whole period in c minor. Remember that c minor is the key of the string quartet as a whole. Figure 11 shows the period with the roman numerals added according to this interpretation.

The first conclusion to be drawn is that apparently the movement starts with a period in c minor whereas the key of the movement is f minor. My professor at the conservatory of Amsterdam – Menno Dekker – has a list of ten ways in which romantic composers could provide for surprises that were not customary in the classical style. One of them is beginning a piece or movement off key. I think that applies here. The movement eventually does turn to f minor but that is out of scope in this context.

So analyzing the period in c minor the A-flat major chord on the fourth beat of m.2 should be interpreted as a deceptive resolution (VI of c minor) of the G dominant seventh chord. What follows is a pretty strong cadence in E-flat major. This is to be read as a half cadence (HC) in the VI of c minor, A-flat major. The antecedent thus ends on a VI:HC, something not provided for in table 1. In fact it is the same exception as in the first example of exceptions: the Mendelssohn Lied ohne Worte. But here we are further removed from the tonic as the whole period is off key. Schönberg comments on these measures as follows:

The deviation in m.3 toward E-flat is surprising. While E-flat might be the dominant of the mediant region (relative major), it is actually treated like a tonic on VII [Schönberg is talking f minor here].[37]Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 31.

If the whole period is to be viewed in the context of c minor than Schönberg’s mediant region should be called the submediant region of c minor (A-flat as the VI of c minor). When Schönberg says that E-flat is treated like a tonic it means it has the appearance of a modulation to E-flat. The start of that modulation would be on the second beat of m.3 as the D-flat major chord on the first beat of m.3 does not have an obvious function in E-flat major. Notice that Schönberg says that it is treated like a tonic, but actually his analysis treats it as a the mediant region of f minor. I think this is a nice example of multiple meanings of harmonies as mentioned in the first quote.

One remark about the surprise character of the end of the antecedent: what else could Brahms have done here? Well, the most obvious option would have been to have written a half cadence (HC) in c minor. Than the whole period would have been rather classical (harmonically speaking) and would fit in what I called the stereotypical harmonic structure. But he chose a HC in A-flat. Why A-flat? As we have seen A-flat is the VI of c minor and makes for a nice deceptive resolution of the G dominant seventh chord, which is a forward reference to c minor. But A-flat major is also the relative major of f minor and together with the ambiguous upbeats this is another forward reference, this time to f minor, the key of the movement.

The consequent ends with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in c minor (with the picardy third). The predominant region starts with the applied dominant of the predominant F major/minor (fourth beat of m.6). After the predominant there are two double diminished seventh chords on the raised fourth scale degree (on the second and fourth beat of m.7) connected by a passing i64. The double diminished seventh chords are in different positions. The second one (on the fourth beat of m.7) is in first inversion and is an augmented sixth chord (a GER65). Both chords have the double leading tones to the fifth scale degree (the dominant) of c minor: the A-flat in the bass and the F-sharp in the soprano.

A last remark concerns the upbeat to the whole period (and also the fourth beats of m.1, 4 and 5).

In fig.10 these beats have a question mark and in fig.11 two possible roman numerals, N6 and iv. The point is which note in the soprano is considered to be the chord note. The D-flat with accent or the C natural? If we take the D-flat than the chord is a D-flat major chord in first inversion and thus a Neapolitan sixth chord in c minor. Function: predominant.

If, on the other hand, we take the C natural we end up with an f minor chord in root position, the predominant iv of c minor and obviously the function is also predominant.

A nice ambiguous start for a movement in f minor with an opening in c minor (the vAEOL of f minor). Both interpretations are valid although the accent on the D-flat might tend to the Neapolitan interpretation.

To summarise: the third movement is a movement in f minor which starts with a period in c minor. The antecedent ends with a half cadence in the deceptive VI of c minor and the consequent ends with a perfect authentic cadence in c minor, but with a picardy third (and the resulting chord is the dominant of f minor).

Notes

| ↩1 | Arnold Schönberg, Gerald Strang, and Leonard Stein. Fundamentals of Musical Composition (London: Faber and Faber, 1967), 1 and 21. |

|---|---|

| ↩2 | Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition. |

| ↩3 | Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998). |

| ↩4 | Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006). |

| ↩5 | Steven G. Laitz, The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis and Listening (4th Ed (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2016). |

| ↩6 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 69. |

| ↩7 | example cited from: Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 41. The harmonic analysis is mine. |

| ↩8 | Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 25. |

| ↩9 | Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 10. |

| ↩10 | Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 25. |

| ↩11 | Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 30. |

| ↩12 | Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 25. |

| ↩13 | Caplin, Classical Form, 49. |

| ↩14 | Caplin, Classical Form, 49, footnote 1. |

| ↩15 | cited from Caplin, Classical Form, ex. 4.6, 52. |

| ↩16 | Caplin, Classical Form, 49. |

| ↩17 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, 379. |

| ↩18 | Leonard B. Meyer, Emotion and Meaning in Music (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1962), 128. |

| ↩19 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, 380. |

| ↩20 | Leonard B. Meyer, Emotion and Meaning in Music, 129. He uses the terms antecedent and consequent in a broader sense but it fits wonderfully in the context of a period. |

| ↩21 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, ex. 15.2B, 381. |

| ↩22 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, 382. |

| ↩23 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, 383. |

| ↩24 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, ex.15.3, 383, the roman numerals not given by Laitz are added by me. |

| ↩25 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, ex15.4, 384, the roman numerals not given by Laitz are added by me. |

| ↩26 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, 384. |

| ↩27 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, 386. |

| ↩28 | it is possible that Y=X, but not necessarily |

| ↩29 | it is possible that Y=X but not necessarily |

| ↩30 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 64. They talk about this in the context of the medial caesura and continuous exposition but I think it applies to all models in which we try to capture classical music structures. |

| ↩31 | Menno Dekker was kind enough to bring this example to my attention |

| ↩32 | Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 39. |

| ↩33 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, 172. |

| ↩34 | Caplin, Classical Form, Chapter 5. |

| ↩35 | Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 30. |

| ↩36, ↩37 | Schönberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 31. |

Recent Comments