Schumann string quartet no 3 – an analysis

Last updated on September 5th, 2024 at 12:56 am

Table of contents

Introduction

As I was working on the analysis of Schumann’s piano quartet in E-flat major, op.47, I read the book by John Daverio on Schumann.[1]John Daverio, Robert Schumann: Herald of a “New Poetic Age” (New York etc.: Oxford University Press, 1997). A remarkable feature of the piano quartet is that the exposition has no second theme and that the articulation of the dominant is late in the exposition (find my analysis of the first movement of the piano quartet here). Daverio compares the way in which Schumann and Haydn handle the sonata form and remarks “Similarly, Haydn’s teleological sonata forms […] find a counterpart in the delayed articulation of the dominant that characterizes the exposition of the first and last movements of Schumann’s Opus 41, no 2 [string quartet]”.[2]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 251.

That made me curious so I started looking into the second string quartet. But then my curiosity went further and I wondered what Schumann did in the other string quartets. After all he wrote them in a time span of seven weeks: beginning of June to the 22nd of July 1842.

After drawing some sketches for comparing the quartets I decided to write a post about the comparison. But before you can compare them you need to analyse them. So I ended up with a project that will provide for a small series of four posts: one for the analysis of each of the string quartets (the exposition of the first movements only) and a fourth post for the comparison.

This is the third post in this mini series and deals with the third string quartet in A major, op.41, no.3. The post on the analysis of the first string quartet in a minor, op.41 no.1 can be found here and the post on the second string quartet in F major can be found here.

I again want to thank Menno Dekker – my former professor at the conservatory of Amsterdam – for the very useful discussions I have had with him. It keeps improving my understanding of music and more particular music analysis. Our relation has grown into a genuine friendship with the music theory and analysis as a perpetual source of inspiration.

Historical context

In the beginning of 1842 Schumann had quite a difficult time, as a matter of fact it was “the first major crisis of Schumann’s married life”.[3]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 242. Clara was on a concert tour in northern Germany and Robert accompanied her. After one of the concerts (in Oldenburg on the 25th of February) Schumann was not invited for the after concert party. Clara decided to attend on her own and Robert was furious and returned to Leipzig alone.[4]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 243. In the weeks to follow – spent alone in Leipzig – “Schumann occupied himself with exercises in counterpoint and fugue”.[5]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 244. As will be shown hereafter the fruits of this investigation in counterpoint and fugue are readily traceable in the string quartets opus 41.

The strings quartets are dedicated to Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, a good friend of Robert Schumann.

Practical information

In this text a lot of references are made to the score of the string quartet. This is done by means of the measure number (always within the first movement). Ideally you have a score with measure numbers at your disposal. A score can easily be downloaded from IMSLP.

In general notes on analysis you can find some remarks on abbreviations, notation and concepts. Some books that I have been consulting can be found in consulted literature. At least all references made to literature in the notes should relate to entries in the consulted literature. The musical examples are made in Musescore 4.

As for a notational convention of major and minor keys: I will use capitals for major keys and lower-case letters for minor keys. For major keys I will often add the word major and for minor keys the word minor, but in music examples and diagrams the words major and minor will in general be omitted. So B major or B for B major and b minor or just b for b minor.

Finally it must be mentioned that although automatic adjustments are made to view these posts on tablets as well as mobile phones, they can best be accessed on a computer/laptop. The reason being that there are various tables and lists (like abbreviations) of which the columns will appear one beneath the other (especially on a mobile phone), in which case coherence will be lost.

Schumann: the string quartet in A major, op. 41 no. 3

This string quartet is the third and last string quartet Schumann wrote between 8 and 22 July 1842. It is also the last string quartet ever, he wrote. The quartet has a different character than the other two in so far that the contrapuntal element is less outspoken then in its two predecessors. My impression is that Schumann has found here a more relaxed way in the handling of counterpoint and this makes this quartet very accessible. Also the forms used for the main and subordinate themes differ significantly from those in the string quartets in a minor and F major.

Slow introduction

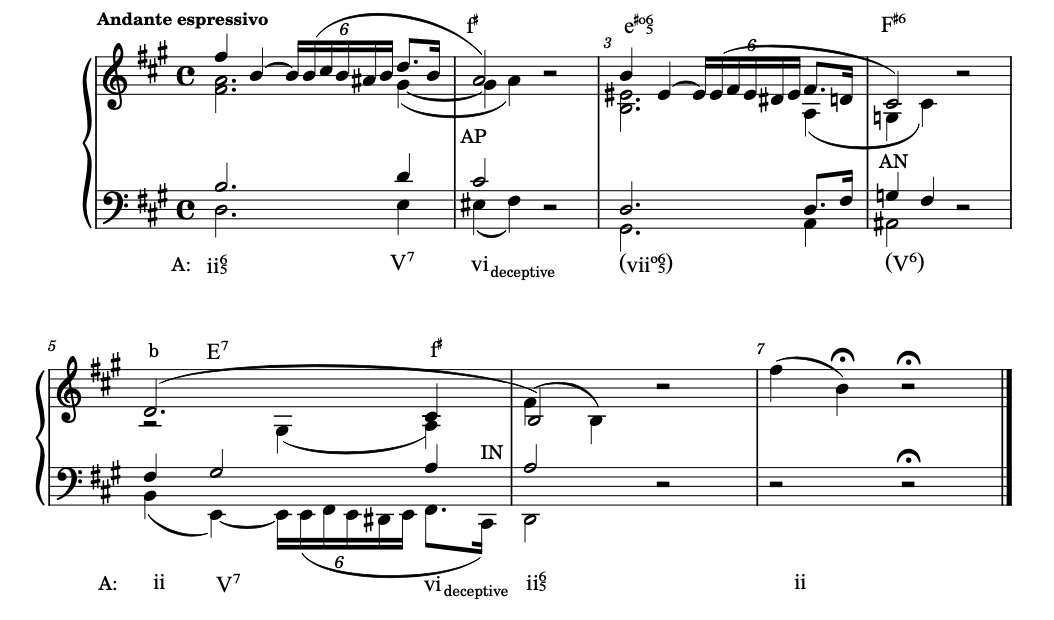

This quartet also has a slow introduction (like the first quartet in a minor), but whereas the first quartet has a slow introduction of 33 bars, the third quartet confines itself to seven bars only. But how ingeniously Schumann did this, especially in connection with the ensuing Allegro molto moderato. Figure 1 shows the piano score of the slow introduction.

fig.1 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, mm.1-7

I included some of the chord names to make the whole harmonic progression more comprehensible.

This third quartet is in the key of A major but in the slow introduction that key can hardly be found. It starts with a b minor seventh chord in first inversion (m.1), followed by an E dominant seventh chord which leads to a f-sharp minor chord (m.2). The b minor returns in m.5 this time in root position and in m.7 there is again a big question mark in b minor. In fact the whole introduction is one big question mark.

This brings to mind Charles Ives’s The unanswered question. Find Leonard Berstein’s explanation here and a video recording here. His question is of course a superlative and in Ives’s composition the question remains unanswered. Schumann’s question is much more tonal and he will provide us with an answer but we have to be patient.

To see that I have analysed the whole progression in the key to come in the Allegro molto moderato: A major (in fact the only logical choice). The first harmony then turns out to be a predominant ii65. This off tonic start is not unprecedented; see for instance Beethoven’s piano sonata in E-flat major op.31 no.3 which starts on the same off tonic harmony (ii65) and also with a falling fifth.[6]I am indebted to Menno Dekker who kindly called my attention to this very comparable opening by Beethoven.

The b minor chord is followed by the dominant of A major, the E dominant seventh chord on the fourth beat of m.1. One expects a resolution to A major but Schumann evades the tonic and resolves deceptively to the vi of A major: f-sharp minor. So here we experience the first question mark. To give the listener the opportunity to contemplate what she just heard and to formulate an expectation, there is a two beat rest in m.2. What could that expectation be? To be sure it is the longing for some kind of closure of the phrase (typically a cadence in A major).

But what does happen next? An e-sharp diminished chord in first inversion followed by a F-sharp major chord also in first inversion. The relation between these two isn’t too difficult: the e-sharp diminished chord is the (applied) vii065 of the F-sharp major. But we have to put that in context.

The first phrase ended with an f-sharp minor chord (m.2), the second with an F-sharp major chord (m.4). The first one mentioned is the (deceptive resolution) vi of A major, the second one turns out to be the (applied) dominant of the second occurrence of b minor in m.5. So no closure whatsoever. In fact the question mark is repeated.

But before that sounds there is again a big pause of two beats (m.4) in which the listener can recover from the surprise just experienced and become aware of an even greater longing for a closure. But no stability is reached (yet).[7]For a great introduction to stability and closure see: chapter IV Principles of Pattern Perception: Completion and Closure in Leonard B. Meyer, Emotion and Meaning in Music (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1962).

In fact the opening phrase is repeated with the motive in the dominant of A major (in the cello, m.5). So the dominant occurs sooner than in the first phrase and leads again to a deceptive resolution on the fourth beat of m.5. Then the phrase ends with the opening statement in b minor (m.6). So here the harmonic rhythm is faster and gives room in the same time span for an additional repetition of the question mark (first half of m.6).

Still no clue where we are! And to heighten the confusion – again after a two beat pause – the question mark is again repeated quite desolate in the first violin (m.7). Five repetitions of this plaintive motive!

So far for a lesson in tension building and creating expectations!

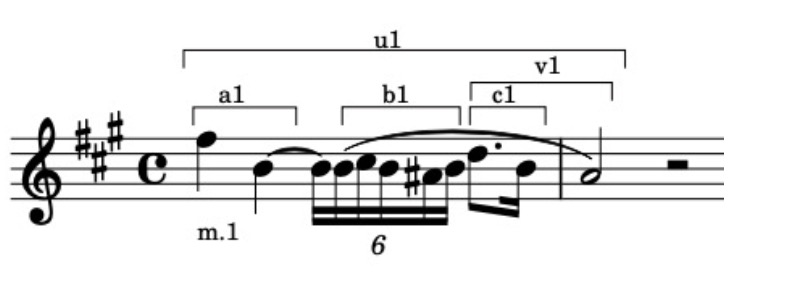

Motives of the slow introduction

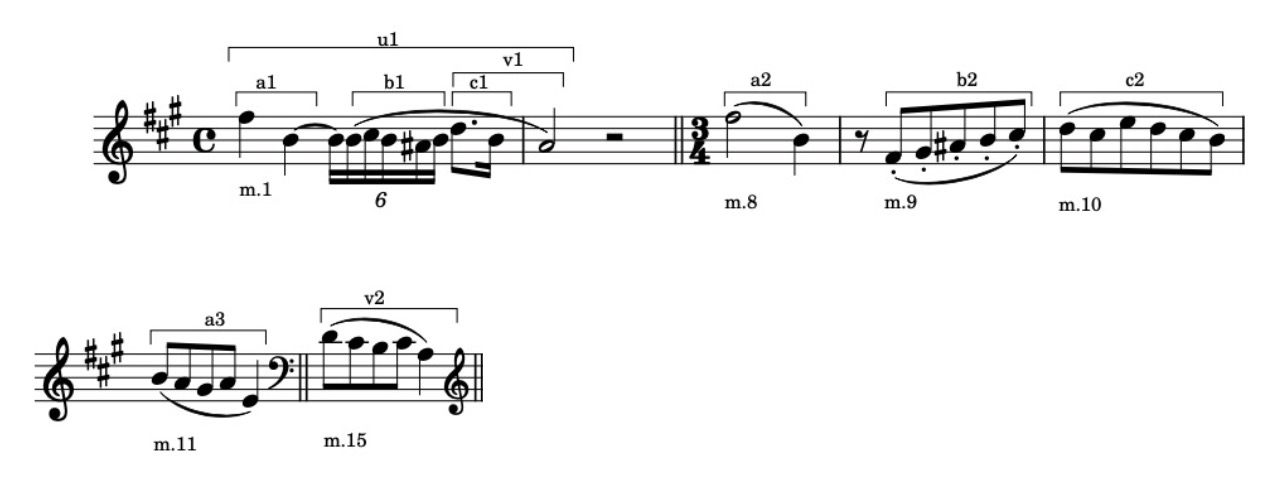

In fact there is only one motive in the Andante espressivo as shown in fig.2. But it is a compound one (u1) and contains several smaller motives. Of course there is the very characteristic melancholic falling fifth motive (a1) with which the quartet starts.

fig.2 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, motives of the Introduction

The different motifs and their variants will be encountered later on. As for the contour of the melody it is clearly a triadic motion (in b minor). It starts with the gap between the fifth to the first scale degree which is then filled up to the third scale degree (the D natural on the fourth beat of m.1). The A natural in m.2 is a surprise in this context and this calls for a return to the B which incidentally happens in m.3, albeit with a quite surprising harmony.

Similarly, the C-sharp in m.4 asks for a return to the D natural which happens in m.5. The interaction with the harmonies gives this whole introduction its magic flavour.

The exposition

The main theme or first tonal area (FTA)

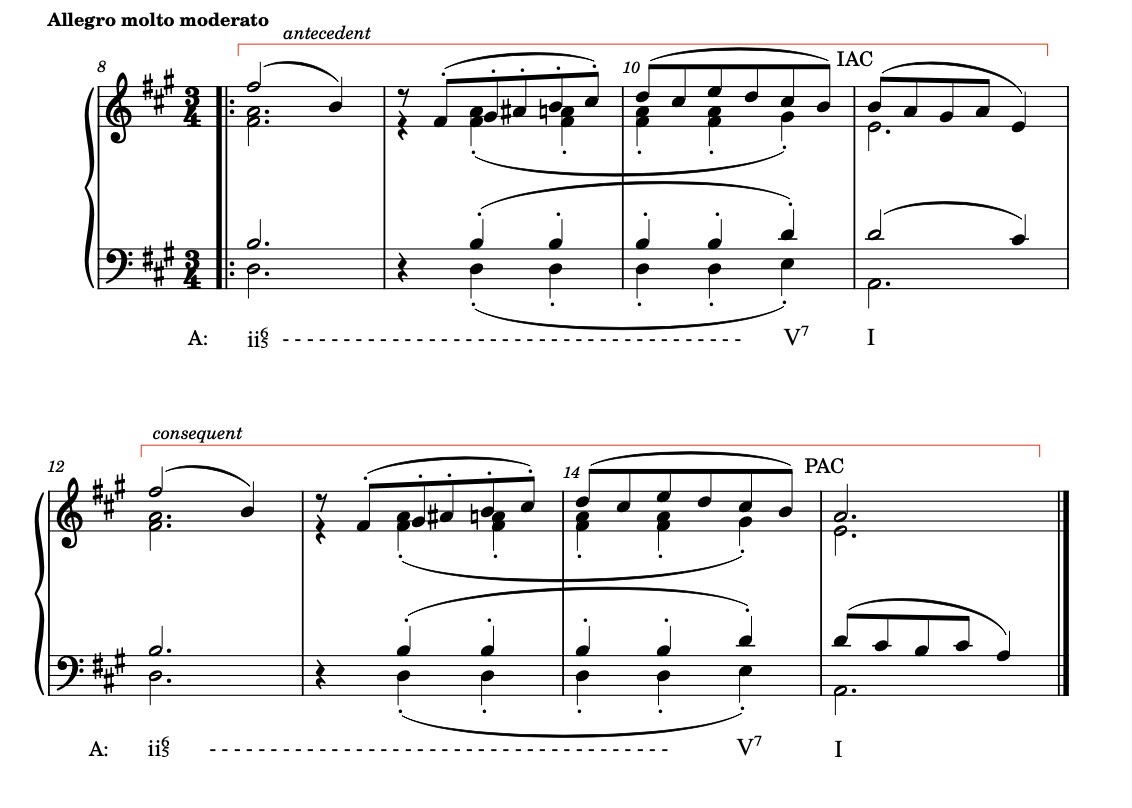

Coming from the Andante espressivo there is a great expectation for a resolution and closure of the question posed there. The first theme of the exposition indeed resolves the matter. Figure 3 shows the piano score of the main theme.

fig.3 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, mm.8-15

The form of this phrase is clearly a period. Look here for my post on the concept of period. It is a parallel period as the beginning of the consequent is identical to the beginning of the antecedent. Measures 8-9 and mm.12-13 are called the basic idea respectively the repetition of the basic idea.

When comparing the basic idea with the opening measure of the Andantino espressivo (m.1) a remarkable resemblance does strike us. In fact the descending fifth F-sharp – B-natural is exactly the same, as is the key in which it occurs: b minor. The listener might be lured to think that she still is in the slow introduction of the Andante espressivo.

But m.9 is the wakeup call: a different continuation with a much faster rhythm.

Ahh … we arrived in a different world then and indeed this phrase ends with an imperfect authentic cadence (IAC) in A major. Look here for some definitions of various types of cadences. At last the resolution we have been waiting for! But as a proper period becomes it is an intermediate completion and the full closure only appears at the end of the consequent with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in A major (mm.14-15).

The Allegro molto moderato has begun and the key has been established.

As it turns out the Allegro molto moderato is (of course) in sonata form and the exposition contains the following elements:

Measure

8-15

16-45

46-90

90-101

Key (relative to A major)

I

I – V/V

V (E major)

V

Table 1: layout of the exposition

The main theme or first tonal area (FTA) has just been discussed but before moving onto the Transition we take a look at the motives of the FTA.

The motives of the main theme

As shown in fig.4 the main theme starts in m.8 with a motive (a2) that has a very strong relationship with the opening motive of the Andante espressivo (a1). Only a slight rhythmic change has been made and as already has been noted before, the listener could easily think that he is still in the Andante espressivo. On close inspection however the difference is clear. There is a change of meter and the first note is prolonged.

fig.4 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, motives up to the main theme

Here the resemblance does not stop. Measure 9 is a connection between the B in m.8 and the D in m.10, as is the ornamental motive b1 between the B and the D in m.1. The rhythm also is quite similar (five notes starting after the beat). Measure 10 is an ornamented fall of a third, corresponding to the fourth beat of m.1.

So in fact the antecedent of the period (mm.8-11) is a variant of the compound u1 motive or – if Schumann first came up with the main theme of the Allegro molto moderato – the u1 motive in the introduction is a variation of the main theme.

The Transition (TR)

The Transition is 30 measures long. A downloadable PDF in piano score format with my annotations can be found here. I think it is possible to structure the Transition as follows:

Measure

16-27

28-35

36-37

38-45

Segment

1

2

3

4

Structure

4+4+4 sequential sentence like structure

4+4 period (main theme in B major)

connecting measures in C major

4+4 hybrid structure: antecedent + continuation

Table 3: layout of the Transition

The Transition: Segment 1

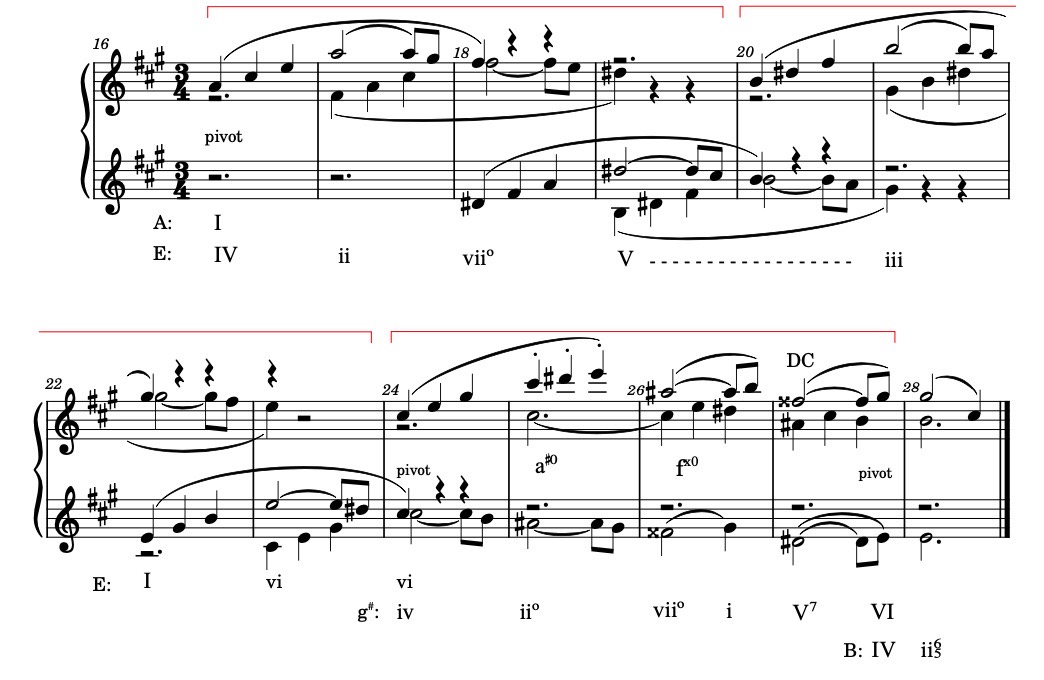

The Transition starts with a segment that has an imitative texture in the four voices. The segment is twelve bars long which can be divided in three phrases of four bars each. Figure 5 shows the score in piano format. Measure 28 is shown for the connection with the second segment.

fig.5 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, mm.16-28

The first two phrases are identical except for the fact that the second one (mm.20-23) is raised one second compared to the first. So it is a sequential progression. The third phrase (mm.24-27) starts with the same motive in the first violin again raised one second. But then it continues differently and ends in a deceptive cadence (DC) in g-sharp minor (m.27).

The motive Schumann uses is simply an ascending triad and every next voice plays the triad a third lower then its predecessor. The quality of the triads differs however as does the quality of the interval of the leap (always thirds).

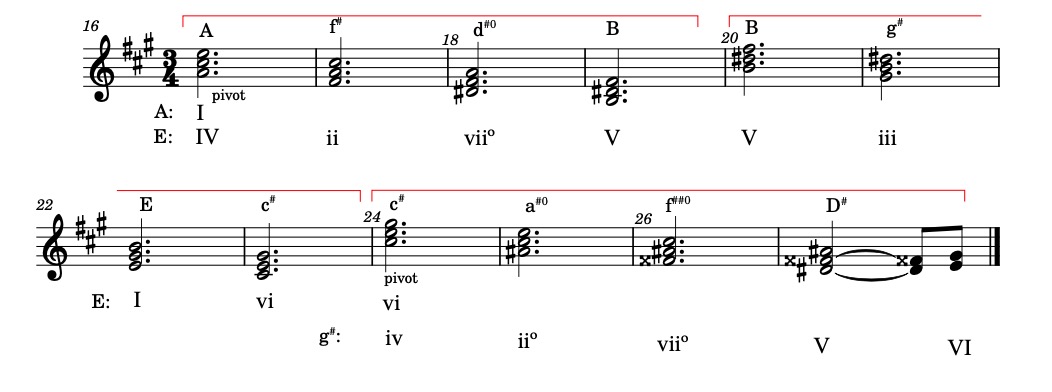

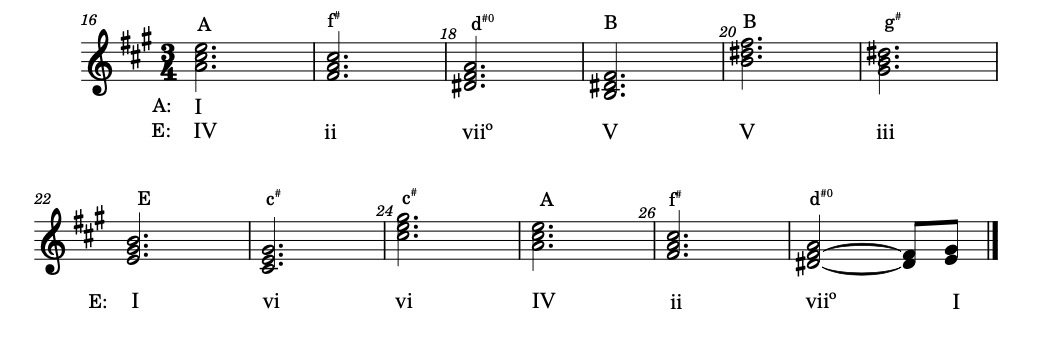

Figure 6 shows the first segment notated as chords with the chord names above and the roman numerals beneath each chord.

fig.6 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, mm.16-28, harmonic reduction

The first chord (m.16) is an A major chord and provides for the connection with the main theme or first tonal area (fig.3). It is however immediately a pivot chord as it can be interpreted as a IV in E major. Why E major? That follows from the chords in mm.18-19. They only fit properly in the key of E major. So the first phrase has been analysed in E major. It should be noted that one can choose to place the pivot chord one bar later (m.17) because that chord can be interpreted as a vi in A major. I chose not to do so because of the analogy with the third phrase.

So we find here a descending third progression and Schumann chose to make it diatonic (and not chromatic) in the key of E major. That explains the different quality of the chords. Because as you probably know, a ii in E is a minor chord and a V is a major chord and so on.

Another interesting point is that in m.20 (the start of the second phrase) the B major chord (m.19) is repeated one octave higher, and then the descending third progression simply continues. And still in the key of E major. Looking at fig.5 again it is clear that the melody from phrase to phrase ascends with a second (m.16 and m.20) while harmonically we are in a descending third progression. It fits however: m.16 is A major, the IV of E major and m.20 is B major, the V of E major. One should realise that three times a (diatonic) third down is the same as a second up. Of course there is the difference of one octave but that is resolved by the octave jump in mm.19-20. So in fact the first two phrases could be notated as an A2(-3/-3/-3) sequence. Look here for some explanation on the notation of sequences.

Now the third phrase (mm.24-27) is a surprise and not a surprise. It is not a surprise because the descending third progression just continues as before with the exception of the last beat of m.27. Also the octave jump is there (mm.23-24) which is now a c-sharp minor chord (the vi of E major). Therefore also the sequence of the phrases continues: the IV (m.16), the V (m.20) and the vi (m.24) of E major.

The surprise however is the modulation Schumann makes in the third phrase: to g-sharp minor. The pivot is in m.24 where the vi of E major in retrospect should be spelled as the iv of g-sharp minor. The descending third progression stays diatonic, but now in g-sharp minor.

Notice that the chord progression in the third phrase is nearly the same as in the first phrase, be it that the chords have different qualities as the first phrase is in a major and the third in a minor key.

There are two differences. The first one being the third beat of m.26 (fig.5). It is a tonic chord (g-sharp minor) as the start of the (deceptive) cadence. I interpreted the E natural in m.18 as a passing note. The third beat of m.18 could however be spelled as IV in E major. And the second difference is of course the deceptive resolution on the third beat of m.27.

The motivic material is different in the third phrase. The imitation in the voices has stopped and there is a fragmentation of the theme. That is the reason that segment 1 could be interpreted as a 4+4+4 sentence-like structure. Look here for my post on the concept of sentence. In the piano quartet Schumann also plays with the form of the sentence. Find my post on the analysis of the first movement of the piano quartet here.

The modulation to g-sharp minor

One question remains to be answered: why the modulation to g-sharp minor in the third phrase?

To answer that an understanding of the harmonic context is helpful. As has been shown the first segment starts in A major but immediately modulates to a sequence in E major. The second segment of the Transition (mm.28-35, fig.8) is the main theme in B major, the dominant of the key we are headed for in the second tonal area (STA, table 1). This will be shown shortly. In between are these four measures (mm.24-27) in g-sharp minor, which are also part of the harmonically descending third sequence.

When looking closely at the mm.27-28 it is clear what construction Schumann did choose. Measure 27 ends on an E major chord which is suspended in m.28. It is a pivot chord and in retrospect turns out to be the IV of B major. Then the C-sharp is added on the third beat and it becomes a ii65 in B major, completely in line with m.8 (fig.3). (There it is a ii65 in A major of course.) Could Schumann have ended on an E major chord in a different (less exotic) way, then to modulate to g-sharp minor?

Well yes! He could have stayed in E major for example. Figure 7 shows what this harmonically would have looked like. So no modulation to g-sharp minor and nevertheless still (or perhaps even more easily) fitting in the diatonically descending third progression.

fig.7 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, mm.16-28, harmonic alternative

But … first of all the ending in m.27 with the vii0 – I progression (fig.7) is much more of a closure then the deceptive cadence in Schumann’s version which implicates (or makes the experienced listener expect) some kind of resolution or progression to stability.[8]See Leonard B. Meyer, Explaining Music: Essays and Explorations (Berkeley [etc.]: University of California Press, 1973), 115 fn 1, for an explanation on the difference between implication and expectation.

So Schumann’s version is much more open, invites as it were the next segment (2) and makes the transition smooth. As we are in the beginning of the Transition this tonal instability is quite comprehensible.

Secondly – and this refers again to Schumann’s metaphorical interpretation of the tonic triad – when we consider the Transition from the perspective of the key it is transitioning to (E major), we find the following harmonic progression:

E major – g-sharp minor – B major [- C major] – B major

How happy we are to find again the tonic (I) – mediant (iii) – dominant (V) progression which occurs strikingly often in Schumann’s chamber music. Look here for the quotes of Schumann which reflect his thoughts on this metaphor. The C major excursion will be explained in the paragraph on the third segment of the Transition.

I think these two arguments could explain the choice for the modulation to g-sharp minor.

The Transition: Segment 2

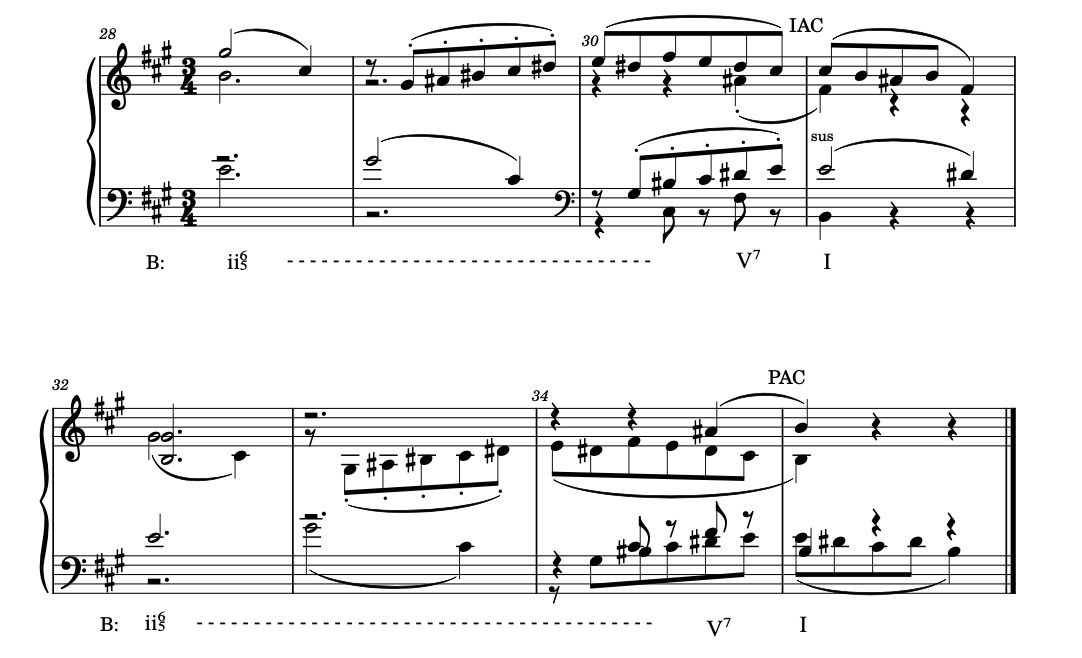

Figure 8 shows the score of the second segment. As mentioned it is the main theme in B major. Schumann however added an imitation in the viola (m.29 and m.33). The harmonic structure is the same as in the first tonal area (FTA, fig.3); it is again a parallel period and contains no new melodic material.

fig.8 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, mm.28-35

The Transition: Segment 3

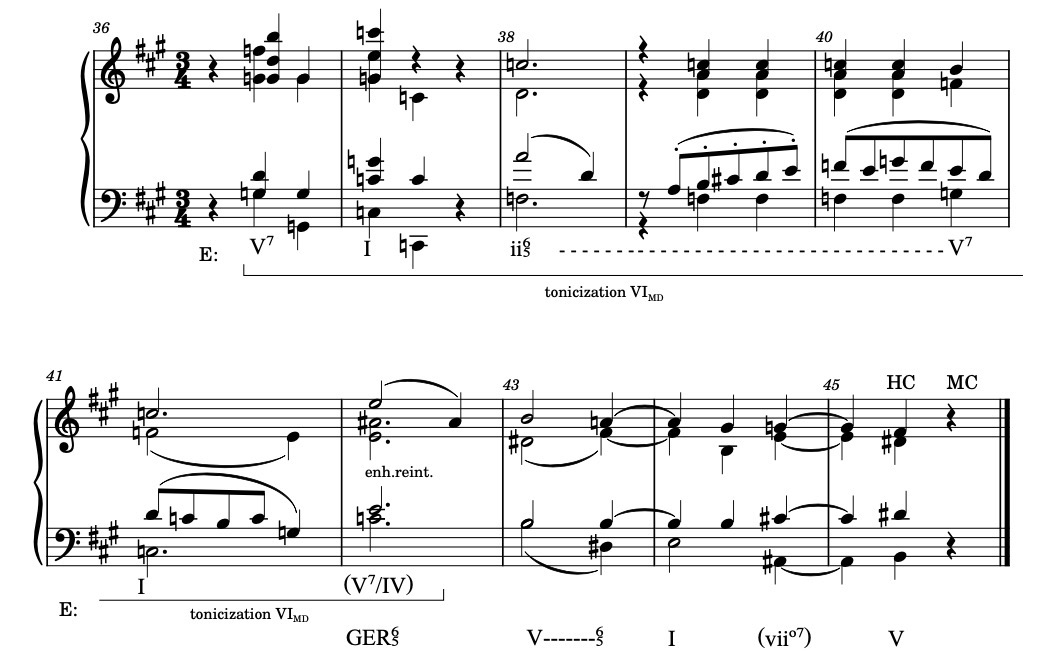

The third segment (mm.36-45) contains another surprise. As shown in fig.9 the measures 36-37 make a rather sudden modulation to C major by way of the applied dominant (m.36).

fig.9 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, mm.36-45

The antecedent of the main theme is repeated once more, this time in C major. It does not end with an imperfect authentic cadence (IAC) as in m.11 (fig.3) and in m.31 (fig.8), but with a C dominant seventh chord which should however be reinterpreted as an augmented sixth chord (GER65) in E major. Schumann already wrote an A-sharp instead of a B-flat. As explained elsewhere the GER65 has two leading tones to the dominant. In this case these are the A-sharp in the second and first violin and the C natural in the cello. The chord functions as a predominant and indeed the dominant does follow in m.43.

Keep in mind that the second tonal area (STA) is in E major (the dominant of A major), so the B major of the second segment can easily be interpreted as the dominant of E major. As we are quite close to the STA, I chose to give the C major phrase its function in relation to E major: it is the VIMD of E major and functions as a predominant. It is the lowered sixth scale degree made a major chord by also lowering the third scale degree of E major: a G natural in stead of a G-sharp. Therefore the phrase mm.36-42 has been made a tonicization of VIMD. (See my post General notes on analysis for a brief explanation of Moll-Dur and of tonicization.)

In mm.42-44 there is again the a2 motive (fig.4). It all ends with a half cadence (HC) in E major, a perfect introduction to the second tonal area (STA). Before that starts there is a genuine medial caesura (MC) on the third beat of m.45. A brief explanation of the MC can also be found in General notes on analysis.

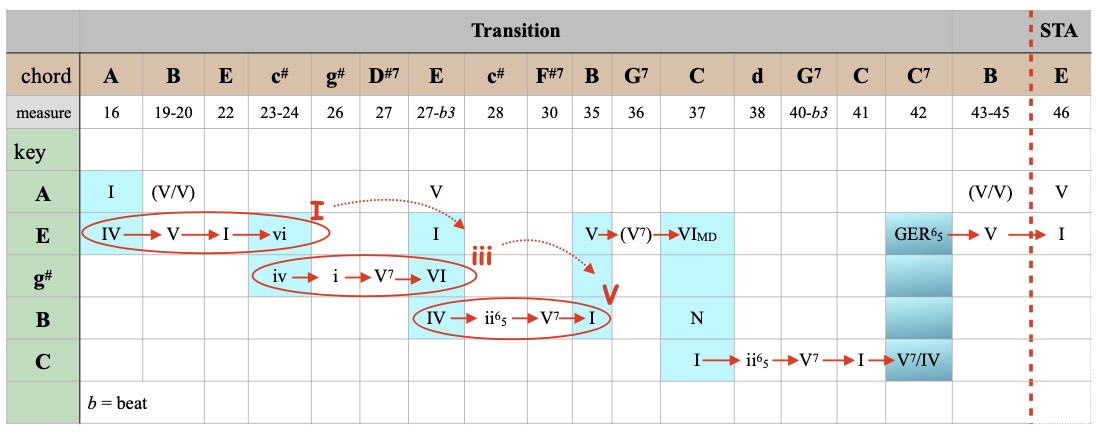

The Transition: overview of the harmonic progression

The diagram in figure 10 again tries to explain how you can look at different levels of analysis at the chord progression in a certain section of a piece. In this case these levels are:

- the level of the exposition (and in fact of the Allegro molto moderato as a whole)

- the level of the various components within the exposition (FTA, Transition, STA, Closing Section)

- the level of segments within these components (for instance a cadential area).

fig.10 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, levels of analysis in the transition

The keys as mentioned in the first column of the diagram correspond to these levels as follows:

- A major, as the key of the Allegro molto moderato, and the first tonal area (FTA)

- E major as the key of the component second tonal area (STA)

- B major, g-sharp minor and C major as segments or phrases within the Transition; B major also as the key of the cadential area within the Transition (mm.43-45)

A selection of the chords as encountered in the transition are shown in the second row and the third row gives the measure(s) in which they are found. The cyan coloured cells in a column mean that a chord can belong to more than one of the mentioned keys; they can be used as a pivot chord to go from one key to another. The partial cyan coloured columns are a sort of elevator to go from one key to another. The partial blue column with gradient implies also a pivot chord but one that needs an enharmonic reinterpretation. It occurs in fig.10 in m.42: the C dominant seventh chord is reinterpreted as a GER65 in E major. The B-flat must be spelled as an A-sharp. The red arrows, together with the elevators, lead you through the harmonic progression.

Looking at the overview in fig.10 is becomes clear that the Transition is thought of from the key of E major. The first two phrases of the first segment (mm.16-23) are a descending third progression diatonically in E major. The third phrase of the first segment (mm.24-27) is the same progression but in g-sharp minor. In fig.10 this is shown as the red I and iii. By way of the deceptive cadence in m.27 and the pivotal change to the IV of B major on the third beat of m.27 the main theme returns in B major (segment 2). So again Schumann uses a I – iii – V progression.

As the second segment ends with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in mm.34-35 (fig.8), this is not a good transition to the second theme; it is too much of a closure. So Schumann adds a predominant – dominant progression which ends with a half cadence (HC) in m.45 and provides for an open ended invitation for the second theme in E major. That is the function of the third segment. The predominant gets a special flavour as it is the VIMD of E major. Notice that the chord progression used for the occurrences of the main theme is exactly the same as the one used in the first tonal area (FTA, fig.3).

The subordinate theme or Second Tonal Area (STA)

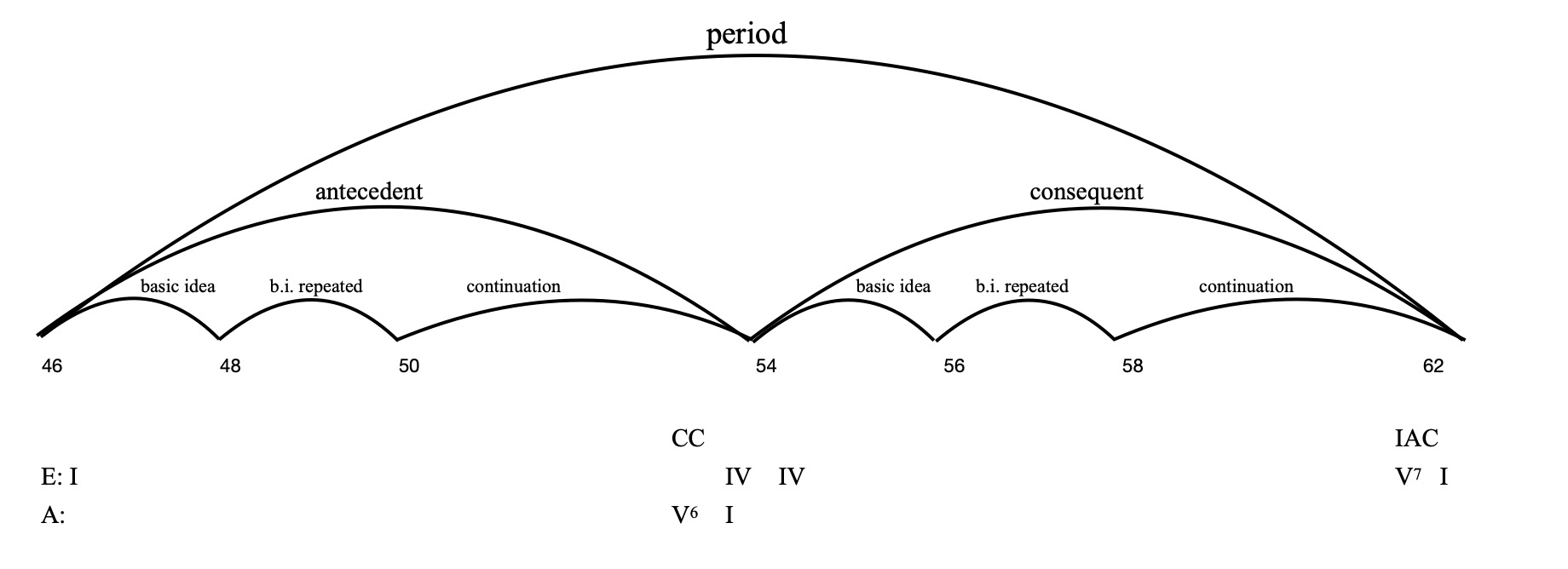

Periods

As opposed to the first tonal area (FTA) or main theme, the subordinate theme or second tonal area (STA) is quite extensive, consisting of 44 measures. A downloadable PDF of the complete STA with my annotations can be found here. Schumann modelled this as a repeated parallel period of which both the antecedent and the consequent consist of a sentence. My posts on the sentence and the period explain these concepts.

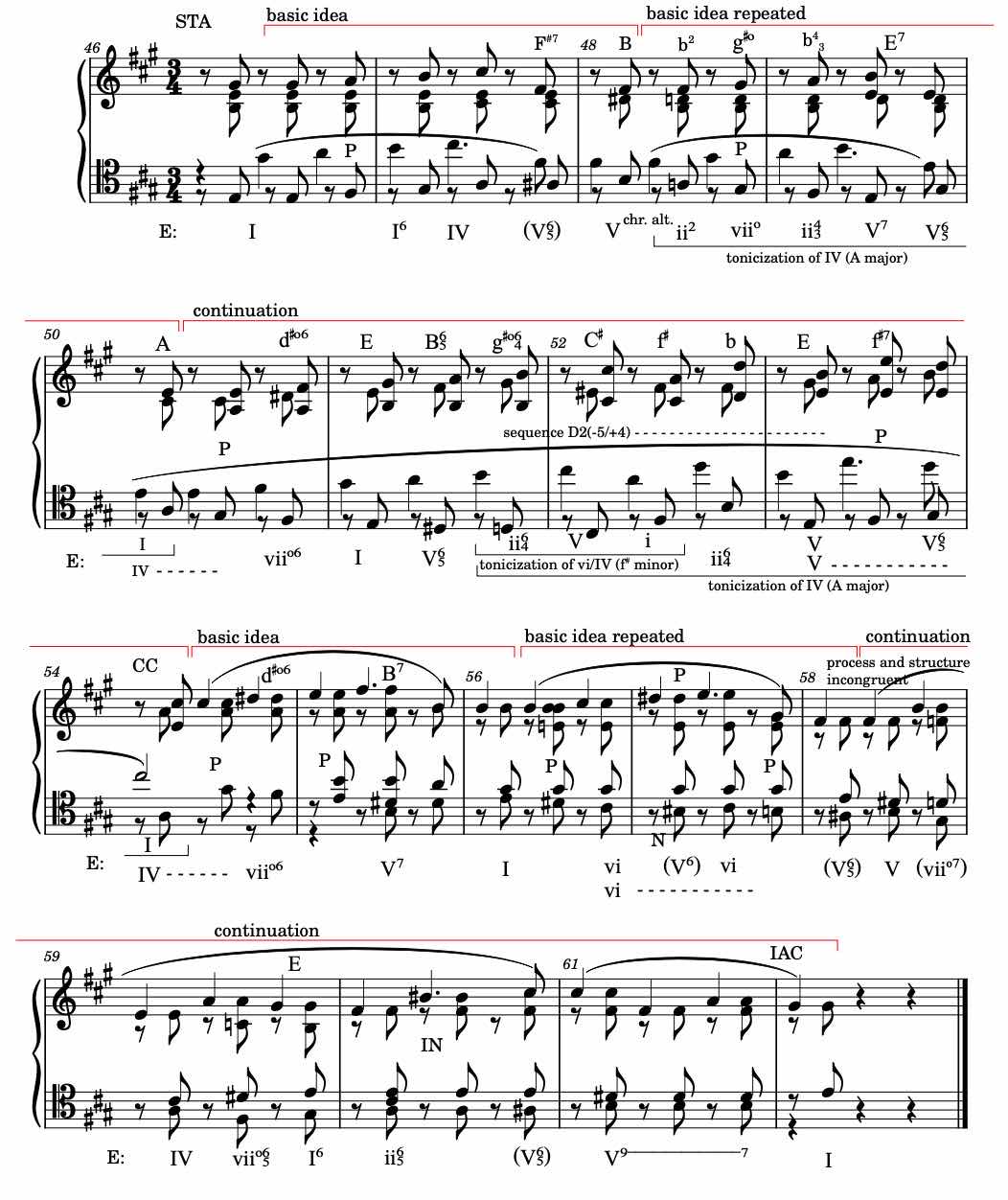

fig.11 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, mm.46-62: parallel period with nested sentence

To keep the overview fig.11 shows a diagram of the first occurrence of the period (mm.46 second beat-62 first beat). This period is repeated in its entirety in mm.62 second beat-78 first beat, albeit that from the second beat of m.77, things continue differently.

Figure 11 shows the harmonic progression in outline only. The cadence at the end of the antecedent (CC = contrapuntal cadence) is weaker then the cadence at end of the consequent (IAC = imperfect authentic cadence), as befits a decent period. Moreover the CC is in A major and the IAC is in E major (the key of the second tonal area). In fact, this is another exception to the classification of periods as found in my post on the concept of period. It is an exception because the only cadences considered at the end of the antecedent are the half cadence (HC) and the authentic cadence (AC) but no CC is mentioned. It resembles however possibility 11 of parallel periods in table 1 of the mentioned post.

First period (mm.46-62)

Now keep fig.11 in mind as we dive deeper into the first period. Figure 12 shows the piano score. Notice that I used the tenor clef for the second staff in the system as the cello plays the melody in a rather high register whereas the viola takes the roll of bass.

fig.12 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, mm.46-62

Let’s this time start with the rhythmic aspect as this is famous and notorious, especially among those who play. The fact that the accompaniment is a syncopated figure is not too complicated but the fact that it starts before the melody (second half of the first beat of m.46) makes it tricky. It gives the whole passage an unbalanced character and the melody seems to limp behind the beat. This applies to the entire period.

Form and motives

As mentioned before Schumann modelled the antecedent and the consequent of the period as a sentence. How to decide on this? As shown in my post on the sentence, the structure follows mainly from the melodic/motivic structure. It is clear that the motive of the first two bars w1 (m.46 second beat to m.48 first beat) is immediately repeated in mm.48-50, w2. Then a four bar phrase follows with a more elaborate extension and this fits perfectly in the concept of the sentence. The 1:1:2 proportion is respected and the absolute length is 2+2+4 bars. Figure 13 shows the motives of this sentence.

fig.13 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, theme and motives up to the first period of the STA

It is clear that each entrance of the motive is one second lower then its predecessor. So we are looking at a melodic sequence; melodic because the harmonicization is quite irregular as we will shortly see. The end of the w1 motive is again a fall of a fifth so it resembles very much the a motive and is therefore called a4. The end of the x1 phrase is a new version of the v motive (v3). The d1 motive is a special case. Its similarity with the a4 and a5 motives is evident, especially when looking at the rhythm. They are put in the a motive family because of the falling fifth (or sixth). The d1 motive does not have the falling interval nor the rhythm of the original a1 motive. Therefore I did not put it in the a family of motives but gave it one of its own. We will encounter it later (in the internal extension of the STA).

The second sentence follows the same melodic pattern and therefore it can be seen as the consequent of a parallel period. In the consequent the basic idea and the repetition of the basic idea use the w1 motive shifted up one fourth (respectively w3 and w4). At the end of the repetition of the basic idea the preparations for the cadence begin. There is not a fall of a fifth but of a sixth (motive a5). The melody in the continuation of this sentence is completely adjusted to fit the IV – ii – V – I cadential progression (mm.58-62). Noteworthy is the B-sharp in m.60; it is the incomplete neighbour note (IN) to the C-sharp to come, creating a nice tension. The F-sharp and the A natural in m.61 are in fact double neighbour notes of the G-sharp coming up.

Overseeing the motivic landscape we find again a high coherence. Schumann is very efficient with his motivic material and reuses it time and time again although this is not immediately apparent on first hearing (at least for me).

Harmonic analysis

Antecedent (mm.46-54)

The basic idea of the first sentence starts in E major, the key of the second tonal area (STA). It advances from the tonic to the dominant. The basic idea is repeated in A major, one fourth up, as opposed to the motive, which descends by one second. If this were to be a D2(-5/+4) sequence – corresponding to the melodic sequence – the key should have been D major. Schumann however chose otherwise and thus created tension between the harmonic and melodic progression.

The progression in the repetition of the basic idea is a cadential one. Notice how Schumann made the modulation to A major: in m.48 he makes a chromatic alteration in the B major chord to make it b minor which functions as a predominant ii in A major. The common tones are the B natural and the F-sharp.

I modelled this part as a tonicization of IV (A major) within the E major context, despite the fact that the cadence in A major is pretty strong. Indeed, the A major orientation remains quite strong in the continuation also, so I can imagine that an analysis in A major is also very conceivable. I chose however to stay in E major to keep a close connection to the overall harmonic structure. It is clear however that the ambiguity of key which also occurred in the first and second string quartet is present again.

When looking from the perspective of E major at the continuation in the antecedent (mm.50-54), it starts with a diatonic descending bass (m.50 2nd beat – m.51 2nd beat) in that key. It is an opposite movement to the melody in the cello. It is harmonized with the tonic E major and its dominant.

Then follows a vi – ii – V – I progression in A major, again modelled as a tonicization of IV of E major. Within that Schumann elaborates on the vi (f-sharp minor, mm.51-52) and therefore this is also modelled as a tonicization (m.51 3rd beat – m.52 2nd beat), within the tonicization of the IV. Again Schumann uses a chromatic alteration to progress from the B major seventh chord to the g-sharp diminished chord (m.51). Here the only common tone is the B natural.

Consequent (mm.54-62)

In the basic idea of the consequent the key of E major has definitely been found again. It is a cadential IV – V – I progression. The repetition of the basic idea is harmonised with the vi (c-sharp minor). The first beat of m.58 is the applied dominant of the dominant. On the second beat of that measure the continuation starts with the dominant after which a cadential progression follows, ending in an imperfect authentic cadence (IAC). From the second beat of m.59 there is an irregular ascending bass line with chords in first inversion. It is a Fauxbourdon like progression.

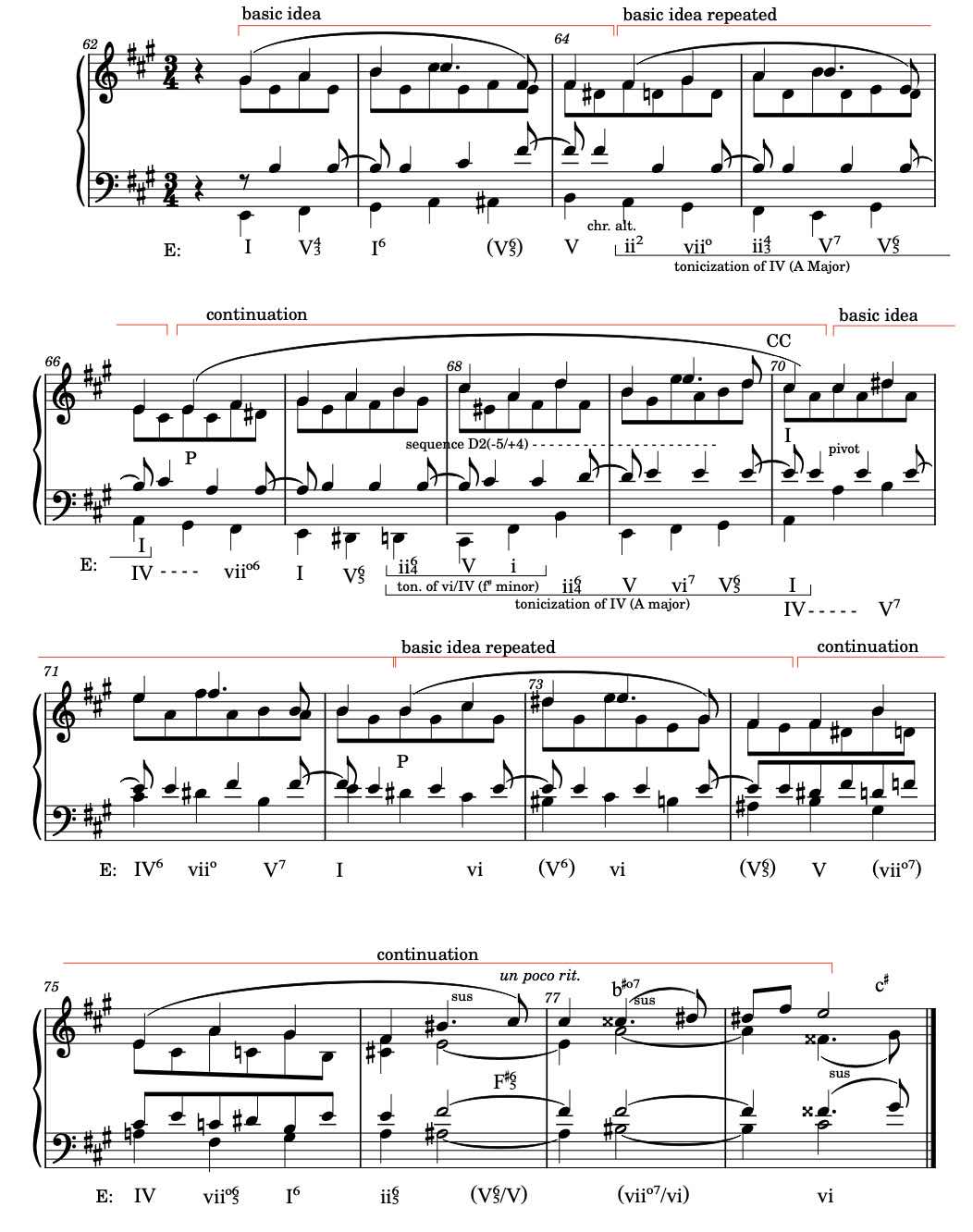

Second period (mm.62-78)

The second period is very similar to the first. Therefore I will only discuss the differences. The second period has the same structure as the first so fig.11 applies. Figure 14 shows the piano score of the second period.

fig.14 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, mm.62-78

Form and motives

The same motives are used as in the first period, in this case it is the first violin that plays them all. A contrapuntal bass line is played by the cello starting in parallel thirds with the melody. The second violin is now playing running eighth notes in the accompaniment and the only voice that plays the syncopes is the viola. Nevertheless the effect is nearly the same as the first eighth note on the beat of the second violin doubles the note in the melody, so the second one (the syncopation) comes out well.

Harmonic analysis [H5]

The harmonies used in the second period are the same as in the first be it that here and there a V is replaced by a vii0 and vice versa. The only difference between these chords being the presence or not of the root of the dominant chord. No significant changes except for one: there is no cadence at the end of the second period.

From the second beat of m.77 (comparable to m.61 in the first period, fig.12), things take a different turn. The F-sharp dominant seventh chord in m.76 third beat is the last chord that is the same as the corresponding chord in the first period (m.60, fig.12). In the first period the F-sharp dominant seventh chord is followed by a B dominant nine/seven chord which then leads to the tonic E major. So the function of the F-sharp dominant seventh chord is clear: it is the applied dominant of the dominant.

In the second period the F-sharp dominant seventh chord is followed by a b-sharp diminished chord (m.77, fig.14) after a suspension with a passing C double-sharp in the first violin. Schumann did this by a chromatic alteration: B-sharp instead of a B natural and a C double-sharp instead of a C sharp. The last one resolves to the D-sharp on the second half of the third beat. The b-sharp diminished chord functions as an applied diminished seventh chord for the vi (c-sharp minor) to come (m.78 second beat). We are still talking E major, the key of the second tonal area (STA). How this proceeds can be found in the section on the Internal extension of the overall period.

Periods reviewed

After reviewing the two periods it comes to mind that these periods taken together can be seen as yet another period on a higher level. The form then becomes:

Segment

overall period

overall antecedent = period 1

antecedent 1

consequent 1

overall consequent = period 2

antecedent 2

consequent 2

Measures

46sb – 78fb

46sb – 62fb

46sb – 54fb

54sb – 62fb

62sb – 78fb

62sb – 70fb

70sb – 78fb

Table 3: layout of the periods of the STA [fb=first beat; sb=second beat]

Both antecedent 1 & 2 and consequent 1 & 2 are sentences as shown in fig.11 for period 1. The same holds for period 2. I am sure you are able to draw the diagram of this structure yourself now.

As already has been mentioned, the second period does not end with a cadence which is not comme il faut. The overall consequent of a decent period should end (consequent 2) with a stronger cadence then the overall antecedent (consequent 1). Remember that the overall antecedent/consequent 1 ended with an IAC (mm.61-62, fig.12). Schumann uses an internal extension to still achieve a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in E major. This is the subject of the next section.

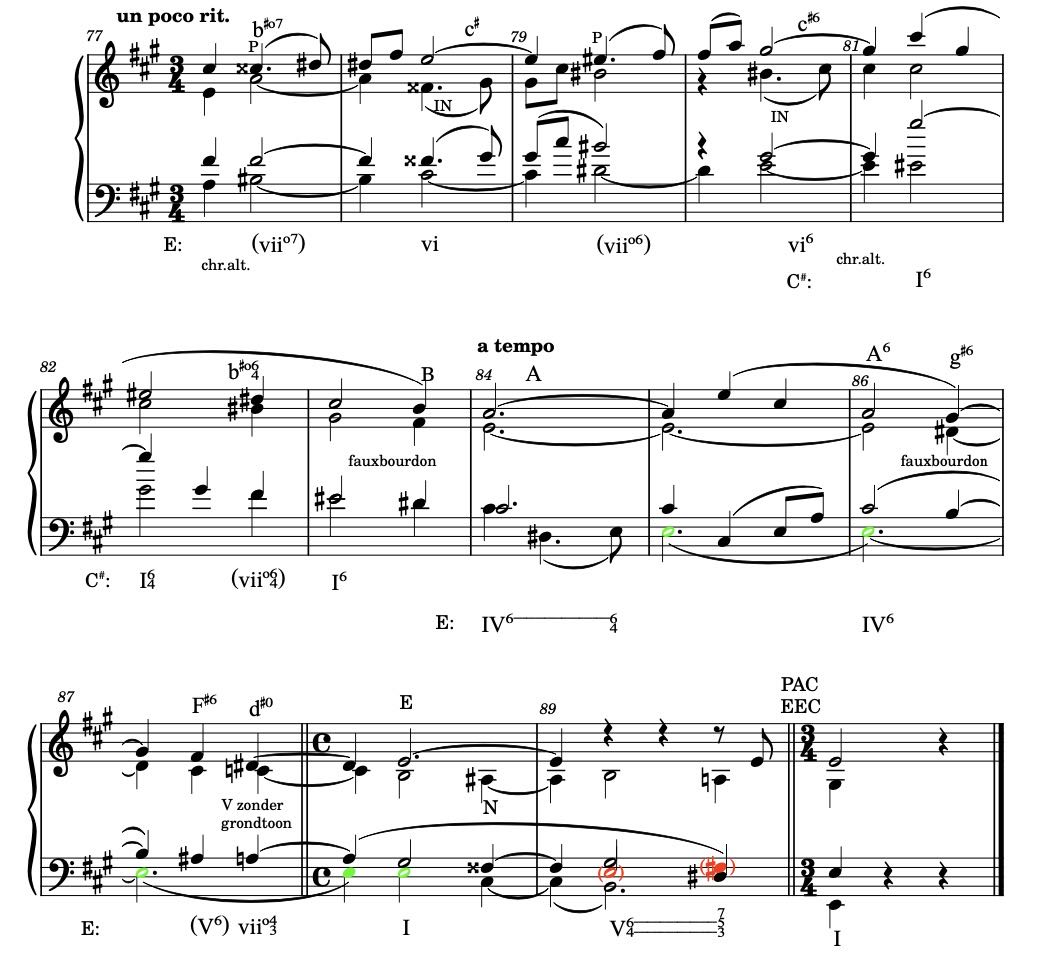

Internal extension of the overall period

When counting measures the continuation of the sentence within the consequent of the second period, starting in mm.74 second beat, should end on the first beat of m.78 (four bars). However, we already saw that things start to diverge from the second beat of m. 77. So the three beats from this point to m.78 first beat are in fact a transition or overlap between the end of the overall period and the coming phrase. Therefore fig.15 includes m.77 to show the connection.

fig.15 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, mm.77-90

Now why call this part an internal extension of the overall period? The main reason is that the second tonal area (STA) is waiting for a proper closure or resolution. This has neither melodically nor harmonically been found at the end of consequent 2, coinciding with the end of the overall period, mm.77-78.

A strong indicator for a closure of a phrase is the occurrence of a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in the prevailing key, E major, the key of the STA. The first PAC in E major so far is found in mm.89-90.

Melodically the phrase continues with the motive of m.76 (motive d1, also found in m.60 in the first period, fig.12). So melodically no break but a continuation. Therefore these measures belong to the STA, but they are an extension as they do not fit in the regular structure of the period(s). The adjective internal is added because the extension is before the cadence that closes the STA.

What master plan did Schumann have in mind for this internal extension? My hypothesis is as follows:

The harmonic side of the coin

The harmonic progression in outline in mm.77-88 first beat, can be represented as follows:

c# (relative minor of E) ==> C# (parallel major) ==> (Fauxbourdon) ==> A ==> (Fauxbourdon) ==> F# ==> d#07 ==> E

Measures 88-90 first beat are a (full) cadential progression in E major resulting in the PAC and at the same time the Essential Expositional Closure (EEC).[9]Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 18.

Measure 90 first beat is an overlap between the extension and the Closing Section. Notice that Schumann uses incomplete chords in m.89. I added the missing notes between brackets in red to be able to identify the chords being used.

Here is the harmonic progression again with roman numerals relative to E major:

E: c# (vi) ==> C# (VI) ==> A (IV) ==> F# (V/V)==> d#07 (vii0) ==> E (I)

Looking at them one by one the c# minor harmony extends from mm.77-81 first beat. The two occurrences (in m.78 and m.80 respectively) are preceded by their applied diminished seventh and dominant chords, also functioning as passing chords. c# minor is the vi of E major and the relative minor of that key.

Then the surprise in C# major follows (m.81, second beat), the parallel major of c# minor. It is a form of modal mixture. The clouds break open and the sun comes out, though cautiously because it is in pianissimo. Only two bars later (m.84) follows an A major chord that does not fit in C# major. The B major chord on the third beat of m.83 is foreign to C# major also. Schumann uses a Fauxbourdon like construction (a series of chords in first inversion) to come down from seven to four sharps. This occurs in mm.83-84.

After a suspension on IV6 in mm.84-85 the Fauxbourdon is continued to lead to F# major on the second beat of m.87 and then we are home. The F# major is the dominant of the dominant of E major. Schumann uses the dominant version without the root which is a vii07 (in second inversion, the d# diminished chord, third beat of m.87) which leads to the I on the second beat of m.88.

Looking at the passage with a birds eye view the progression can be reduced to:

E: vi/VI – IV – vii0 – I

in fact an extended cadential progression that is confirmed with the PAC in mm.88-90.

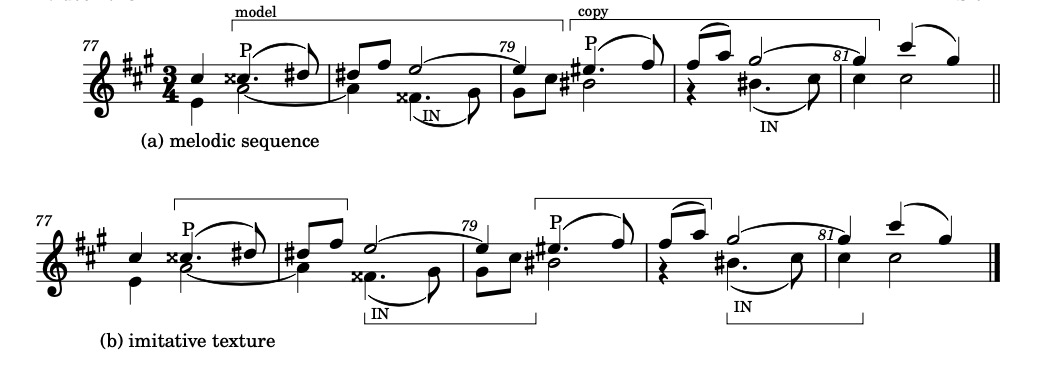

The melodic/motivic side of the coin

When we look melodically at the extension, fig.16 may offer some insight.

fig.16 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, mm.77-81 melodic analysis

Schumann continues using the d1 motive (fig.13) in mm.77-81 first beat, in a melodic sequence. The first occurrence is labeled model and the repetition a third higher copy (fig.16a). Inside there is an imitative texture as the second violin repeats the d1 motive in the second half of the sequence unit, shown in fig.16b. Taking into account the harmonisation one can think of mm.77-81 as an upward arpeggio of c# minor.

In the same manner mm.81 second beat – 83 first two beats, can be seen as a downward arpeggio of C# major. The entrance of the first violin in m.81 is imitated in the cello in m.82. What follows of m.84 onward is mainly a cadential progression with some fragments of previous motives in the cello, viola and first violin. The rhythmic structure there is reminiscent of the ending of the Transition (mm.42-45, fig.9).

Closing Section

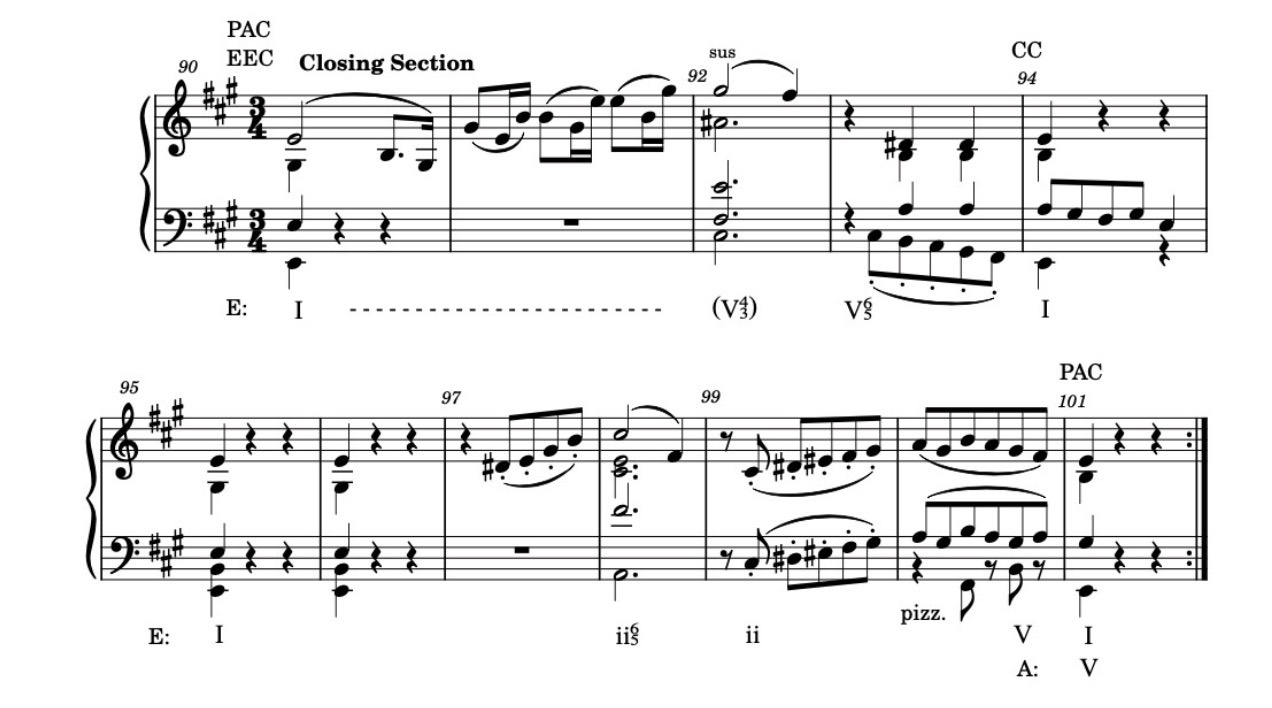

Figure 17 shows the piano score of the last part of the Exposition: the Closing Section.

fig.17 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.3, i, mm.90-101

In the string quartets op.41 no.1 and 2 the Closing Section consists of a series of codettas of 4 bars each. This Closing section has a somewhat irregular structure. It does consist of two phrases which confirm the key of the second tonal area: E major. The first one ends with a contrapuntal cadence (CC) in mm.93-94; the second one with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in that key.

To start with the last phrase (mm.97-101): this is clearly the consequent of the main theme in E major (fig.3) with one bar upbeat. The second and third bar of the theme contain a slight variation as the viola doubles the first violin.

The first part of the first phrase is a connecting E major triad (m.90 third beat – m.91), followed by a variation of the main theme. The first bar (m.92) does not contain the falling fifth, but only a falling second which has a more open character. The harmony is also different: the dominant of the dominant which also has a predominant function and leads to a dominant-tonic ending, be it in a weak form. Therefore bar two and three of the main theme have been compressed into one bar only (m.93). The key is reinforced by two statements of the E major chord surrounded by a rest of two quarter notes. It reminds us of the rests in the slow introduction: whatever hypotheses the listener may consider about the things to come, there is just another confirmation of E major, but now completely in the world of the opening theme.

This concludes the analysis of the exposition of Schumann’s third string quartet.

Notes

| ↩1 | John Daverio, Robert Schumann: Herald of a “New Poetic Age” (New York etc.: Oxford University Press, 1997). |

|---|---|

| ↩2 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 251. |

| ↩3 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 242. |

| ↩4 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 243. |

| ↩5 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 244. |

| ↩6 | I am indebted to Menno Dekker who kindly called my attention to this very comparable opening by Beethoven. |

| ↩7 | For a great introduction to stability and closure see: chapter IV Principles of Pattern Perception: Completion and Closure in Leonard B. Meyer, Emotion and Meaning in Music (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1962). |

| ↩8 | See Leonard B. Meyer, Explaining Music: Essays and Explorations (Berkeley [etc.]: University of California Press, 1973), 115 fn 1, for an explanation on the difference between implication and expectation. |

| ↩9 | Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 18. |

Recent Comments