Schumann string quartets: the comparison

Last updated on December 7th, 2024 at 01:29 am

Table of contents

Introduction

This post is about a comparison of the expositions of the first movements of the string quartets written by Schumann in June and July of the year 1842 (by clicking on the string quartet you can access my posts on the analysis of the exposition):

String quartet in a minor, op. 41 no. 1 (composed: beginning of June 1842)

I Introduzione: Andante espressivo – Allegro

String quartet in F major, op. 41 no. 2 (composed: middle of June 1842)

I Allegro vivace

String quartet in A major, op. 41 no. 3 (composed: 8 -22 July 1842)

I Andante espressivo – Allegro molto moderato

This is the fourth and last post in this mini series and deals the comparison of the quartets. The reason why I started this series can be found in the introduction of either one of the posts on the string quartets.

I want to thank Menno Dekker – my former professor at the conservatory of Amsterdam – for the very useful discussions I have had with him about this analysis. I am very grateful to have the opportunity to drink in upon his incredible knowledge of music theory.

Historical context

In the beginning of 1842 Schumann had quite a difficult time, as a matter of fact it was “the first major crisis of Schumann’s married life”. Clara was on a concert tour in northern Germany and Robert accompanied her. After one of the concerts (in Oldenburg on the 25th of February) Schumann was not invited for the after concert party. Clara decided to attend on her own and Robert was furious and returned to Leipzig alone. In the weeks to follow – spent alone in Leipzig – “Schumann occupied himself with exercises in counterpoint and fugue”.[1]John Daverio, Robert Schumann: Herald of a “New Poetic Age” (New York etc.: Oxford University Press, 1997), 242-244. The strings quartets are dedicated to Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, a good friend of Schumann.

Practical information

In this text a lot of references are made to the score of the string quartets. This is done by means of an identification of the string quartet and the measure number (always within the first movement). Ideally you have the scores with measure numbers at your disposal. The scores can easily be downloaded from IMSLP.

In general notes on analysis you can find some remarks on abbreviations, notation and concepts. Some books that I have been consulting can be found in consulted literature. At least all references made to literature in the notes should relate to entries in the consulted literature. The music examples are made in Musescore 4.

Sonata form terminology

The first movements of the string quartets are all written in the sonata form. Entire books have been written about the sonata form that contain a wealth of information on this concept. Here I am only concerned with the terminology being used. Any self-respecting author creates her/his own names for the various components of the sonata form. Usually there is an agreement on the names of the high level parts:

exposition – development – recapitulation

The terminology on the next (lower) level is more diverse. The sonata form is characterised by the statement of an opening theme in the main or home key. What follows (usually after a component called the Transition) is a contrasting section that differs always in the key being used and possibly also in the melodic/motivic material. These two components of the exposition boast a wide variety of naming. Table 1 provides some of the designations that can be found in the recent literature.

opening theme

contrasting section

Laitz[2]Steven G. Laitz, The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis and Listening (4th Ed (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2016), Chapter 27: Sonata form.

First tonal area (FTA)

Second tonal area (STA)

Caplin[3]William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998), Chapter 13: Sonata form.

Main Theme

Subordinate Theme

Hepokoski & Darcy[4]Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), Chapter 2: Sonata form as a whole.

Primary theme/idea (P)

Secondary theme zone (S)

Table 1: some naming of the two theme or key areas in the sonata form

In what follows I will use the terminology proposed by Steven Laitz, mainly driven by the fact that the exposition of a sonata form must have an area that is in another key than the home key, but the thematic/motivic material need not be different from the first presented main or primary theme.

For the two other components of the exposition, the Transition (Tr) and the Closing Section or Zone (CS), authors generally use more or less the same designation.

Notational convention for major and minor keys

As for a notational convention of major and minor keys: I will use capitals for major keys and lower-case letters for minor keys. For major keys I will often add the word major and for minor keys the word minor, but in music examples and diagrams the words major and minor will in general be omitted. So B major or B for B major and b minor or just b for b minor.

Most suitable devices

Finally it must be mentioned that although automatic adjustments are made to view these posts on tablets as well as mobile phones, they can best be accessed on a computer/laptop. The reason being that there are various tables and lists (like abbreviations) of which the columns will appear one beneath the other (especially on a mobile phone). If that is the case the coherence will be lost.

The comparison of the string quartets

The comparison of the quartets will be based on the consideration of a number of aspects. First some overall characteristics will be examined like the keys being used, the length of the various components in the exposition and the form of these components. More specific characteristics are discussed next, including the reason for this comparison, the position of the articulation of the dominant.

Some global characteristics

In this section I will try to paint a rough picture of the quartets and the first aspect to look at are the keys being used by Schumann.

The keys being used

Table 2 gives an overview of the opus 41 string quartets.

String quartet

no 1 in a minor

no 2 in F major

no 3 in A major

Slow introduction

a minor

–

b minor (ii)

FTA

F major

F major

A major

STA

C major

C major

E major

Table 2: the main keys being used in the first movements of the string quartets

Comparing the keys of the first tonal area (FTA) and the contrasting second tonal area (STA) it is clear that Schumann’s choice is quite classical. The key of the STA is always the dominant of the key of the FTA, a practice of the classical style of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, for major keys.

There are two surprises however:

- the FTA of the first string quartet is not in the home key (a minor), but in its submediant (VI or F major); this has been addressed in the analysis of the first quartet. That makes the choice for C major for the STA logical, the dominant of the (major) key of the exposition.

- the key of the slow introduction of the third quartet is away from the home key (b minor versus A major) and poses the emphatic question mark as explained in the analysis of the third quartet.

The relative length of the various components of the exposition

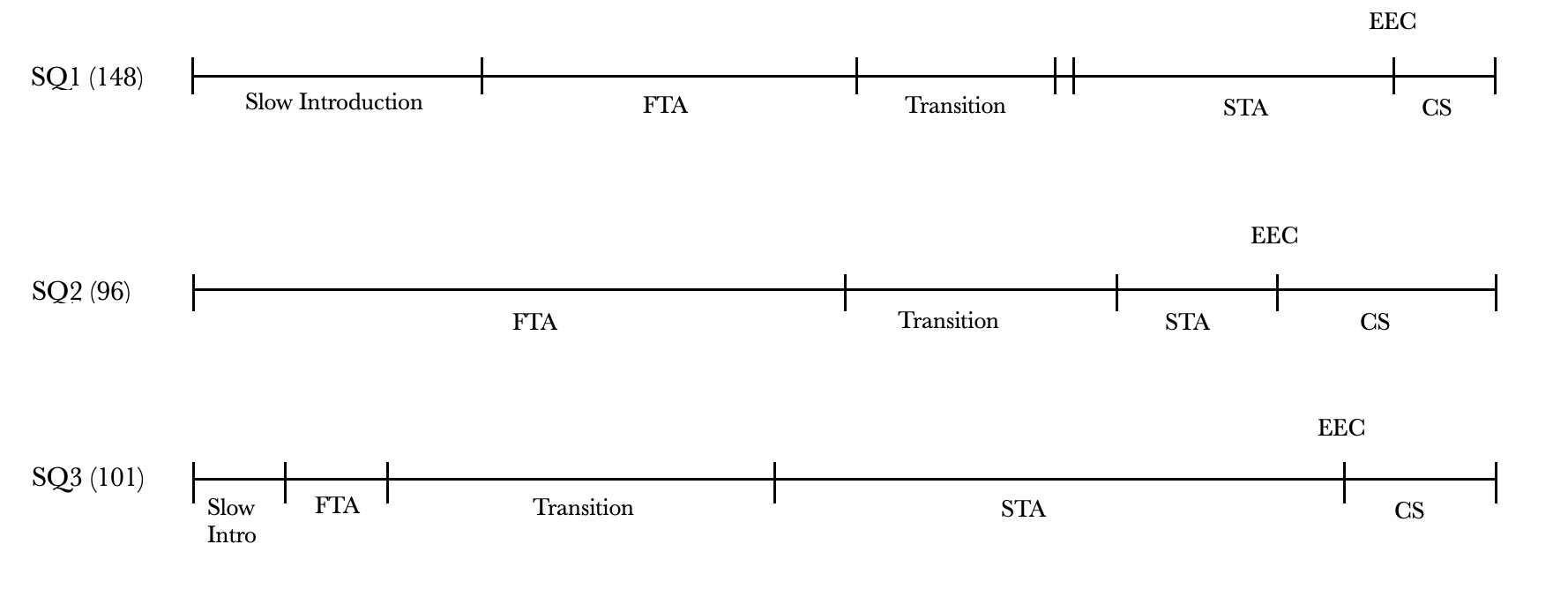

Secondly I examined the relative length of the various components of the expositions of the string quartets. Why? Because I set out to investigate the remark by John Daverio that the dominant is late articulated in the first (and last) movement of the second string quartet.[5]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 251. So what is late? Relative to the second tonal area (STA) or late in the exposition? Figure 1 shows the relative lengths of the components of the expositions.

fig.1: relative lengths of the components of the expositions of the string quartets

On the left you find the number of the string quartet and between brackets the number of measures of the exposition (including the slow introduction if present). It is immediately clear that the length of the FTA and STA in the second and third quartets is inversely proportional.

The FTA of the second string quartet is 48 measures and in fact half of the exposition. The STA of the second quartet is a twelve measure phrase or 12.5% of the exposition.

The FTA of the third string quartet is a simple eight measure period or 8.5% of the exposition. The STA of this quartet is the double or nested period of 32 bars followed by an extension of 12 bars, a total of 44 bars or 47% of the exposition.

When taking the combined lengths of the FTA and STA as percentage of the length of the exposition without the slow introduction then we see that this combined length in the second string quartet is 62% and in the third it is 55%, not too big a difference.

The first string quartet resides somewhere in the middle of these two. It is of course characterized by the long contrapuntal introduction of 33 bars, but the FTA and STA are about equal in length: 42 respectively 36 measures long. The combined length of these two make up for 69% of the exposition (i.e. without the slow introduction).

Schumann chose to give all the string quartets a Closing Section (CS), the length of which determines the relative position of the Essential Expositional Closure (EEC). The EEC roughly being the first perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in the key of the second tonal area (STA). As shown in fig.1 the CS of the second quartet is the longest (absolute (17 bars) and relative (18%)), placing the EEC relatively early.

The form of the components of the exposition

Table 3 gives an overview of the forms that Schumann used in the various components of the exposition. One can conclude that the structure of the quartets is quite classical. The FTA’s are well structured and in the first two quartets they share the same form (ternary). The STA’s are much looser in form and this fits in the theory of formal functions of the sonata form as presented in the book by Caplin on the Classical Style.[6]Caplin, Classical Form, 17-21. Only the third quartet has a tightly organized STA: it is the double period with an internal extension.

Component

FTA

Transition

STA

Closing section

SQ1

ternary (16+16+10)

fugato style+cadential

sequences+cadential

3 codettas

SQ2

ternary (16+16+16)

sentence/sequence/cadence

period+ext. or sentence like

2 codettas + cadential

SQ3

period (4+4)

sequence+period+cadential

double period+extension

2 irregular codettas

Table 3: forms being used in the various components of the expositions

The transitions are – like the STA’s – looser in form but they all contain thematic/motivic material from the first tonal area (FTA) and can therefore be called Dependent Transitions (DTr).[7]Laitz, The Complete Musician, 636. The Closing Sections (CS) also follow the classical rules and consist of several codettas be it that the CS of the last quartet is somewhat irregular.

Some more specific qualities

The articulation of the dominant

The remark by John Daverio concerning the articulation of the dominant in the second string quartet is the reason for this small series of four posts on the Schumann’s string quartets. When trying to say something about this the first question to be answered is: what is exactly meant by the articulation of the dominant?

First of all: why talk about the dominant? As table 2 shows all the second tonal areas (STA’s) are in the key of the dominant of the home key (of the exposition). So the question is when the key of the STA is articulated. Then remains the question what is meant by articulation. I think this means something like to experience or getting a clear feeling of the key of the dominant. It can not be translated with the occurrence of a full swing cadence in the dominant because that coincides almost always with the end of the subordinate theme. As such it would no longer be a distinctive criterion.

The second string quartet

Starting with the second string quartet it has been made clear in the post on this quartet that the transition ends on the dominant of the dominant (G major, m.68) but that the key of the start of the STA is not immediately clear. This key (C major) is only established in the full cadential progression in mm.78-80, ending with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in C major. Earlier there are allusions to C major in the form of two half cadences (HC, m.72 and m.76) but the first occurrence of a C major chord is only at the end of the second tonal area (m.78). In this respect it can be called late. Is it late in the exposition as a whole? I would say yes, because only the closing section remains to finish the exposition.

The first string quartet

In the first string quartet the STA starts with a four measure phrase in C major (mm.101-104). In m.101 the phrase starts with a chord in first inversion but nevertheless it is unmistakable C major. Here also the perfect authentic cadence (PAC) follows later at the end of the STA (mm.136-137). The difference with the second string quartet is that C major occurs immediately at the start of the STA (at 68% of the exposition) whereas in the second string quartet it appears near the end of the STA (at 81% of the exposition). Because of the relative lengths of the various components of the exposition the difference is only 13%.

The third string quartet

The second tonal area of the third string quartet immediately starts with the secondary theme zone in the dominant of the home key, E major (m.46). This is at 45% of the exposition, so here it is really much earlier than in the second string quartet. It is also earlier then in the first string quartet but that has to do with very short primary theme of the third quartet (only 8 measures). The rounding off of the STA with the PAC in E major is in the internal extension (mm.89-90) and because of the length of the STA this is much later.

Conclusion

As Daverio has noticed the articulation of the dominant is late in the exposition in the second string quartet. It has become clear that the position within the exposition is very dependent on the relative lengths of the components of the exposition. The articulation of the dominant is (in these three string quartets) to be found in the second tonal area (STA). If that is late in the exposition then the dominant will be found late too, irrespective of the place within the STA. This is illustrated by the small difference in relative position of the dominant in string quartets 1 and 2 which is also reinforced by the fact that the second quartet has the longer closing section (CS, fig.1), pushing the end of the STA backwards to the beginning of the exposition.

So perhaps it is more meaningful to talk about the position of the articulation of the dominant in relation to the STA. In these quartets then the difference is immediately clear: early in the first and third quartet and late in the second.

The triad metaphor

As has been repeatedly mentioned, Schumann came up with a metaphor for the time line of (music) history which he projected on the tonal triad. Find the quotes of Schumann himself on this subject here. Just as a quick reminder: the tonic stands for the good and inspiring past, the mediant for the mediocre recent past and present and the dominant for a future that is fresh and poetic and does not have the shortcomings of the present.

Before going into any detail we need to answer the question of what is exactly meant by this metaphor. Was Schumann just talking about the scale degrees 1, 3 and 5 or did he mean the harmonic progression I-iii-V in major and i-III-V in minor? I think the metaphor should be interpreted as the harmonic progressions because otherwise, in multiple-voice music (be it polyphonic or homophonic), it would be impossible to identify in a significant way these three scale degrees.

And the next question is that if the metaphor is interpreted as a harmonic progression, how special is that specific progression (I-iii-V in major or i-III-V in minor) in tonal music in that era?

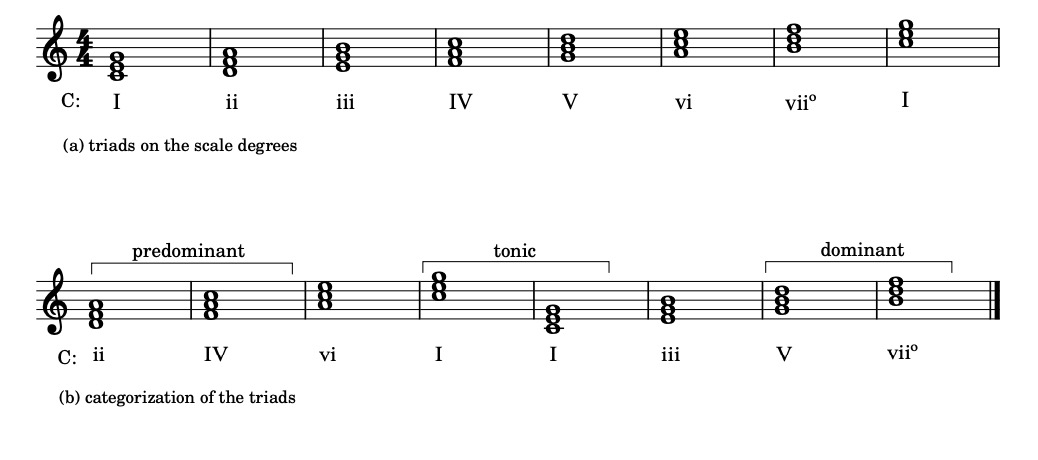

To get some sense of that let’s take a look at fig.2.

fig.2: triads on the scale degrees and a categorization of them

Figure 2a shows the triads on the scale degrees of a major scale (C major). Figure 2b shows a division in three categories: tonic, predominant and dominant. The predominant category consists of the triads on the second scale degree (ii) and on the fourth scale degree (IV); between them is a third relation and they have two common tones (the F natural and the A natural). The same holds for the triads on the fifth (V) and seventh (vii0) scale degrees and they form the dominant category, with common tones B natural and D natural.

There are left two ambiguous chords: the triads on the sixth (vi) and third (iii) scale degree. The vi has two tones in common with the tonic and two with the subdominant. This chord can in fact have two functions: a replacement of the tonic, which is for instance often used in a deceptive cadential progression, and as a predominant.

The iii also has two common tones with the tonic but whereas the tonic is part of the vi chord it is not part of the iii, even more so, iii contains the leading tone (the seventh scale degree) so the chord pulls strongly towards the dominant. When it is used to replace the tonic this is most often the tonic in first inversion (I6). It occurs for instance in an ascending arpeggiation of the tonic chord.[8]Laitz, The Complete Musician, 367-368.

In the classical style (roughly Haydn, Mozart and early Beethoven) the mediant in major keys (iii) was used but mostly to harmonise a melody note. It was not very often used as an (temporary) established key.

This is where Schumann makes a difference. In the light of his metaphor he uses the mediant (iii) fairly often and he emphasizes it by assuring that the listener experiences the mediant temporary as tonic. This fits in the definition of tonicization. So one might say that Schumann contributes to introducing a new harmonic progression which leads to the frequent use of mediant relations in the romantic style.

This holds mainly for major keys because in minor the progression to the (major) mediant (III) was quite common (especially as the key of the second tonal area (STA)). Looking at table 2 we find that the keys of the FTA’s are major in all three string quartets. The exception is the slow introduction of the first string quartet. The key is a minor and therefore the metaphoric progression would be: i-III-V (the v being altered to a major dominant chord V as is the practice throughout the common practice period).

The first string quartet in a minor

The slow introduction

In the A part of the slow introduction of the first quartet there has indeed been identified a i-III-V progression. Measures 1-6 first eighth note, the tonic, mm.7-10 third eighth note, the mediant and relative major III, and mm.10 fourth eighth note-12 the dominant V. Moreover, the mediant (III) has been treated quite emphatically with a IV-V-I cadential progression, which I modelled as a tonicization of III (mm.7-10). Whereas the progression to the mediant in minor keys is quite common in the classical style (as key of the STA), the role of the mediant is different here. It is not the key of a secondary theme zone but it is part of a harmonic progression which leads to the dominant (V) as the closure of the first phrase (a half cadence [HC]). And in that progression it is firmly established: the C major chord on the first beat of m.10 is experienced as an arrival but in retrospect it is misleading as the phrase continues to m.12. So Schumann treads the mediant in a different way.

The first tonal area (FTA)

Remember that the A1 part of the FTA is a modulating period with an antecedent starting in the home key F major and a consequent ending on the dominant C major. In the consequent we find the modulation from I to V by way of the mediant (iii, a minor). And again the mediant is quite stressed with a GER65-V7-i or predominant-dominant-tonic progression. Notice that this time I did not model it as a tonicization of iii but just as an applied progression between brackets (mm.43-45) because the elaboration is less extensive than in the A part of the slow introduction of the first quartet. Nevertheless the listener will experience a relative rest point on the second half of m.45.

So indeed there is again a I-iii-V progression.

The second string quartet in F major

To find the I-iii-V progressions in the second quartet, we need to go to the Transition. As has been shown there the progression can be found on three levels. On the highest level (of the exposition) it is a I-iii-V progression in F major. On the middle level (of the components of the exposition) it is a I (replaced by vi)-iii-V-I progression in C major as the tonic of the STA. And on the lowest level it is the I-iii-V progression in E-flat major (mm.49-53). A detailed account can be found in the paragraph on the harmonic progression in the transition.

The third string quartet in A major

In the third quartet we again have to visit the Transition to find a I-iii-V progression. And to find it you have to look at the harmonic progression in the transition from the point of view of the tonic of the second tonal area (STA), E major. True to the hallmark of this quartet the keys of the I-iii-V progression are quite hidden. They never start on their tonic but slide into it by way of a subdominant-dominant (or vii0) progression. Figure 10 of the post on the third quartet shows this. Nevertheless the progression is clear. After having reached the V of E major (B major, mm.27-35), there is the interlude in C major (VIMD of E major) only to return to B major in mm.43-45, and finally E major is established as the key of the STA.

Conclusion

As has been shown the I-iii-V progression occurs quite frequently in the string quartets (and it is also the main harmonic progression in the exposition of the piano quartet as has been shown in my analysis of the first movement). So I think that one could say that the string quartets give evidence that Schumann brought the so strongly formulated metaphor in practice and thus contributed to the development of the third relationships which would be quite common in the romantic period.

Ambiguous tonality

Another aspect that is found in all the string quartets (and in the piano quartet as well) is the fact that Schumann likes to leave us in doubt as to what is the prevailing key. In each piece there are parts where this uncertainty occurs.

The first string quartet in a minor

In the first string quartet it concerns the A2 part of the first tonal area (FTA). It has a strong tendency towards the dominant C major, which is quite normal for an A2 part of a ternary form. The A2 part starts with a C major chord but all ready in the second half of m.50 the seventh of the chord occurs and points back towards F major. This is reinforced by the subdominant (g minor) with its applied dominant in m.52. Schumann plays with C major as dominant of F major (second half of m.54) and F major as subdominant of C major (first half of m.55).

The second string quartet in F major

The A2 part of the FTA

In the second quartet it is again the A2 part of the first tonal area (FTA) that causes confusion regarding the key. This A2 part is in the key of g minor (the supertonic of F major) which is indicated by the leading tone F-sharp. Nevertheless there is a strong tendency towards B-flat major (the relative major of g minor) because the cello is pressing a B-flat throughout this part of the FTA. Ambiguity between these keys (g minor and B-flat major) is also found in the second half of the exposition of the first movement of the piano quartet.

The second tonal area (STA)

As has been shown in the analysis of the STA there is an initial ambiguity about the key of this component of the exposition. The cadence in mm.78-80 resolves the matter: C major it is. In retrospect this also makes clear that the G major chords in m.72 and m.76 should be interpreted as half cadences (HC).

Looking again at mm.68-71 second beat one sees a mixture of three subdominant chords (of C major):

- as explained in the analysis when following the soprano voice from m.69 onwards there is a triadic melody in d minor (ii), with a passing note on the third beats of m.69 and m.70;

- secondly, when looking at the first beats of mm.69-71 in the same voice there is an arpeggio in F major (IV);

- and when looking at the first two beats of m.71 we find an a minor chord (vi). This is for the ear reinforced by the twice occurring leading tone to a minor, the G-sharp on the third beats of m.68 and m.69.

As was shown in fig.2 these chords (ii, IV and vi) are strongly related by way of third relations and Schumann takes us as it were through a carousel of these chords which can be seen as a result of the contrapuntal imitation like structure he chose. I am sure however that he was very well aware of the harmonies he used (as opposed to composers in the Renaissance who thought horizontally and not vertically in terms of harmonies). The overall impression is that of a subdominant.

The third string quartet in A major

Looking at the analysis of the first period of the STA of the third string quartet we find the same ambiguity of key as in the A2 part of the FTA of the first string quartet. Again it concerns the relation between two keys, one the dominant of the other, the other the subdominant of the first one. The keys are A major and E major.

As we are in the second tonal area this is literally E major, the key of the subordinate theme. So this is the local tonic. But as shown in fig.12 the repetition of the basic idea and the consequent of the antecedent of the first period have a strong inclination towards A major. In this context it is the subdominant of E major, but on the level of the exposition (and the whole of the first movement) it is the home key.

So whereas the STA starts with a basic idea firmly in E major, the rest of the sentence pulls back toward the home key. Of course one could say we are lingering on the subdominant, but as that happens to be the home key this gives this an added charge. Are we already going back to the home key? Did we just touch on the dominant? No we did not, as the sentence in the consequent returns to E major and ends with a imperfect authentic cadence (IAC) in that key (fig.12, mm.61-62).

As Schumann repeats the whole period the same game is played twice although the listener now is aware of the fact that the prevailing key is E major. So an interpretation of A major as subdominant of E major is more likely. The surprise is of course that there is no closure of the phrase and it takes an extension to reach the perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in E major

Conclusion

Overlooking the various ways in which Schumann shaped ambiguity in keys in the string quartets we can distinguish three types of doing so:

- A play between the home key, the dominant of the home key and the home key as subdominant of its dominant. This is the case in the A2 part of the FTA of the first string quartet and also in the STA of the third string quartet.

- A play between a key and its relative (be it either minor or major). It was found in the A2 part of the FTA of the second string quartet. In this case, it involves the key of g minor (the super tonic of the home key F major) and its relative major B-flat major. The same keys can be found in the ambiguity in the second half of the exposition of the piano quartet.

- The last form of ambiguity is perhaps the least obvious or even vague as found in the STA of the second string quartet. It is a rotation through a related set of (predominant) chords which only acquire meaning after the key of the local tonic has been established.

Concluding one could say that his treatment of ambiguity of keys is another way in which Schumann paved the way to romanticism in music. Among others Brahms was a master in this respect and an example can be found in my post on periods.

The contrapuntal aspect [H3]

The last aspect to consider in this comparison of the string quartets is the way in which Schumann made use of his exercises in counterpoint and fugue in the spring of 1842.[9]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 244. Surveying the analyses of the quartets, the following picture emerges:

The first string quartet

As demonstrated in the analysis of the slow introduction of this quartet, here we are dealing with a very fugato-like theme that is ultimately better referred to as imitation. There is however a contrasubject and the association with the fugue is evident.

In the same quartet the transition starts even more like a fugue. The first three entrances are almost flawless as a fugue (and are labelled that way), but after that Schumann starts improvising and eventually takes another turn.

So in this first quartet that Schumann wrote after his inquiry into counterpoint earlier that year the impuls that this studie gave him is clearly recognizable.

The second string quartet

In the second quartet there are also two spots where counterpoint is prominent. The first one is the A1’ part of the first tonal area. As has been shown there the u1 motive is repeated eight times in the A1’ part. In the consequence of the sentences (mm.37-40 and mm.45-48) the u1 motive is combined with the b motive in a contrapuntal way.

And then of course the second tonal area (STA) in which the melody of the first violin is literally repeated in the second violin in a canon-like way. This is repeated in the first violin and alto.

The second string quartet can therefore also be said to contain quite some contrapuntal elements.

The third string quartet [H4]

In the third quartet the counterpoint is clearly less prominent and a more homophonic style prevails (i.e. a melody with accompaniment). The first place where one could speak of counterpoint is the first segment of the transition. The imitative structure was explained in detail there.

And secondly an imitation can be found in the internal extension of the overall period of the second tonal area (STA). It is only a short fragment in the whole of the STA but nevertheless recognizable as an imitative texture.

Conclusion

Schumann did use the knowledge of counterpoint he acquired during his unhappy – but also fruitful – period alone in Leipzig in the spring of 1842. It has a strong presence in the first string quartet and makes that this quartet gives a somewhat stern and academic impression, especially in the first movement.

The use in the second quartet is much milder and this quartet already has a very cheerful and exuberant character of its own. In the second tonal area it is again very present however.

In the third string quartet it seems that the contrapuntal aspect has been completely integrated in Schumann’s compositional style. Counterpoint is a means as expression but no longer an end in itself.

Epilogue

This is the end of this small series on Schumann’s string quartets. It only concerns the expositions of the first movements but what a wealth of material they contain to be discovered. It is a beginning to an understanding of what Schumann did in his chamber music year. Coming from mainly compositions for piano he progressed through Lieder (1840) and symphonic compositions (1841) to the year of chamber music (1842). His compositions in this genre certainly have earned their place in the canon of classical music (however debatable this concept may be).

Notes

| ↩1 | John Daverio, Robert Schumann: Herald of a “New Poetic Age” (New York etc.: Oxford University Press, 1997), 242-244. |

|---|---|

| ↩2 | Steven G. Laitz, The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis and Listening (4th Ed (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2016), Chapter 27: Sonata form. |

| ↩3 | William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998), Chapter 13: Sonata form. |

| ↩4 | Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), Chapter 2: Sonata form as a whole. |

| ↩5 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 251. |

| ↩6 | Caplin, Classical Form, 17-21. |

| ↩7 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, 636. |

| ↩8 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, 367-368. |

| ↩9 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 244. |

Recent Comments