Schumann string quartet no 2 – an analysis

Last updated on January 19th, 2025 at 02:43 am

Table of contents

Introduction

As I was working on the analysis of Schumann’s piano quartet in E-flat major, op.47, I read the book by John Daverio on Schumann.[1]John Daverio, Robert Schumann: Herald of a “New Poetic Age” (New York etc.: Oxford University Press, 1997). A remarkable feature of the piano quartet is that the exposition has no second theme and that the articulation of the dominant is late in the exposition (find my analysis of the first movement of the piano quartet here). Daverio compares the way in which Schumann and Haydn handle the sonata form and remarks “Similarly, Haydn’s teleological sonata forms […] find a counterpart in the delayed articulation of the dominant that characterizes the exposition of the first and last movements of Schumann’s Opus 41, no 2 [string quartet]”.[2]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 251.

That made me curious so I started looking into the second string quartet. But then my curiosity went further and I wondered what Schumann did in the other string quartets. After all he wrote them in a time span of seven weeks: beginning of June to the 22nd of July 1842.

After drawing some sketches for comparing the quartets I decided to write a post about the comparison. But before you can compare them you need to analyse them. So I ended up with a project that will provide for a small series of four posts: one for the analysis of each of the string quartets (the exposition of the first movements only) and a fourth post for the comparison.

This is the second post in this mini series and deals with the second string quartet in F major, op.41 no.2.

I again want to thank Menno Dekker – my former professor at the conservatory of Amsterdam – for the very useful discussions I have had with him. It keeps improving my understanding of music and more particular music analysis. Our relation has grown into a genuine friendship with the music theory and analysis as a perpetual source of inspiration.

Historical context

In the beginning of 1842 Schumann had quite a difficult time, as a matter of fact it was “the first major crisis of Schumann’s married life”.[3]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 242. Clara was on a concert tour in northern Germany and Robert accompanied her. After one of the concerts (in Oldenburg on the 25th of February) Schumann was not invited for the after concert party. Clara decided to attend on her own and Robert was furious and returned to Leipzig alone.[4]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 243. In the weeks to follow – spent alone in Leipzig – “Schumann occupied himself with exercises in counterpoint and fugue”.[5]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 244. As will be shown hereafter the fruits of this investigation in counterpoint and fugue are readily traceable in the string quartets opus 41.

The strings quartets are dedicated to Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, a good friend of Robert Schumann.

Practical information

In this text a lot of references are made to the score of the string quartet. This is done by means of the measure number (always within the first movement). Ideally you have a score with measure numbers at your disposal. A score can easily be downloaded from IMSLP.

In general notes on analysis you can find some remarks on abbreviations, notation and concepts. Some books that I have been consulting can be found in consulted literature. At least all references made to literature in the notes should relate to entries in the consulted literature. The music examples are made in Musescore 4.

As for a notational convention of major and minor keys: I will use capitals for major keys and lower-case letters for minor keys. For major keys I will often add the word major and for minor keys the word minor, but in music examples and diagrams the words major and minor will in general be omitted. So B major or B for B major and b minor or just b for b minor.

Finally it must be mentioned that although automatic adjustments are made to view these posts on tablets as well as mobile phones, they can best be accessed on a computer/laptop. The reason being that there are various tables and lists (like abbreviations) of which the columns will appear one beneath the other (especially on a mobile phone). If that is the case the coherence will be lost.

Schumann: the string quartet in F major, op. 41 no. 2

This string quartet is the second composition Schumann wrote after his thorough investigation in counterpoint and fugue. The influence of his studies is clearly recognisable in this quartet also. Whereas both the string quartets op.41 no.1 and 3 start with a slow introduction (very different in character however) this string quartet has none. The joyous Allegro vivace starts immediately in a three-four meter, which from time to time resembles a six-eight meter (over two bars). Again the key of this Allegro vivace is F major (as the Allegro of the first quartet), but this time it is also the key of the whole quartet as opposed to the first quartet which is in a minor.

The exposition

The Allegro is in sonata form and the exposition contains the following elements:

Measure

1-48

49-68

69-80

81-96

Key (relative to F major)

I

I – V/V

V (C major)

V – I

Table 1: layout of the exposition

The main theme or First Tonal Area (FTA)

A downloadable PDF of the FTA in piano score format with my annotations can be found here. The FTA can again be analysed as having three parts and is definitely a ternary form:

Measure

1-16

17-32

33-48

Section

A1

A2

A1′

Key (relative to F major)

I

ii (g minor)

I

Table 2: layout of the Main Theme or First Tonal Area

The A1 part

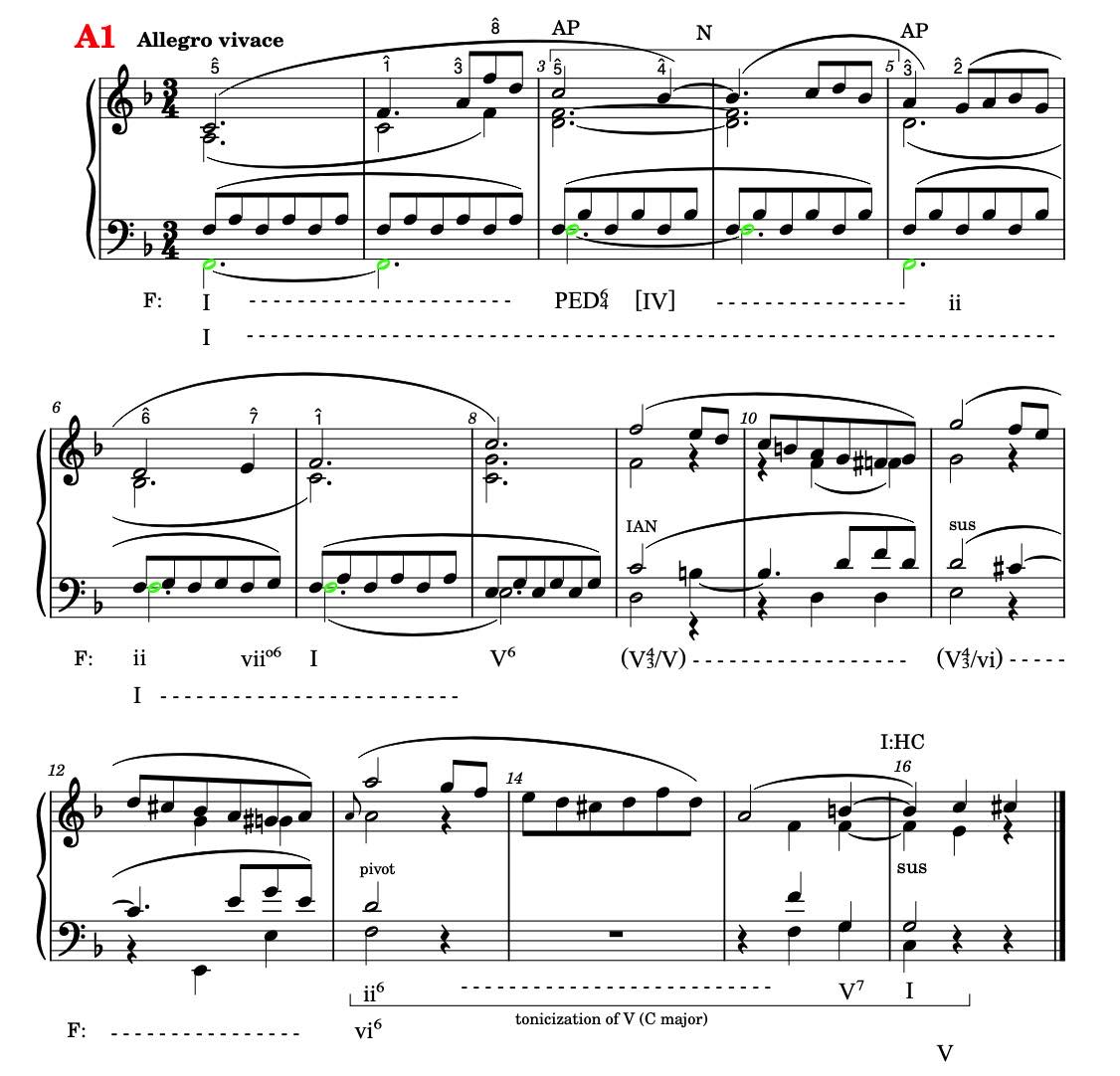

Figure 1 shows the A1 part. When listening to it one is struck by the jubilant character. After the first phrase which has a weak closure in m.8, there follow even more shouts of joy in the melodic line of the first violin. The whole phrase ends with a half cadence in the tonic (I:HC) in mm.15-16. The A1 part feels like a unity with two high points in m.3 and m.13.

fig.1 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.2, i, mm.1-16

When trying to say something about the form, the first thing to notice is that there are no real repetitions of motivic material in these sixteen measures. Of course the motive of mm.9-10 is repeated in mm.11-12 and slightly varied in mm.13-14, but these repetitions cannot be interpreted as repetitions in the sense of a sentence or period. [See my posts on sentence and period for an explanation of how these concepts deal with repetitions.]

Then perhaps first consider the harmonic structure of A1. The movement starts in the tonic F major and the third and fifth scale degree of the tonic chord are raised to the fourth respectively sixth scale degree in mm.3-4. The bass however remains on F natural. So the chord is a IV64 chord but Laitz calls this a pedal sixth-four chord (PED64) because it can be seen as a neighbour note figure in two voices (here in the second violin and the viola).[6]Steven G. Laitz, The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis and Listening (4th Ed (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2016), 304-305. In fact it functions as a prolongation of the tonic.

After this follows a ii – vii06 – I progression (mm.5-7) still over the pedal of F natural. So the effect of the harmonies is weakened and a strong feeling of the prolonged tonic is tangible.

Only in m.8 the pedal is left and a dominant V6 sounds, a weak half cadence as the dominant is not in root position. When the listener hears mm.9-10 the chord of m.8 appears in retrospect to be a passing or connecting chord to the buildup in mm.9-13.

Now these measures melodically strongly suggest a sequential progression but harmonically they are not. Measures 9-10 are in G major and mm. 11-12 in A major. In m.13 we find a d minor chord.

So my interpretation would be that the G major chord is the announcement of C major in the form of its (applied) dominant and that then a cadential progression in C major follows: ii6 – V7 – I. The ii is preceded by its applied dominant (A major). Therefore I made mm.13-16 a tonicization of C major, a cadential area leading to the half cadence in F major (I:HC).

Now when trying to identify the (a) form of this A1 part I would say that mm.1-8 mostly look like an antecedent ending with a weak cadential progression in mm.7-8 and that mm.9-16 have the characteristics (at least harmonically) of a continuation. There is new motivic material so I don’t think it is just an expanded cadential progression.

The form would then mostly resemble what Caplin calls a hybrid theme of type 1: antecedent + continuation.[7]William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998), 59.

The motives of the A1 part of the main theme

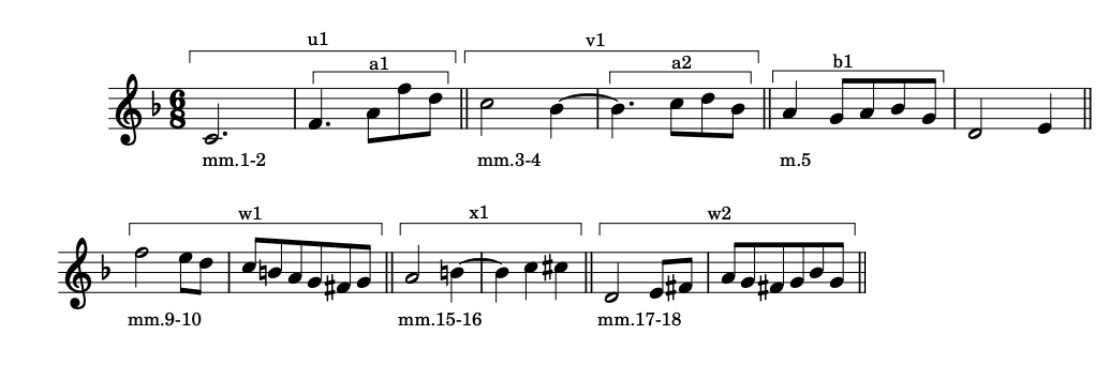

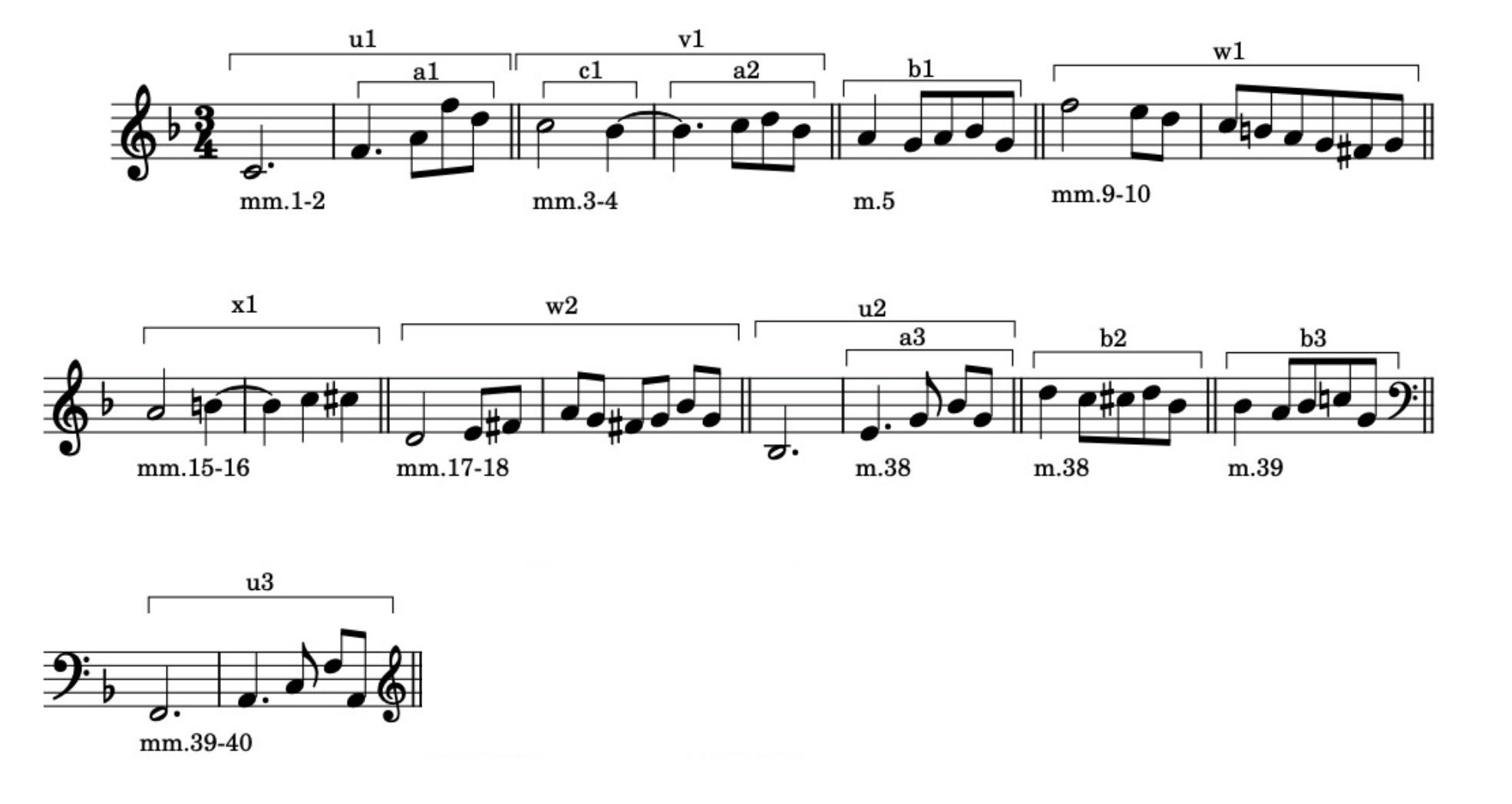

Looking at the motives used, fig.2 shows the ones encountered in the A1 part of the main theme.

fig.2 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.2, i, motives of the A1 part of the main theme

The A2 part

Figure 3 shows the second part (A2) of the ternary form which starts in g minor, the super tonic of F major. The first part A1 ended on a half cadence in F (I:HC) and Schumann made the transition by way of a chromatic passing note on the third beat of m.16 (the C-sharp; see fig.1). This leads to the D octave in the violins which is the dominant of g minor. This is analogous to the opening of the movement which starts in the key of F major with a C natural in the soprano melody.

fig.3 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.2, i, mm.17-33

The form of the A2 part is clearly a sentence. See my post on the concept of sentence for an explanation. This sentence respects the 1:1:2 proportion with an absolute length of 4+4+8 bars. The repetition of the basic idea in mm.21-24 is almost exact, the only difference being that the first violin plays a G natural in m.21 ending on a A natural in m.22. The G natural emphasises the key of this part which is nevertheless again very ambiguous. The start in m.17 is not in root position but in first inversion and as a matter of fact the root position of g minor does not occur, except perhaps in m.22. But there it is not very convincing as the bass makes a B-flat octave jump. The prominent B-flat in the bass pulls towards B-flat major, the relative major of g minor. So again there is this ambiguity of key which is also found in the A2 part of the ternary main theme of the first string quartet and in the second part of the exposition of the first movement of the piano quartet.

The motive used in mm.17-18 (second violin) rhythmically closely resembles the motive w1 of the A1 part and will be called w2. The melodic contour starts in the opposite direction and is more stationary around the local tonic g minor. The mm.19-20 use the motive x1 of the A1 part.

The continuation uses part of the basic idea (another variant of the the w1 motive) without the x1 motive and can thus be called a fragmentation of the basic idea, which fits perfectly in the concept of continuation.

In m.29 the cadential area starts, still with the same fragment of the basic idea. The harmony can both be seen as a first inversion of g minor (the key of the A2 part) and as a predominant of F major to which we are about to return. So m.29-30 are the pivot back to F major. What follows are two measures in the dominant of F major: the half cadence (HC) with which the A2 part ends.

The motives of the main theme as far as the A2 part

Looking at the motives used, fig.4 shows the ones encountered in the first tonal area in the A1 and A2 parts.

fig.4 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.2, i, motives of main theme as far as the A2 part

The A1’ part

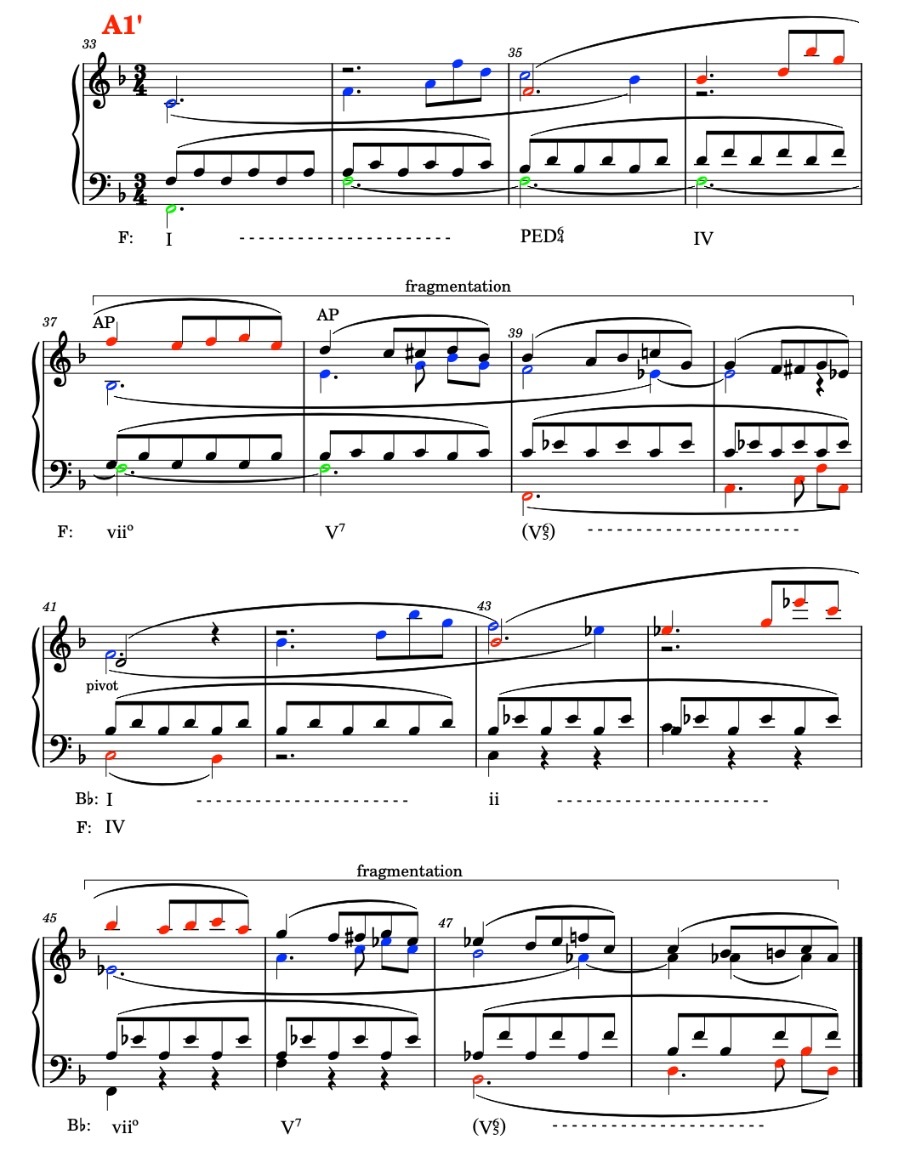

The A1’ part of this ternary form is again 16 bars long, exactly the same length as the A1 part. Schumann varied the form however. There are two 8 measure phrases (mm.33-40 and mm.41-48 respectively), the first one of which starts in F major and ends in a F dominant seventh chord. The second one starts (not surprisingly) in B-flat major and ends with a B-flat dominant seventh chord. As we will shortly see this is a nice forebode of the E-flat major in m.49, the start of the Transition. Figure 5 shows the piano version of the A1’ part.

fig.5 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.2, i, mm.33-48

So what happens here? Let’s focus first on the first eight measures. The alto voice (second violin) starts with the u1 motive of the opening theme (fig.1). It is shown in blue in fig.5. After two measures the first violin starts an imitation (m.35, shown in red). Notice that the B-flat in the first half of m.36 fits both in the first entrance by the second violin and in the second entry by the first violin. Looking at fig.1 this corresponds with the second and fourth measure of the opening. One could also say this is in accordance with the second measure of the u1 and the second measure of the v1 motive (both variants of the a motive). So Schumann designed a theme for the first tonal area (FTA) very well suited for contrapuntal (imitative) treatment. In fact there are eight entrances in the A1’ part, four of which are in the first phrase. The last entrance in the first phrase in the cello (m.39) ends in the second phrase. It is yet another example where form and process are not synchronous.[8]See chapter IV, Hierarchic Structures in Leonard B. Meyer, Explaining Music: Essays and Explorations (Berkeley [etc.]: University of California Press, 1973). The same happens at the end of the A1’ part: the cello entrance ends in the Transition.

The motives of the main theme

Schumann made changes to the motives as to fit them in the harmonic context. Figure 6 shows the motives of the first tonal area (FTA) or main theme including the A1’ part.

fig.6 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.2, i, motives of the main theme

Notice the tritone interval in the u2 variant. It is the tritone in the C dominant seventh chord of which the root enters in m.38 in the viola. Schumann does not proceed to the tonic F major chord but to a F dominant seventh chord and prepares for the next phrase which is in B-flat major. It is a copy of the first phrase, raised one fourth.

Looking for the last time at the first phrase of the A1′ part we see a repetition of the b motive in mm.37-40 which can be seen as a fragmentation of the main theme. This points towards a continuation and therefore the phrase can be interpreted as a sentence. So the whole of the A1’ part can be seen as a sequence with a nested sentence structure. In the continuation part of the sentences the b motive is combined with the u1 motive in a contrapuntal way.

This completes the analysis of the first tonal area (FTA).

.

The Transition (TR)

The Transition is 20 measures long and is shown in fig.7. I think it is possible to structure this as follows:

Measure

49-56

57-64

65-68

Section

2+2+4 sentence like structure

2×4 sequence

cadential area

Table 3: layout of the Transition

As we already saw this is not a progression from the home key (F major to the key of the second tonal area or subordinary theme [C major]). The third part of the main theme (A’, mm.33-48) ended on a B-flat dominant seventh chord in first inversion (fig.5) and accordingly the Transition starts in E-flat major.

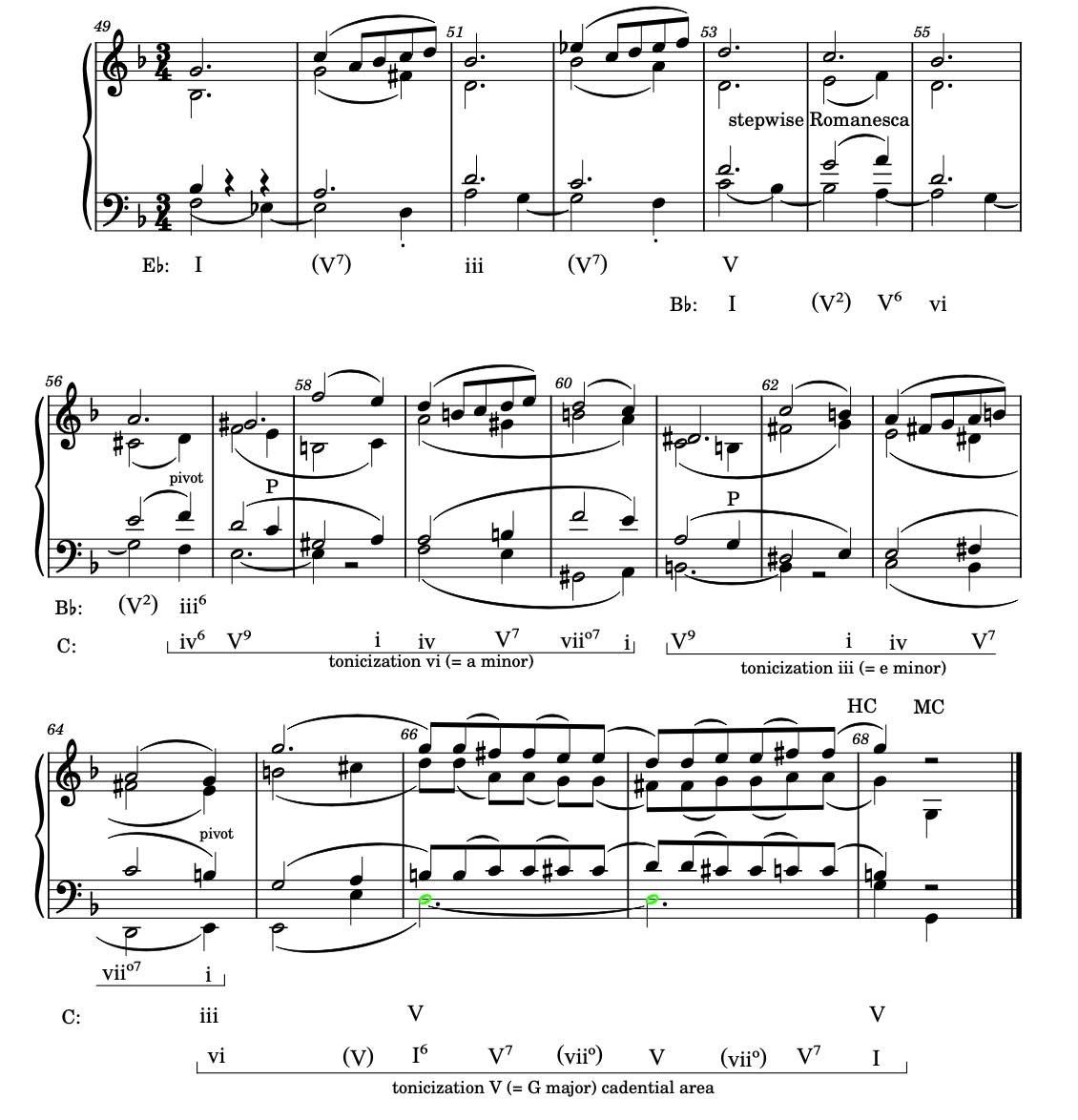

fig.7 Schumann string quartet op.41 no2, i, mm.49-68

As the A’ part of the first tonal area already moved away from the tonic it can in fact be seen as an overlap between the main theme and the transition. Again I will first look at the form and motives and then dive into the harmonic progression Schumann used.

The Transition: form and motives

As can clearly be seen in fig.7 mm.49-50 and mm.51-52 are identical apart from the upwards transposition by a minor third (from E-flat to g minor). I interpreted this as the basic idea and sequential response of a sentence-like construction. If interpreted this way we expect a continuation of the sentence which should be a four measure phrase. This can indeed be found in mm.53-57. As I already gave away in fig.7 the formula we find here is a variant on a stepwise Romanesca. I’ll come to that in a minute.

For now let’s continue with the main structure of this Transition and look at the next eight bars (mm.57-64). They are clearly two identical phrase of four bars each, be it a fourth apart (a minor respectively e minor).

The jump of a seventh in mm.57-58 and mm.61-62 in the soprano is new although it reminds us of the main theme: the C natural in m.1 and the B-flat in m.4 (fig.1). This is a much more compact form. The mm.58-60 are a variant on the v1 motive in which the second half does not come from the a-family of motives but from the b-family. Figure 8 shows these motives.

fig.8 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.2, i, motives up to the Transition

The last four measures (mm.65-68) form the cadential area towards C major, the key of the second tonal area (STA) or subordinate theme. It is a contrary stepwise motion from G major to its dominant (m.67) and back on a D pedal.

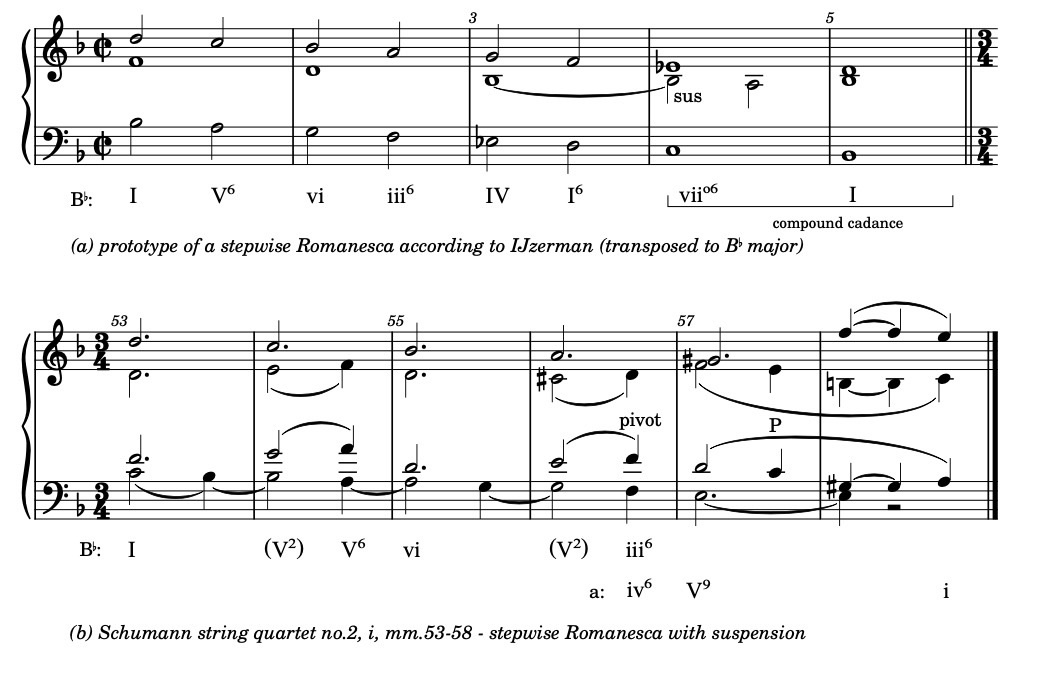

The stepwise Romanesca

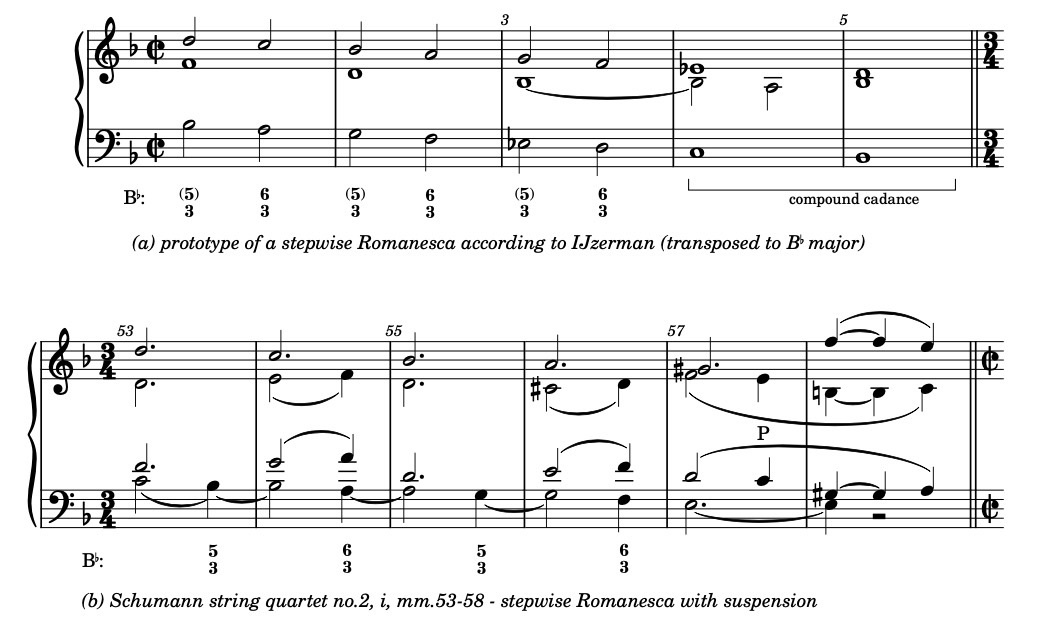

Let’s now turn to mm.53-57. As already mentioned Schumann is playing again with one of the Galant schemata, this time a stepwise Romanesca. In the post on Schumann’s first string quartet I quoted some explanation of the Galant Style from a book by Job IJzerman.[9]Job IJzerman, Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Figure 9 shows the prototype of a stepwise Romanesca according to IJzerman[10]IJzerman, Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento, 42. (a) and the version of Schumann’s second string quartet (b).

fig.9 stepwise Romanesca: figured bass

The characteristic features are the stepwise descending bass line and a voice that accompanies the bass in parallel thirds. In both (a) and (b) this is the soprano. The stepwise character is accomplished by taking the first inversion of every second chord as can be clearly seen in the figured bass. Schumann added suspensions in his version.

So in m.53 he starts with an incomplete accented neighbour note (IAN) in the bass: the C natural which resolves to B-flat on the third beat, a B-flat major chord in root position. The B-flat becomes a suspension in m.54 which resolves on the third beat of that measure to a F major chord in first inversion, the dominant of B-flat. On the suspension Schumann adds a passing note (the E natural in the second violin in m.54) which makes the suspension chord an applied dominant of the F major to come. This is repeated in mm.55-56, be it that the C-sharp in the second violin in m.56 is a neighbour note and not a passing note. Figure 10 shows the same but now with roman numerals.

Clearly can be seen that Schumann steps out the Romanesca after the second inverted chord (four steps in the Romanesca). It is in m.57. In stead of going to a IV (an E-flat major chord) he makes a chromatic alteration with an E natural in the bass and a G-sharp in the soprano, which makes the d minor chord on the third beat of m.56 a pivot chord. We enter the world of a minor and the chromatically altered chord in m.57 is a V9 of the a minor to come. Wow, I love Schumann!

fig.10 stepwise Romanesca: roman numerals

A few more remarks on the stepwise Romanesca. Of course the question is: did Schumann think about this type of formula as a Romanesca? I don’t know. I haven’t found any reference to Galant style schemata in the literature about Schumann but then I don’t know all the literature about Schumann or the exact way composers operated in his age.

Another way to look at the Romanesca is to see it as a sequence. That would be a D3(-4/+2) sequence, meaning that it steps down a fourth and than steps up a second (resulting in a descending third sequence: D3).

If every second chord is not inverted then the resulting form is a Romanesca (without the addition stepwise). A very famous example of this is the Pachelbel canon in D major. Look here for a video explaining the Pachelbel canon and its influence on pop music. For a video on a more historical inquiry into the Romanesca look into earlymusicsources.com.

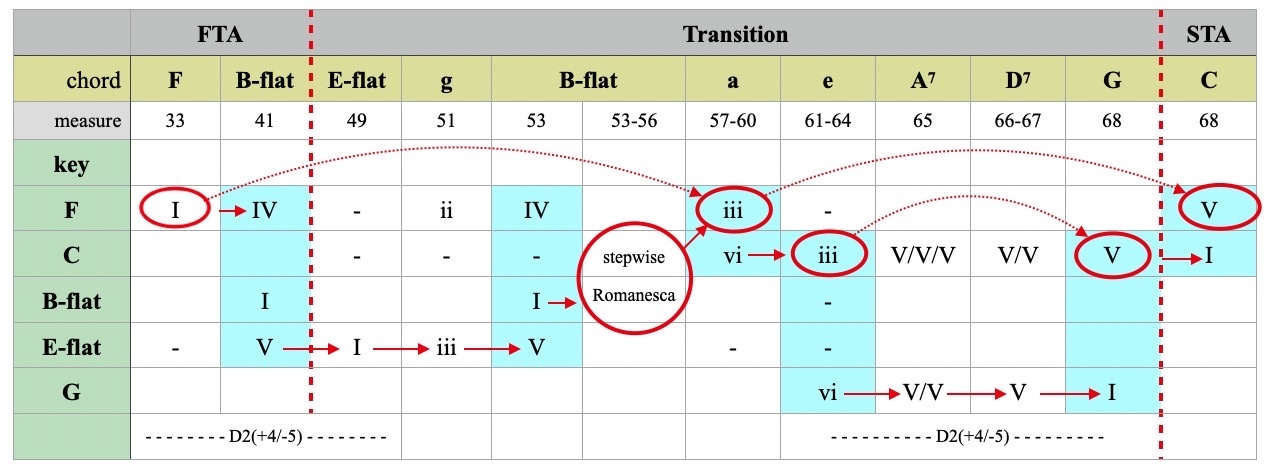

The Transition: harmonic progression

So how did Schumann this time make the harmonic transition from F major to C major. Figure 11 shows a diagram of this transition.

The diagram again tries to explain how you can look at different levels of analysis at the chord progression in a certain section of a piece. In this case these levels are:

- the level of the exposition (and in fact of the Allegro as a whole)

- the level of the various components within the exposition (FTA, Transition, STA, Closing Section)

- the level of segments within these components (for instance a cadential area).

fig.11 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.2, i, levels of analysis in the transition

The keys as mentioned in the first column of the diagram correspond to these levels as follows:

- F major, as the key of the Allegro, and the key of the component first tonal area (FTA)

- C major as the key of the component second tonal area (STA)

- B-flat and E-flat as segments within the Transition; G major as the key of the cadential area within the Transition

Again the choice of the key for the second tonal area (STA) is very classical. It is C major, the dominant of F major (analogous to the first string quartet). The chords as encountered in the transition are shown in the second row and the third row gives the measure(s) in which they are found. The cyan coloured cells in a column mean that a chord can belong to more than one key; they can be used as a pivot chord to go from one key to another. The partial cyan columns are a sort of elevator to go from one key to another. The red arrows, together with the elevators, lead you through the harmonic progression.

And now for some explanation of fig.11. The second and third column concern the A’ part of the main theme (therefore labelled FTA, fig.5). Already mentioned is that Schumann starts modulating here and this part is in fact an overlap with the Transition. And how does he modulate? In fact it is a plain falling fifth sequence in two steps: F – B-flat – E-flat. Then he decides he is far enough off (because the aim of the transition is C major) so having arrived on E-flat (with three flats, pretty far away from C major with zero flats) he starts moving the other way: up (clockwise) in the circle of fifths.

The Transition starts in m.49 in E-flat major. As was shown in the post on Schumann’s piano quartet he had in mind a division of time (past-present-future) which he mapped on the tonic triad. The quotes of Schumann that explain this idea can be found here. As we examine the progression from m.49 to m.53 we find exactly this tonic – mediant – dominant progression (shown in the row labelled E-flat). Coincidence? I would say: no.

In m.53 B-flat major is reached be it with a suspension as was explained in the paragraph on the stepwise Romanesca. The stepwise Romanesca, which is in B-flat major, takes us to a minor. Here are two questions to be answered:

- why a minor?

- what is the relation between B-flat major and a minor, or: how is the transition made between B-flat major and a minor?

Let’s start with the first question: why a minor?

Looking at the global picture we are on our way from F major to C major. What is a minor in F major? Yes, the mediant! And what is a minor in C major? The submediant and as such the first replacement of C major. With Schumann’s metaphorical tonic triad in mind the choice for a minor is quite conceivable. In the F major context it is part of the tonic – mediant – dominant progression. On the other hand it is the first replacement of C major and looking ahead at the progression to e minor and G major (the mediant and dominant of C major) there is again the tonic – mediant – dominant progression, be it that the tonic is represented by its first replacement (the submediant), and this fits with the double role of a minor as mediant of F major and submediant of C major.

The second question: what is the relation between B-flat major and a minor, or: how is the transition made between B-flat major and a minor?

Well, how the transition is made is explained in the paragraph on the stepwise Romanesca. It is a chromatic alteration in a stepwise Romanesca. But B-flat major can also be seen as the Neapolitan chord of a minor. So apart from the technical transition by way of a chromatic alteration there is also a functional relationship between B-flat major and a minor: the first mentioned is the Neapolitan of the second. That is why the ear perceives this as quite smooth.

After the a minor tonicization in mm.57-60 there follows a tonicization in e minor. The reason for this has already been explained: it is the mediant in the move to the dominant of C major: G major, another tonic (replaced by vi) – mediant – dominant progression.

With e minor a chain of applied dominants starts, also perceivable as a descending fifth sequence. It is the cadential area of the Transition leading to the key of the second tonal area (STA), C major.

To summarize: the tonic – mediant – dominant progression occurs on three levels:

- from E-flat to B-flat; mm.49-53

- from a minor (replacement of C major) to G major; mm.57-68

- from F major to C major; mm.33-68

This ends the analysis of the Transition.

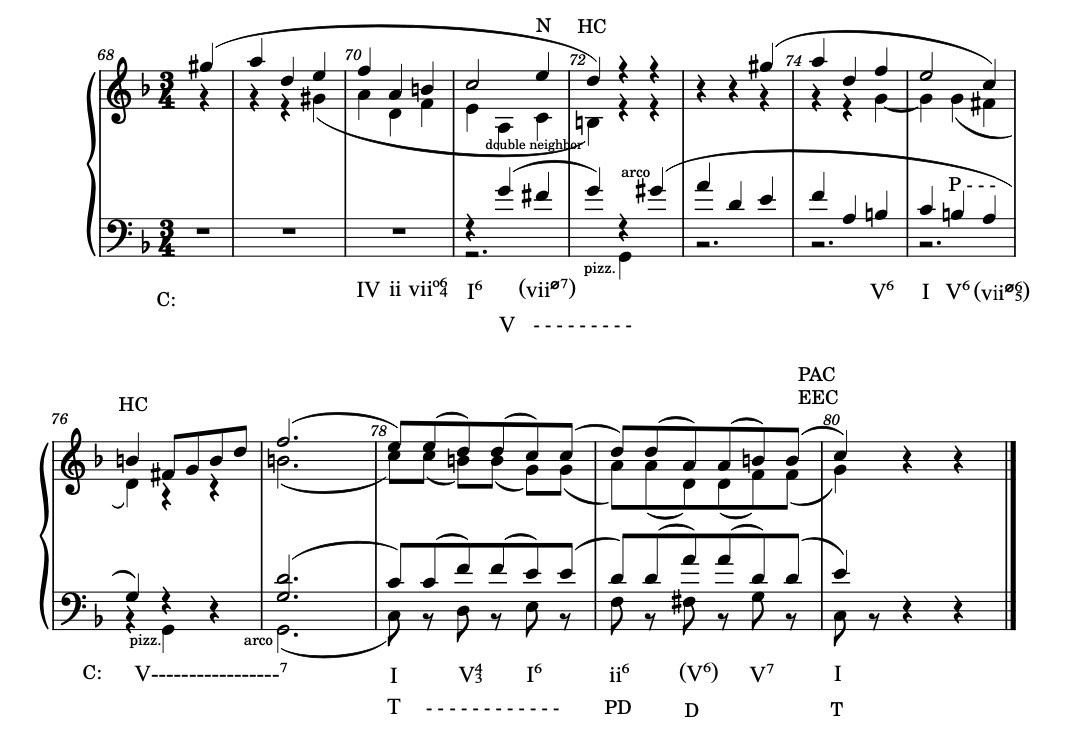

The Second Tonal Area (STA) or subordinary theme

The STA is a compact 12 measures long and brings us completely back to the contrapuntal style. Figure 12 shows the piano score. The theme is a simple two voice imitative melody starting in the first violin and than imitated in the second violin.

fig.12 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.2, i, mm.68-80

The key is not immediately clear but the mm.69-70 can be seen as an arpeggioed subdominant chord (ii) in second inversion (a d minor chord). The B natural on the third beat of m.70 is the leading tone to C major which follows in m.71. The first phrase closes with a half cadence (HC). To understand why the whole phrase should be considered in the key of C major we have to look at mm.79-80. It is a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in C major.

The four measure phrase is repeated in the viola and first violin (mm.73 with upbeat to the second beat of m.76). This also ends with a HC.

If the STA is read as a sentence-like construction than the last four bars are the (shortened) continuation. They form a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in C major. This cadence is at the same time the essential expositional closure (EEC) in terms of Hepokoski and Darcy. It is often the first perfect authentic cadence in the new key (the key of the second tonal area) as is the case here. The motive used is very similar to the motive in the cadential area of the Transition (mm.66-68, fig.7).

The form is rather free so the STA could also be interpreted as a parallel period where the antecedent and consequent both end with a half cadence (HC). In that case the last four measures are an internal extension with the real closure of the phrase.

The theme is quite evident so there is no explicite figure for that. Notice that the theme of the second violin starting in m.70 with upbeat is adjusted to facilitate the harmonic progression. The A and C natural in m.71 form a double neighbour of the B natural in m.72, the third of the dominant chord. A variation of this holds for the first violin starting in m.74 with upbeat.

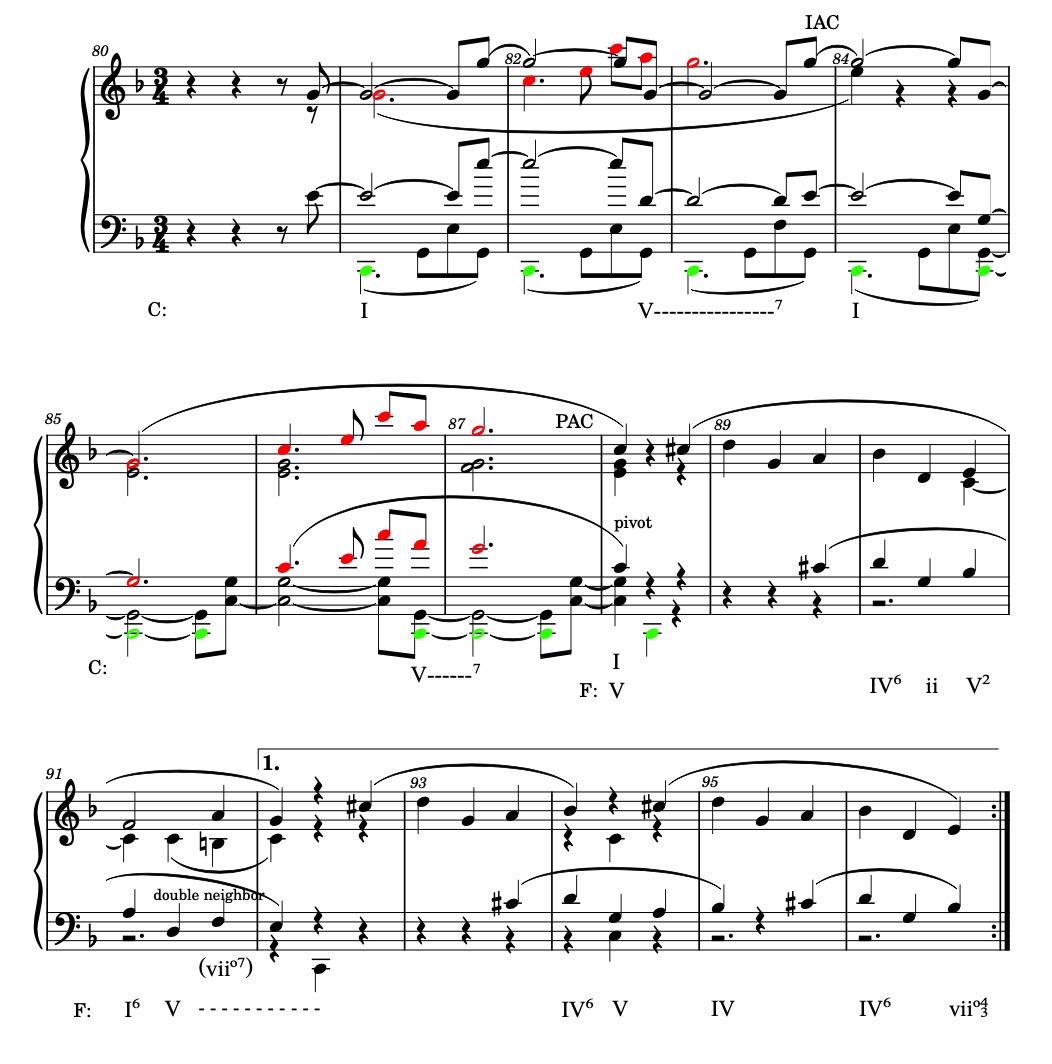

The Closing Section

In this string quartet no. 2 the Closing Section consists of 16 bars (mm.81-96). On the highest level it can be divided in two phrases of eight bars. The first phrase (mm.81-88 second beat) is characterized by the reappearance of the opening theme (FTA) and the fact that the phrase is a reinforcement of the key of C major.

The second phrase (mm.89-96) is the preparation for either the return to the beginning of the movement or the development; it uses the theme of the second tonal area (STA) and is in F major. Figure 13 shows the piano score of the Closing Section.

fig.13 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.2, i, mm.80-96

Looking into the phrases in more detail then the first phrase can be divided in two times four bars. As mentioned in the analysis of the first string quartet, according to Caplin the Closing Section consists of a group of codettas.[11]Caplin, Classical Form, 16 and 122. And indeed the first phrase consists of two codettas in C major, the first one of which ends with an imperfect authentic cadence (IAC, mm.83-84) and the second one with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC, mm.87-88). Again Schumann is very classical in his treatment of the elements of the sonata form. Notice the strong pedal on C natural in the bass (cello) which weakens the PAC. Nevertheless this is quite comprehensible as the function of the Closing Section is to reinforce the key of the second tonal area (STA).[12]Laitz, The Complete Musician, 636. So we hear the C natural all the time pervading the two codettas. No doubt about the key we are in.

The motives are of course recognizable from the opening theme (fig.4), first played by the second violin (m.81) and then by the first violin and viola (m.85), shown in red.

Measure 88 is the harmonic pivot. The first phrase has been emphasizing the key of C major as closure of the second tonal area (STA), but here C major returns to its place in the larger picture and becomes again the dominant of the home key: F major.

The second phrase of eight bars is thus in F major as can be inferred from the position of the second theme. In m.69 (fig.12) with upbeat it starts on an A natural being the sixth scale degree of C major. In m.89 with upbeat it starts on a D natural being the sixth scale degree of F major.

The second phrase starts with the four bar motive of the subordinate theme (mm.89 with upbeat – 92 second beat) but then two phrases of 2 bars follow which are almost identical. Only the last bar (m.96) is different to facilitate the harmonic progression to the vii0 of F major, an e diminished chord which functions as a kind of dominant without the bass note for the return to the opening in F major.

Notes

| ↩1 | John Daverio, Robert Schumann: Herald of a “New Poetic Age” (New York etc.: Oxford University Press, 1997). |

|---|---|

| ↩2 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 251. |

| ↩3 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 242. |

| ↩4 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 243. |

| ↩5 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 244. |

| ↩6 | Steven G. Laitz, The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis and Listening (4th Ed (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2016), 304-305. |

| ↩7 | William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998), 59. |

| ↩8 | See chapter IV, Hierarchic Structures in Leonard B. Meyer, Explaining Music: Essays and Explorations (Berkeley [etc.]: University of California Press, 1973). |

| ↩9 | Job IJzerman, Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 2018). |

| ↩10 | IJzerman, Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento, 42. |

| ↩11 | Caplin, Classical Form, 16 and 122. |

| ↩12 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, 636. |

Merci pour votre travail qui m’a bien aidé dans ma démarche d’analyse.

À propos des mesures 72 à 80 et 260 à 268, vous ne mentionnez pas qu’il s’agit de la citation du choral

WER NUR DEN LIEBEN GOTT LÄSST WALTEN (1657) de Georg Neumark (1621 – 1681).

Avec mes bonnes salutations.

Étienne Jaques Avenue de la Vogéaz 1 CH 1110 Morges Suisse

Bonjour monsieur Jaques, merci beaucoup pour votre réponse. Je suis ravi que mon analyse vous ait aidé. Merci également pour votre suggestion concernant la citation du choral de Georg Neumark. Je vais me pencher sur la question et l’inclure dans mon message. Bien à vous!