Schumann string quartet no 1 – an analysis

Last updated on January 28th, 2025 at 12:10 am

Table of contents

Introduction

As I was working on the analysis of Schumann’s piano quartet in E-flat major, op.47, I read the book by John Daverio on Schumann.[1]John Daverio, Robert Schumann: Herald of a “New Poetic Age” (New York etc.: Oxford University Press, 1997). A remarkable feature of the piano quartet is that the exposition has no second theme and that the articulation of the dominant is late in the exposition (find my analysis of the first movement of the piano quartet here). Daverio compares the way in which Schumann and Haydn handle the sonata form and remarks “Similarly, Haydn’s teleological sonata forms […] find a counterpart in the delayed articulation of the dominant that characterizes the exposition of the first and last movements of Schumann’s Opus 41, no 2 [string quartet]”.[2]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 251.

That made me curious so I started looking into the second string quartet. But then my curiosity went further and I wondered what Schumann did in the other string quartets. After all he wrote them in a time span of seven weeks: beginning of June to the 22nd of July 1842.

After drawing some sketches for comparing the quartets I decided to write a post about the comparison. But before you can compare them you need to analyse them. So I ended up with a project that will provide for a small series of four posts: one for the analysis of each of the string quartets (the expositions of the first movements only) and a fourth post for the comparison.

This is the first post in this mini series and deals with the first string quartet in a minor, op.41, no.1.

I again want to thank Menno Dekker – my former professor at the conservatory of Amsterdam – for the very useful discussions I have had with him and the suggestions he made.

Historical context

In the beginning of 1842 Schumann had quite a difficult time, as a matter of fact it was “the first major crisis of Schumann’s married life”.[3]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 242. Clara was on a concert tour in northern Germany and Robert accompanied her. After one of the concerts (in Oldenburg on the 25th of February) Schumann was not invited for the after concert party. Clara decided to attend on her own and Robert was furious and returned to Leipzig alone.[4]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 243. In the weeks to follow – spent alone in Leipzig – “Schumann occupied himself with exercises in counterpoint and fugue”.[5]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 244. As will be shown hereafter the fruits of this investigation in counterpoint and fugue are readily traceable in the string quartets opus 41.

The strings quartets are dedicated to Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, a good friend of Robert Schumann.

Practical information

In this text a lot of references are made to the score of the string quartet. This is done by means of an identification of the measure number (always within the first movement). Ideally you have a score with measure numbers at your disposal. A score can easily be downloaded from IMSLP.

In general notes on analysis you can find some remarks on abbreviations, notation and concepts. Some books that I have been consulting can be found in consulted literature. At least all references made to literature in the notes should relate to entries in the consulted literature. The music examples are made in Musescore 4.

As for a notational convention of major and minor keys: I will use capitals for major keys and lower-case letters for minor keys. For major keys I will often add the word major and for minor keys the word minor, but in music examples and diagrams the words major and minor will in general be omitted. So B major or B for B major and b minor or just b for b minor.

Finally it must be mentioned that although automatic adjustments are made to view these posts on tablets as well as mobile phones, they can best be accessed on a computer/laptop. The reason being that there are various tables and lists (like abbreviations) of which the columns will appear one beneath the other (especially on a mobile phone). If that is the case the coherence will be lost.

Schumann: the string quartet in a minor, op. 41 no. 1

This string quartet is the first composition Schumann wrote after his thorough investigation in counterpoint and fugue conducted while he was alone in Leipzig in 1842. The influence of his studies is clearly recognisable in this quartet. Before entering any detailed discussion one remarkable feature can be observed up-front: the key of the string quartet is a minor and this is the key of the Introduzione of the first movement, but the ensuing Allegro is in the key of F major, the submediant (VI) of a minor. I will come back to that later.

Slow introduction

Schumann wrote the beginning of this Introduzione of the first movement in a contrapuntal style. A downloadable PDF of the score of the Introduzione can be found here.

For the analysis of this slow introduction I would like to propose a ABA’B’ form. A would be an unambiguous 12 measures (mm.1-12) and B’ 4 measures (mm.30-33). The length of B and A’ depends on whether you take a form or a process line of approach. It would be either 11 and 6 or 12 and 5 measures.

I think some clarification would be in order and it will be given in the discussion of the B part.

The A part.

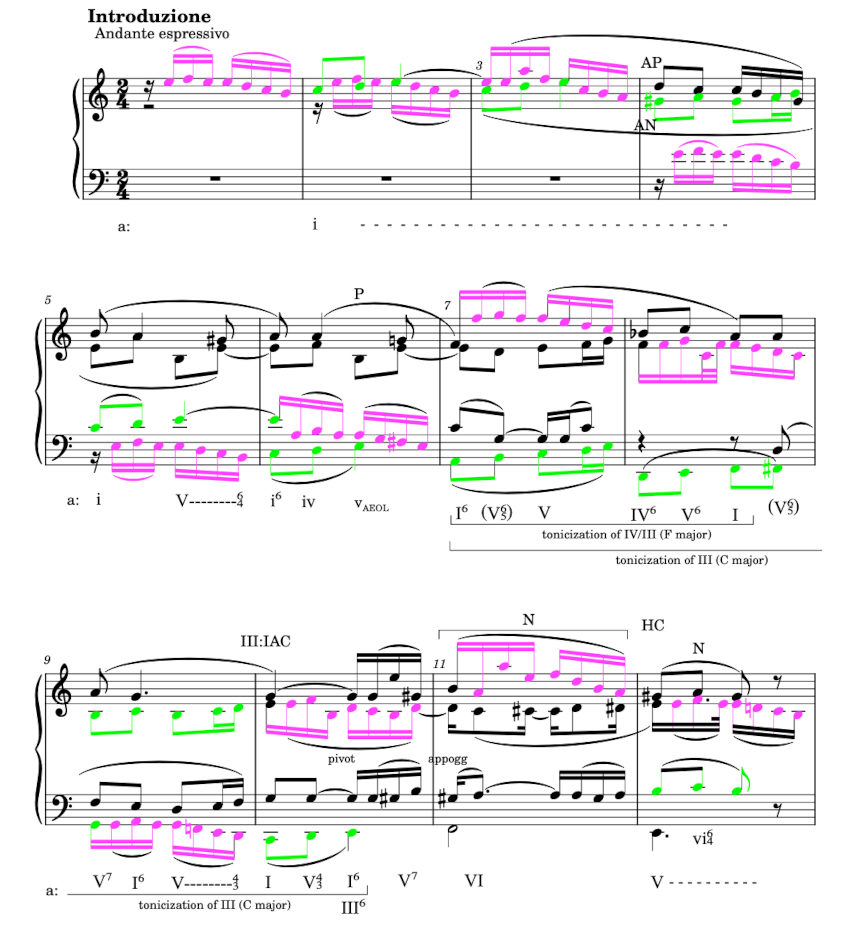

The A part is shown in fig1.1. A very fugue like subject or motive is presented in m.1 (first violin, shown in magenta). It is fugue like because it starts on the fifth scale degree (E natural) and ends on C natural, the third of the a minor scale. In m.2 immediately the second entry of the subject follows in the second violin. This entry cannot be seen as a comes as it is identical to the first entry. A comes should start a fifth higher (or a fourth lower) upon the dominant. So the second entry is a literal imitation of the first one. A contra subject is played by the first violin (shown in green).

fig.1.1 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, mm. 1-12

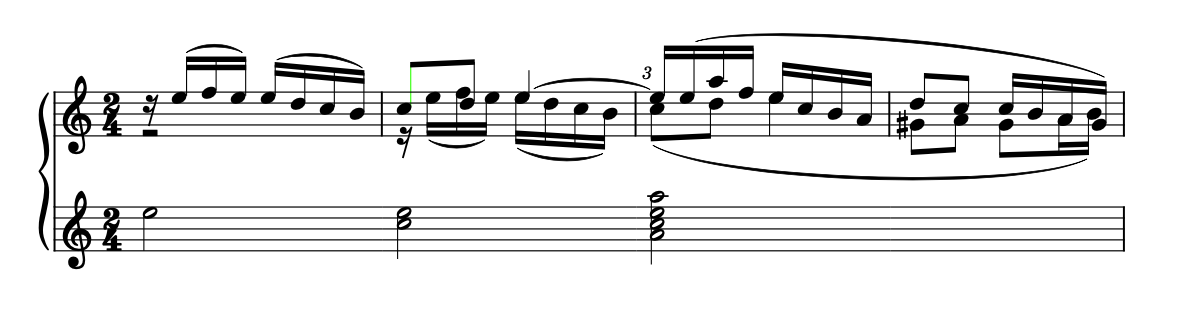

Measure 3 is deviant: the second violin plays the contra subject, but the subject – played by the first violin – is a variation of the motive. As a matter of fact this is an arpeggiation of the a minor triad. Up to the first half of m.4 is a build-up to the full a minor triad (a minor being the key of the quartet and of this introduction). Figure 1.2 shows this.

fig.1.2 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, mm. 1-4, harmonic reduction

The first eighth note of m.4 should be read as a combination of an accented incomplete neighbour (first violin) and an accented neighbour (second violin) note leading to the C respectively A on the second eighth note. Parallel on the second eighth note of m.4 a third entry of the subject appears in the viola. The contra subject is slightly varied, but in m.5 – the cello entrance – the contra subject is restored to its original form. In the second half of m.5 the harmony changes to the dominant which leads to the i6 on the first eighth note of m.6.

And from here on we find ourselves in a different harmonic context. Although the contra subject is the same as before (C-D-E in the cello), the subject is transposed up a fourth, starting on A. This suggests the key of d minor which is indeed supported by the notes in the violins (F and A). The second beat of m.6 is a passing chord from d minor to F major (m.7, first eighth note). The F natural does not occur in the bass (cello) but in the first violin.

The harmonic progression from m.7 to m.10 is a cadential progression to the III (relative major) of a minor: C major, which is reached on the first eighth note of m.10 and prolonged to the III6 on the third eighth note of that measure.

The progression is:

subdominant (F major, mm.7-8) – dominant (G major, m.9) – tonic (C major, m.10).

Therefore I made mm.7-10 a tonicization of the III of a minor (C major) and within that (mm.7-8) a tonicization of the subdominant of C major (F major).

Notice how Schumann in m.7 and m.8 uses the same subject (one octave apart) but harmonises it differently. In fact these measures are also a cadential progression to the F major chord on the second beat of m.8.

C major (the III of a minor) is not the end point of this phrase. The tonicization ends on the second beat of m.10 and the dominant of a minor follows (E major). I have interpreted m.11 as a kind of embellishing neighbour to the surrounding dominant chords. It is a VI of course but doesn’t have the function of a deceptive cadence. That being said the arrival on the dominant in m.12 is a half cadence (HC) which ends the first phrase.

Looking at the whole of the A part we see harmonically a tonic (a minor) – mediant (C major) – dominant (E major) progression. As was shown in the post on the piano quartet by Schumann he had in mind a division of time (past-present-future) which he mapped on the tonic triad. The quotes by Schumann that explain this idea can be found here. The harmonic progression of this first phrase fits seamlessly in this mental image.

The B part.

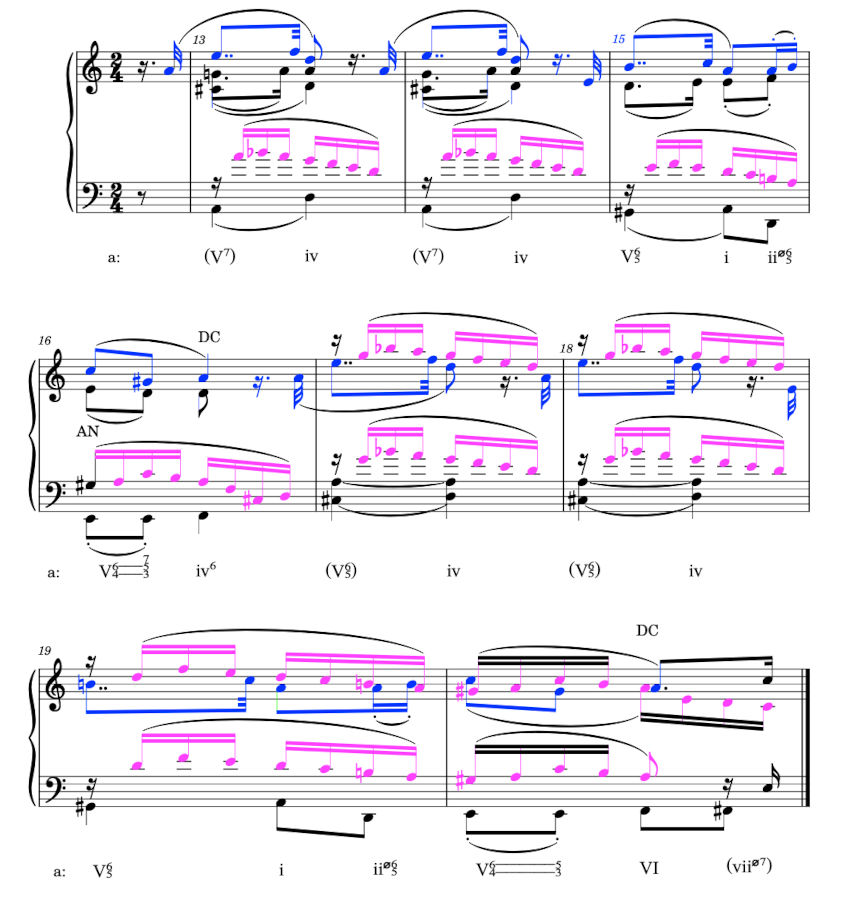

The B part starts in m.13 with an upbeat and is in the key of d minor (the subdominant of a minor). Harmonically the progression of m.12 to m.13 is not from the dominant E major to a minor as one might expect but to an A dominant seventh chord, which functions as the (applied) dominant of d minor. As mentioned the end of the B part is ambiguous: it is either m.24 or m.25. We’ll come to that. At the start of the B part a new motive is introduced which is presented in the form of a period (look here for my post on an introduction to the concept of period). Figure 1.3 shows this period.

fig.1.3 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, mm. 13-20

The new motive – played by the first violin – is shown in blue. The viola plays the fugue like subject starting on an A natural which fits with the key we are into: d minor. There is a small adjustment to make the motif fit into the harmony ending on the local tonic (d minor). This time it has an accompanying function, be it with a contrapuntal inclination.

The antecedent of the period runs from m.13 to m.16 (included) and has itself a bar form (a-a-b in the ratio 1:1:2). In m.16 it looks like the period will end on a minor because of the dominant seventh chord, preceded by the dominant six-four suspension in the first half of the measure, but as it turns out it is a deceptive progression. The chord on the second beat of m.16 is a iv (d minor) again but this time with a F natural in the bass. It is not the more common VI of a minor (F major) but the iv in first inversion (both chords having the 6th scale degree of a minor in the bass).

The consequent of the period (mm.17-20) starts with the same basic idea as the antecedent and so this is a parallel period. Notice that the motive is now played by the second violin and that the first violin joins the viola in the accompanying fugue motive, giving it more weight. This increases the contrapuntal character of the phrase. In m.20 there is again a deceptive progression this time actually leading to the VI of a minor (F major). So here it can be called a deceptive cadence (DC).

What follows in the next four measures is an internal extension of this period (figure 1.4), internal because there is no cadence at the end of the consequent.

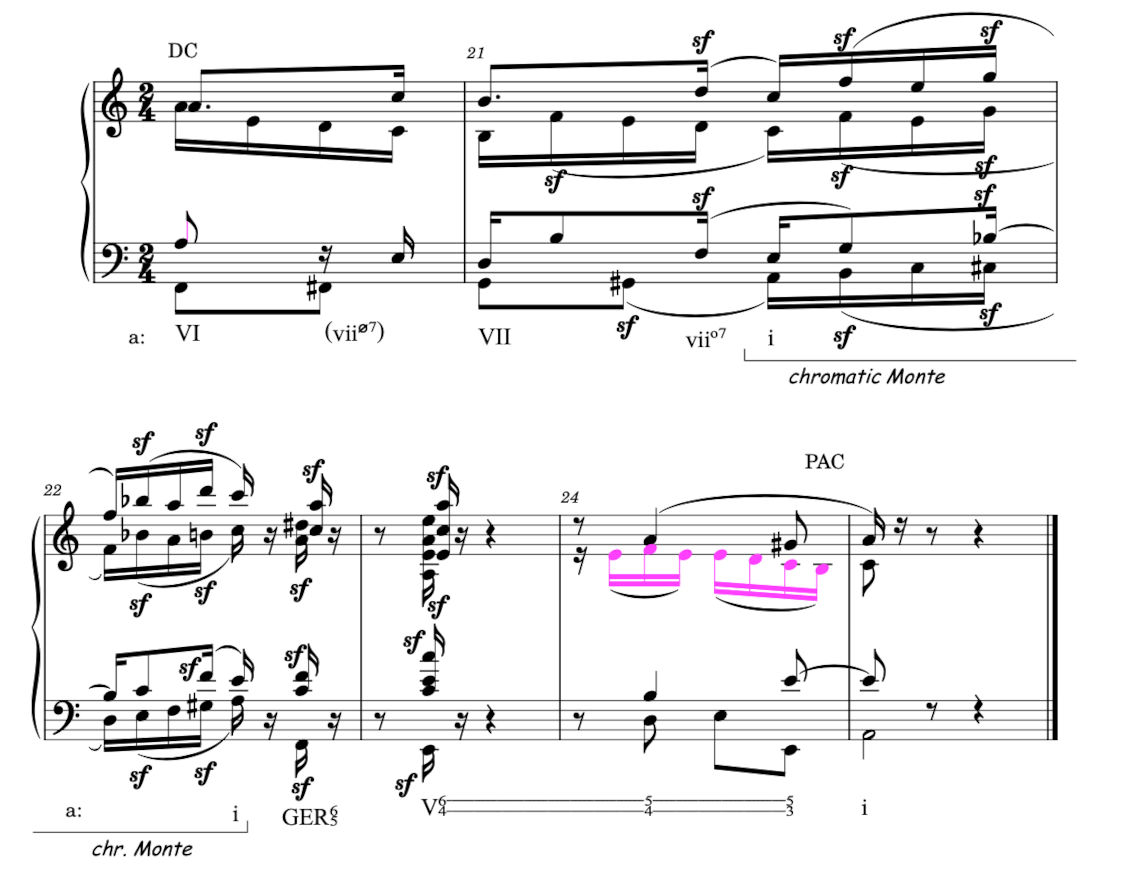

fig.1.4 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, mm. 21-25

This extension leads to a climax in m.23 and then a relaxation and solution in m.25. As shown before the period ends in a deceptive cadence in the second half of m.20. This asks for some form of resolution. Schumann first progresses chromatically from the VI in m.20 to the tonic on the second half of m.21. He does this with an well-proven method: stepwise diatonically (the VII and i) each of which is preceded by its applied seventh chord (last eighth note of m.20 and the fourth sixteenth of m.21). The tonic in m.21 is not the stable resolution we are expecting. It is not on a heavy beat and secondly the harmonic progression is not an authentic cadential one (vii0-i). On the second beat of m.22 there is again a tonic a minor chord (i) which is in fact a deferment of the previous one (but one octave higher), again not on a heavy beat and again with a vii0-i progression.

The chromatic Monte

Between these two tonic chords there is a rather chromatic progression which is very similar to a chromatic Monte. Schumann made a variation on one of the Galant schemata. What are Galant schemata? That is not so easy to explain but the following citation from a book by Job IJzerman might give you some clue:

The musical Galant style covers a large part of the eighteenth century, roughly 1720-1770, and is found in many European countries. The adjective “galant” literally means courtly, well-mannered. In this sense a galant person was well-educated, knew how to behave in social life, and had a considerable understanding of art and music. Galant music responds to these requirements, insofar as it implies a natural, relatively simple, and melodic style that resists the complex “learned” polyphony of the Baroque period. Moreover, galant compositions share a vocabulary of musical patterns and phrases that were easily comprehensible for a large group of musical amateurs.[6]Job IJzerman, Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 2018), 99.

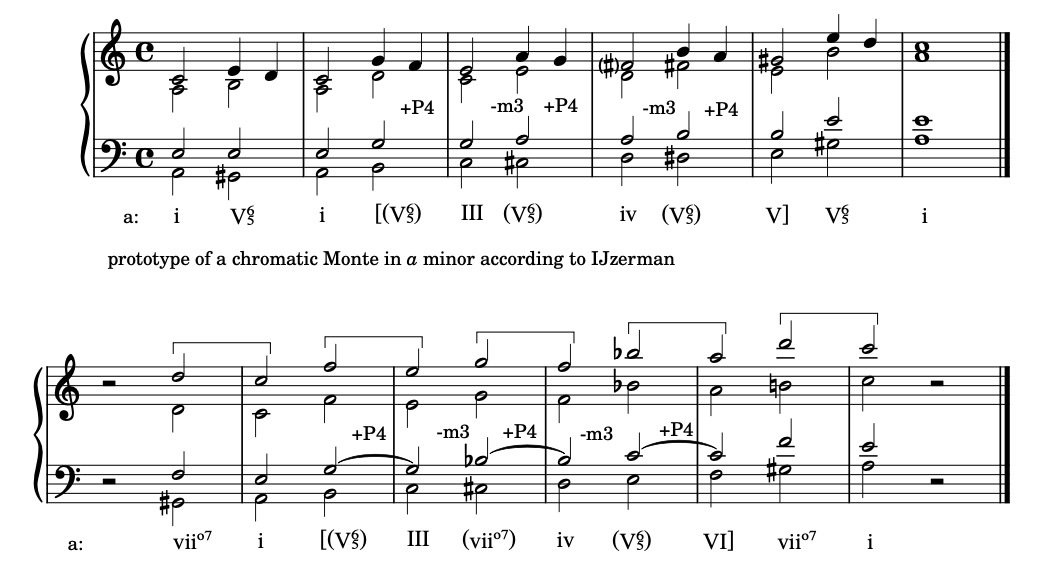

The Monte is one of these musical patterns that were used as standard formulas to put compositions together. Figure 1.5 shows the prototype of a chromatic Monte as presented by IJzerman[7]IJzerman, Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento, 216. and how Schumann’s harmonic progression in mm.21-22 can be mapped onto this.

fig.1.5 Schumann SQ no.1: variation on the chromatic Monte

A few remarks upfront:

- the second system represents m.21 second eighth note to m.22 third eighth note of the string quartet. The sixteenth notes have been augmented to half notes (minims) to match the IJzerman example

- +P4 means: a perfect fourth up (the chord, not the bass note)

- -m3 means: a minor third down

- the whole progression is an ascending second sequence A2(-3/+4), which is the essence of a Monte (see notational syntax in my post general notes on analysis for some explanation on sequences)

We can pick up the Monte on the second half of the first bar, both having a G-sharp in the bass. In the prototype this is a V65 chord. Schumann uses only three notes in the chord and this makes it an incomplete vii07 chord (g-sharp diminished without the B natural). This chord is comparable to a V65 because it can be seen as a V9 without the root (E natural). The violins play in octaves all the time, thus emphasising the diminished fifth in the seventh chord (or the seventh in the dominant chord). I suppose that is a matter of tone colour.

The a minor chord in the first half of the second bar is identical. The V65 chord in the second half of this measure is almost identical. Schumann is more sparing again and omits the fifth in the chord (the D natural). In the third measure the III is identical again and the applied chords to the iv show the same pattern as in the first measure: a V65 in the prototype and a vii07 chord in Schumann’s version. The same holds for the second half of the fifth measure and the sixth measure where the tonic a minor is reached again. In between there is a deviation between the two versions: the prototype goes to V in the fifth measure whereas Schumann uses a VI with its applied V65.

The conclusion is that Schumann pretty closely followed the Monte (or the A2(-3/+4) sequence) but made his own variation to shape the climax. Notice that there are numerous sforzandi almost always on the weak part of even the eighth notes (the applied dominant or seventh chords). This increases the shortness of breath to strengthen the building of the climax.

As already pointed out this a minor chord (m.22, second beat) is not the resolution of the phrase. In the same measure follows a GER65 (predominant) chord which starts – with the following suspension dominant six-four chord in m.23 and the slowly evolving dominant in m.24 – a stretched cadence. The tension is raised to a maximum by the pause between the chord in m.23 and the entrance in m.24: three eighth notes (three quarters of a full bar).

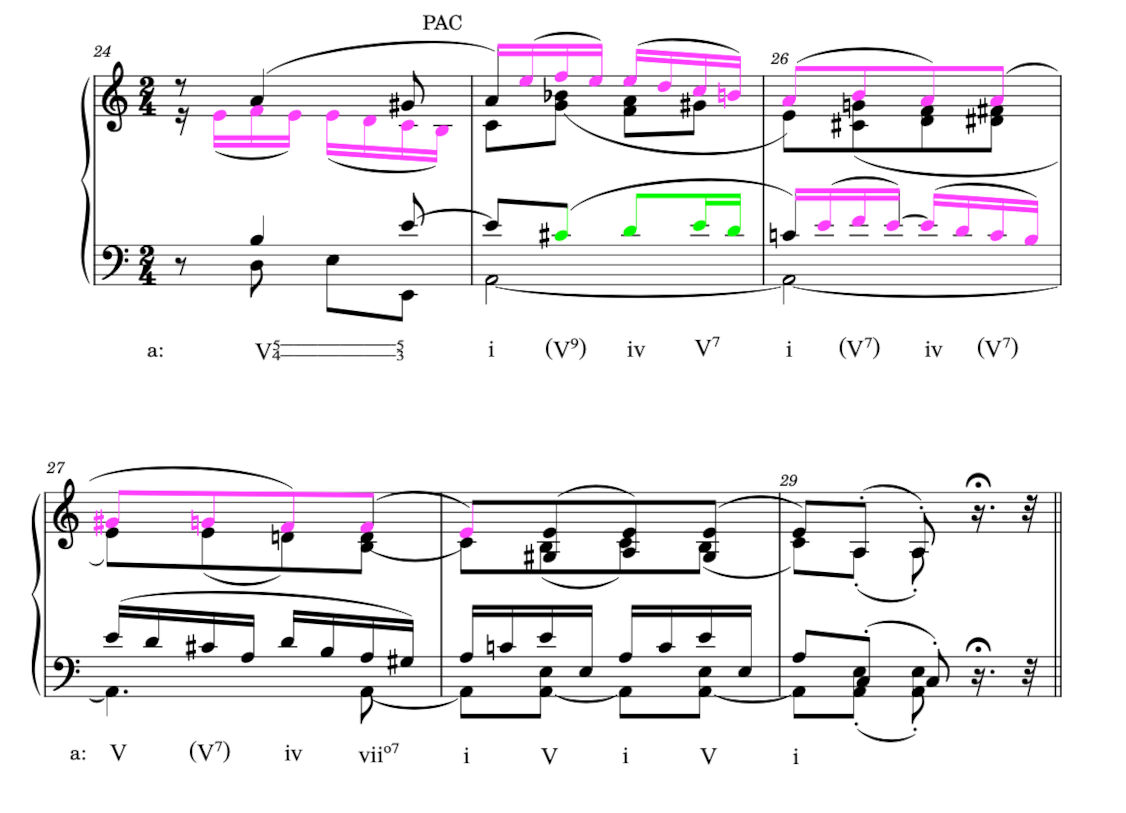

Now here is the point of the ambiguous ending of the B part. In m.24 the second violin starts the fugue motive which suggests the start of a new phrase. This is the approach along the form line. Harmonically however we are in the middle of a cadence which resolves only on the first beat of m.25 with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC). This is the process line of approach.[8]The distinction between form and process is explained in chapter IV, Hierarchic Structures in Leonard B. Meyer, Explaining Music: Essays and Explorations (Berkeley [etc.]: University of California Press, 1973). Schumann creates a beautiful tension between these two lines of approach and only in m.25 the listener feels at home with the harmonic resolution and (the repetition of) the fugue like subject.

The A’ part.

From m.24 onwards the initial motive returns more or less in its original shape (fig.1.6). The contra subject is missing although a reminiscence is found in m.25 in the viola (made green). An augmented version of the subject is found in m.26 to the first eighth note of m.28 in the first violin after which there is only a cadential progression left.

fig.1.6 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, mm. 24-29

Along the form line this phrase (mm.24-29) is a reduced version of the opening phrase and therefore I would say this can be addressed as A’. Harmonically there is first of all the pedal on A natural in the cello which pervades the whole phrase, strongly reminding us of the key we are in. On top of this pedal is a repeated cadential progression (iv-V-i) that reinforces the world of a minor. Not superfluous as we shall soon see.

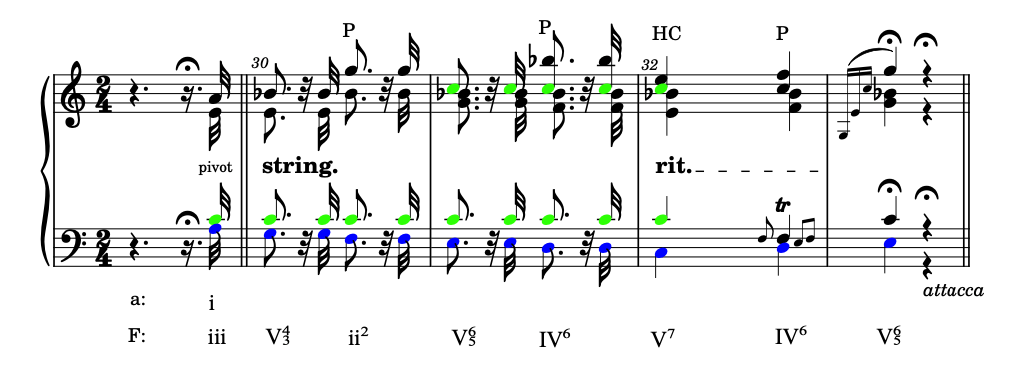

The B’ part.

Figure 1.7 shows the last four measures of the slow introduction. Perhaps first of all: why call this the B’ part? The B part is the period with the new motive (mm.13-20, fig.1.3). Very characteristic of the motive in the B part is the short upbeat (one thirty-second note). The same rhythm is found here, be it in a reduced form. We might call this a fragmentation of the motive in the B part (which is shown in blue in fig.1.3).

fig.1.7 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, mm. 30-33

So what is this short exiting phrase leading to the Allegro and why change to the key of F major? Well, the last one is easy: the Allegro is in F major (the submediant of a minor) and this phrase culminates in a weak kind of half cadence (weak because it is not in root position) in that key (m.33). The question is of course: why F major? If Schumann wanted to go to a major key for the Allegro, then the mediant C major (relative major of a minor) would have been quite an obvious choice but he chose the submediant. For me the submediant sounds not as brilliant as the mediant, so maybe Schumann wanted to stay closer to the colour of a minor. This is reinforced by the fact that the F major triad has two tones in common with the a minor triad. In the end I think we can only guess at the reason. Let’s call it an artistic choice.

Immediately in the upbeat to m.30 we find the change to F major. The a minor chord has a mediant function in F major and is thus a pivot chord. Subsequently there is a descending line in the bass from the third to the fifth scale degree, talking F major (cello, shown in blue). The viola plays a pedal on C natural (C natural being the dominant of F major, shown in green). The chord progression (which harmonises the descending bass line) is an alternating predominant – dominant one, in which the predominant chords function mainly as passing chords. The progression from the second beat in m.31 to the first chord in m.32 is a Phrygian half cadence; it is the only dominant chord in root position but it is not the end of the phrase. In the last two measures the bass starts ascending from 5 to 7 to reach the 1 on the first beat of the Allegro.

The exposition

The Allegro is in sonata form and the exposition contains the following elements:

Measure

34-75

76-100

101-136

137-150

Key (relative to F major)

I

I – V/V

V

V – I

Table 1: layout of the exposition

The main theme or First Tonal Area (FTA)

A downloadable PDF of the FTA in piano score format with my annotations can found here. The FTA can be analysed as having three parts, indicated by A1(mm. 34-49), A2(mm. 50-65) and A1’(mm. 66-75). One can discuss whether this is a ternary or a rounded binary form. It depends on the interpretation of the key of the A2 part.

The A1 part

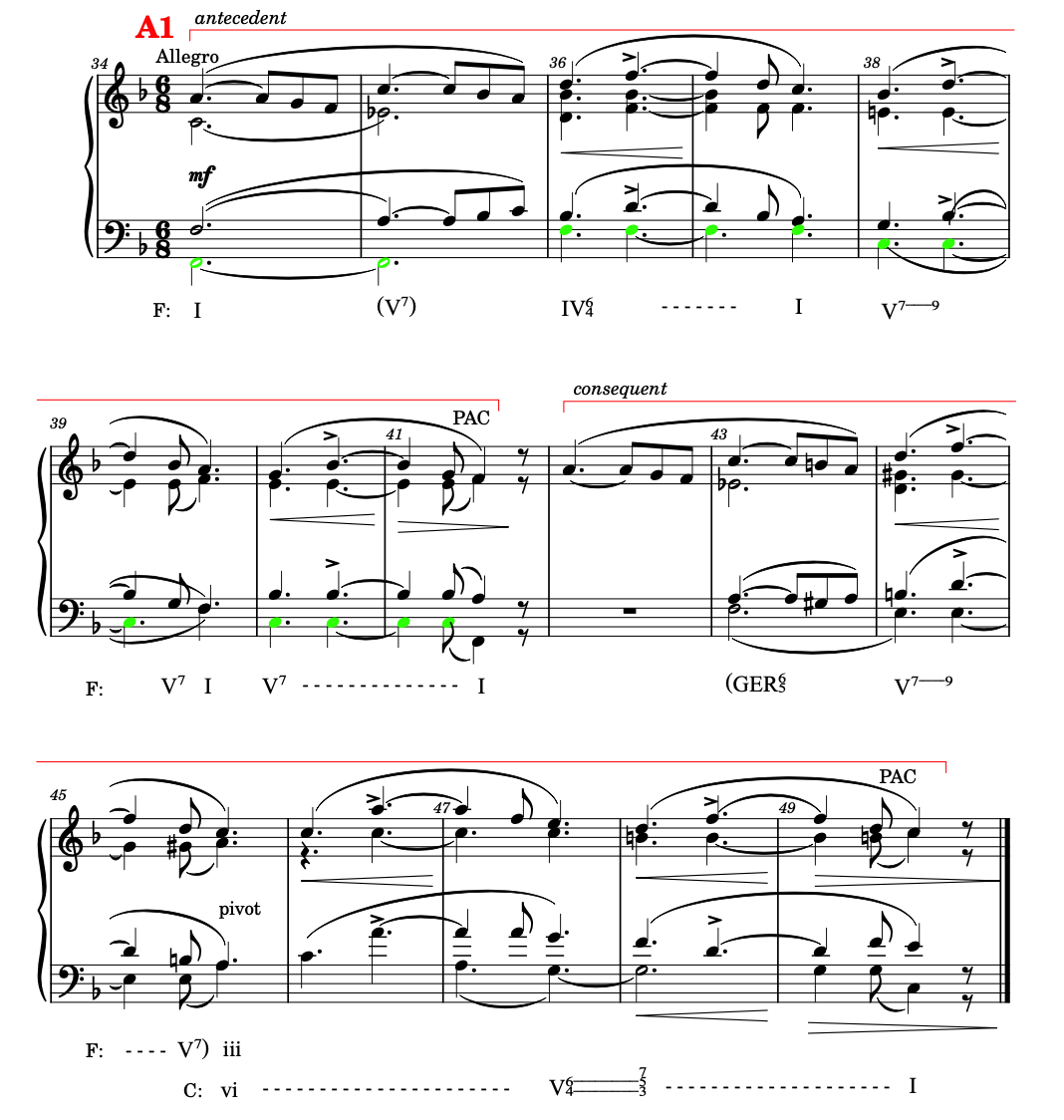

Figure 1.8 shows the A1 part. Clearly two eight bar phrases can be distinguished: mm.34-41 and mm.42-49. I think we can see this as a modulating period. The cadences that end the antecedent and consequent are equally strong, but in different keys. They are both perfect authentic cadences (PACs, m.41 and m.49 respectively).

fig.1.8 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, mm.34-49

The basic idea of the antecedent (mm.34-37) is repeated in the consequent (mm.42-45) so this is also a parallel period (see my post on periods for an explanation).

Could the first phrase (antecedent) in itself be seen as a period? Not really, because there is no cadence at the end of m.37 and no repetition of the basic idea in mm.38-39. This phrase resembles mostly what Caplin would call a compound basic idea + continuation.[9]William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998), 61. That is to say: an antecedent without a cadence; basically it is a prolongation of I, reinforced by the prolonged F natural in the bass. The continuation is in this case a cadential progression (mm.38-41) mostly supported by a C natural in the bass.

For the consequent holds the same be it that it starts modulating at in m.43. The first aim is the a minor chord in the second half of m.45. It is the pivot to C major. Schumann starts the modulation with a dominant seventh chord on the tonic (F7, m.43), but this should be reinterpreted as an augmented sixth chord in a minor (GER65). Therefore we have to spell the E-flat as a D-sharp (the raised fourth scale degree in a minor). The chord functions as a predominant to a minor.

The A2 part

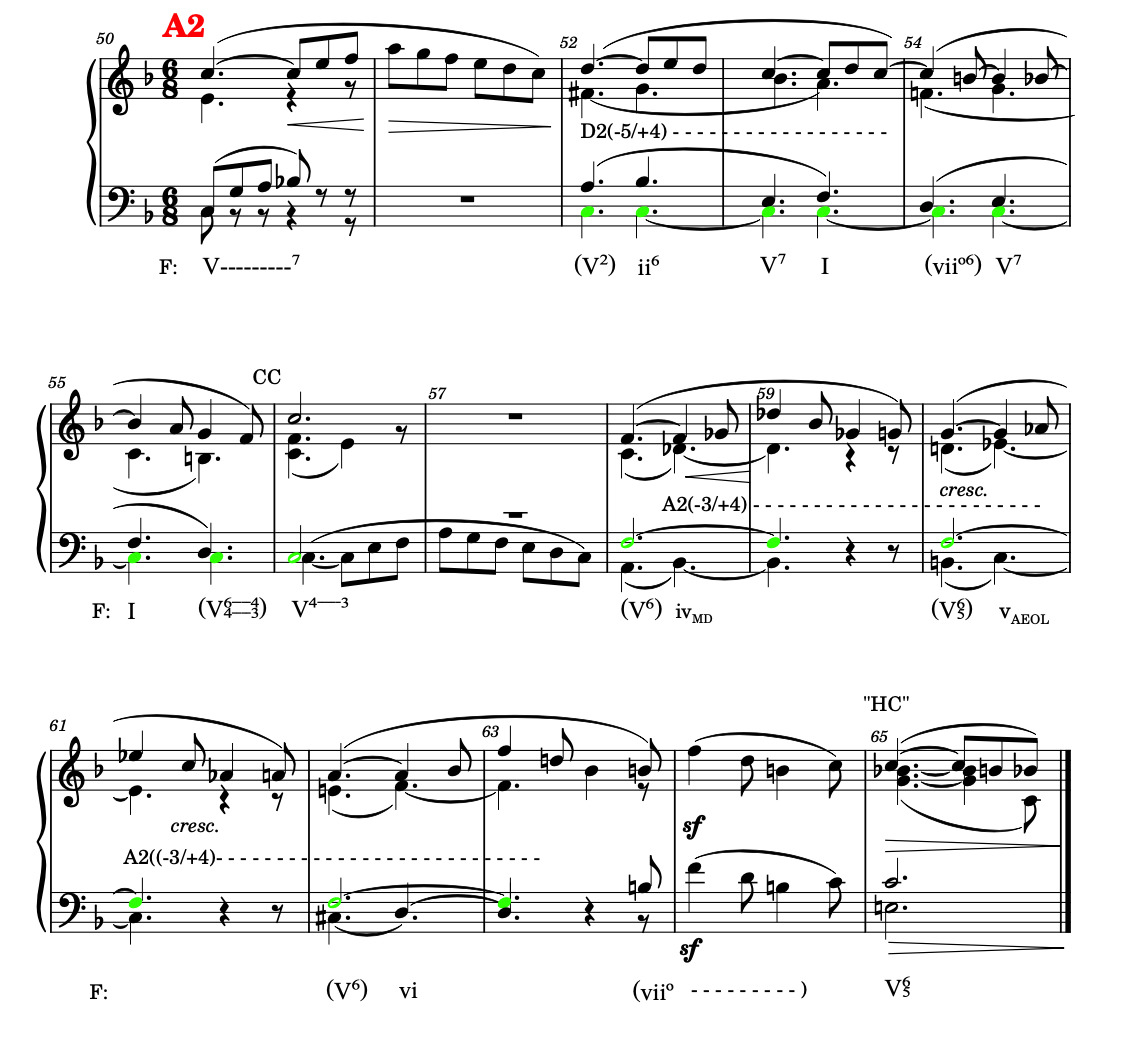

Figure 1.9 shows the A2 part. In the A2 part we can again distinguish two phrases: mm.50-56 and mm.56-65. Notice the overlap in m.56; it is the end of the first phrase and the start of the second. This division results in an asymmetric form with a seven bar first phrase and a ten bar second phrase. Because of the overlap in m.56 the total equals 16 measures.

fig.1.9 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, mm.50-66

The first phrase starts in C major (m.50) but immediately moves to F major, which is followed by a falling fifth sequence (D2(-5/+4)). The sequence starting in m.52 is:

D7– g minor – C7– F major – b0

The last chord has the function of a diminished seventh to C7 which leads to F major on the first beat of m.55 after which a cadence with some suspensions in C major follows. In the first phrase we have a pretty strong C major feeling, corresponding to the classical rule that middle parts of a ternary form in major tend to have the dominant as key. This is reinforced by the C natural pedal in the cello (shown in green). Nevertheless the chord on the second half of m.52 (g minor) has a strong F major tendency as it can more easily be interpreted as a ii in F major than as a vAEOL in C major, so I chose to analyse the whole phrase in F major.

The second phrase starts with the same motive in the cello (mm.56-57) and then an ascending second sequence follows: A2(-3/+4). This can again be seen as a chromatic Monte. The sequence starting in the second half of m.58 is:

b-flat minor – G65 – c minor – A major – d minor – b0

This sequence has one step (and two bars) more than the previous sequence. This explains why the second phrase is longer then the first phrase. Again the last chord has the function of a diminished seventh to C7 which leads to a kind of half cadence (HC) in m.65. A kind of, because the chord is not in root position. Notice the similarity with the end of the slow introduction (fig.1.7).

The whole of the A2 part is quite ambiguous in terms of key. Is it C major or F major? It is one of the trademarks of Schumann (see also the second part of the exposition of the piano quartet). As the beginning has a strong tendency towards C major, even if analysed in F major, I conclude that the form is ternary and not rounded binary.

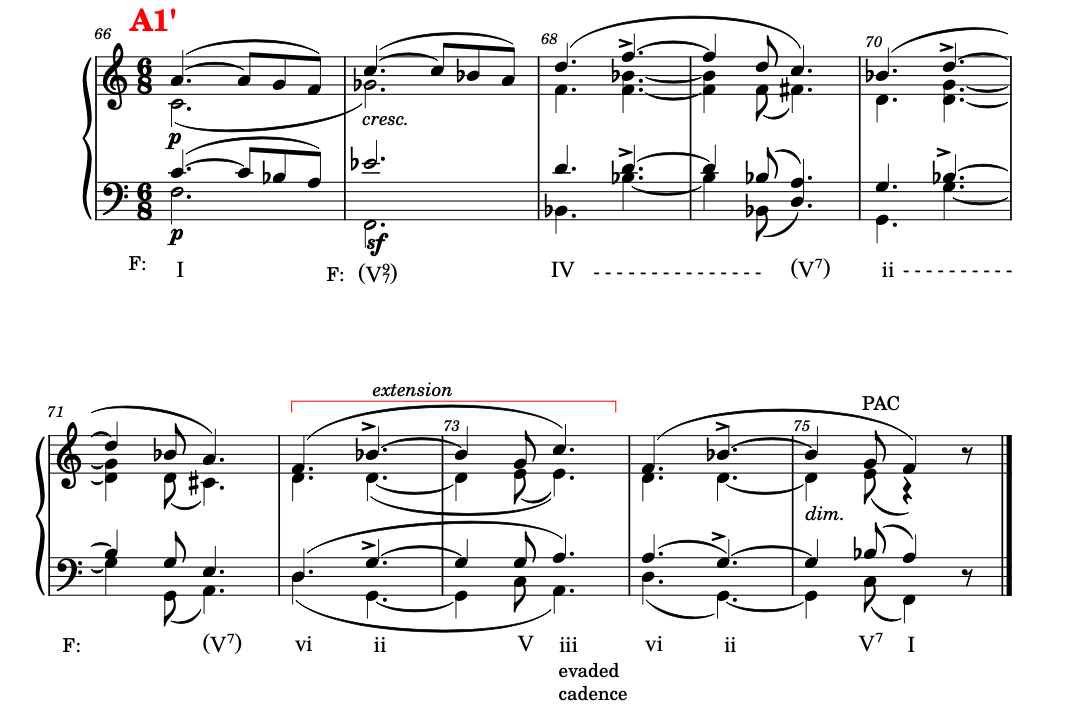

The A1’ part

Figure 1.10 shows the A1’ part. This is a ten bar phrase and in fact very similar to the antecedent of the A1 part (therefore it is called A1’). There are differences however.

fig.1.10 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, mm.66-75

The first thing to notice is the number of measures. A1’ has ten bars whereas the antecedent in A1 has eight bars. The extra measures can be found in mm.72-73. It is a cadential progression which ends with an evaded cadence in the second half of m.73 on a iii (a minor) chord. It is an internal extension. After this the phrase ends with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in F major.

The melody in the soprano (first violin) is exactly the same in the first six measures as the melody in the antecedent. After this the melody is adapted to the harmonic progression, first the deceptive progression in mm.72-73 and then the final cadence in mm.74-75.

To start with the final cadence: in mm.40-41 (fig.1.8) this is a V7 – I progression whereas in mm.74-75 it is a vi-ii-V7-I progression. So the harmonic rhythm in the last cadence is faster and more elaborate, giving it the character of a firm closure.

There are other things to notice: the chord in the second measure of the A1’ part (m.67). It is an applied dominant ninth chord for IV with a lowered nine. Quite a special colour! And the end of the fourth measure (m.37) is in the A1 part a tonic I whereas in the A1’ part the final cadential progression has started with an applied dominant to ii (second half of m.69).

So the A1’ part is a repetition of the opening of the main theme and as the period in the A1 part is parallel (repeating the basic idea in the consequent) the consequent is left out here; only the essence is repeated, be it with a small extension.

The motives of the main theme

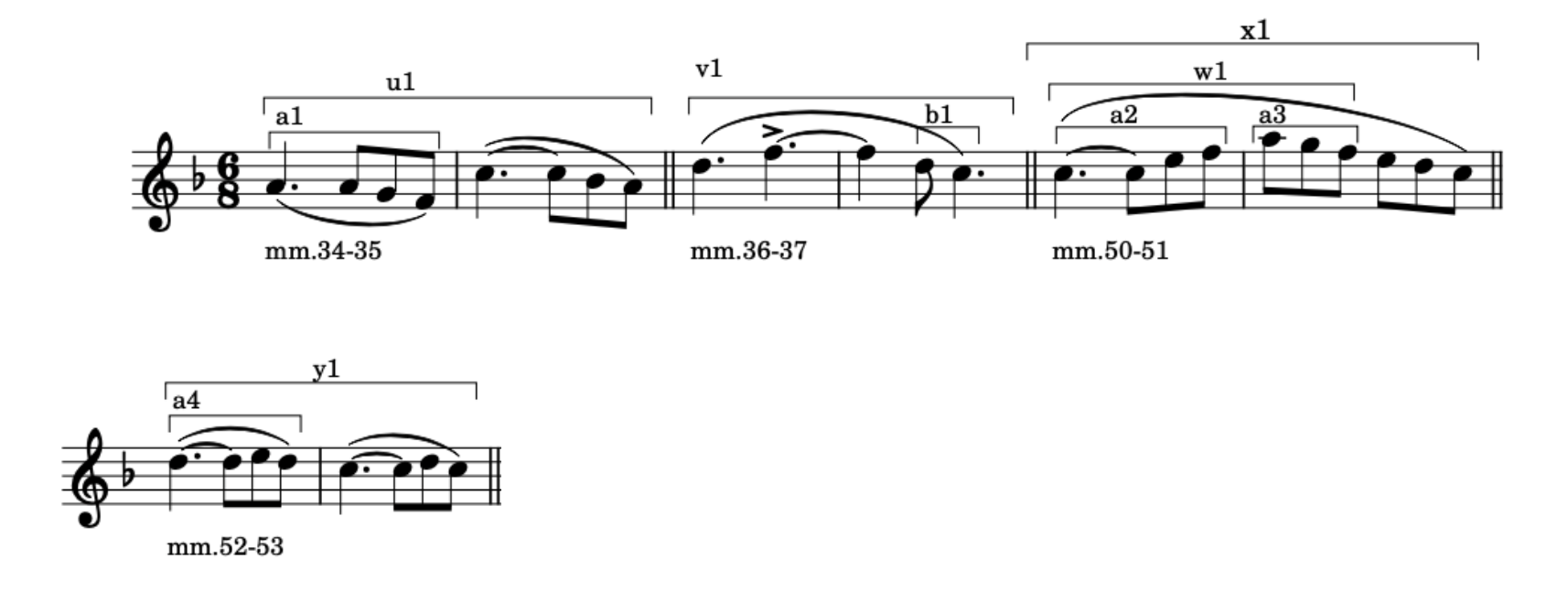

A last thing to discuss are the motives used in this first tonal area (FTA). Figure 1.11 shows these motives.

fig.1.11 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, motives of the FTA

The motives a1, u1 and v1 are used in the A1 and A1’ parts, the a2, a3, w1 and x1 motives in the A2 part. Looking first at the a-family of motives we see that a2 and a4 are rhythmically identical to a1. The motive a2 has an opposite direction of the last two notes and the first interval is different. Nevertheless the kinship is evident. The motive a4 has a neighbour note in stead of a passing note and prolongs in fact the note with which motive starts.

The motive a3 varies another parameter of the motive a1: the rhythm. Melodically it does the same as motive a1 (stepwise descending) but the first note is reduced to an eighth note.

The motives u1, v1, w1, x1 and y1 are compound motives. u1 steps up the F major triad, w1 ascends on the F major triad and goes stepwise down and y1 descents stepwise with the neighbour note embellishment on the fifth eighth note.

The v1 motive is the most used motive. Looking at the antecedent of the A1 period (mm.34-41) the v1 motive is the contrasting idea in the compound basic idea. The continuation (mm.38-41) consists of two more occurrences of this motive. This is repeated in the consequent and once more in the A1’ part. All in all ten occurrences of this motive.

This completes the analysis of the first tonal area (FTA).

The Transition (TR)

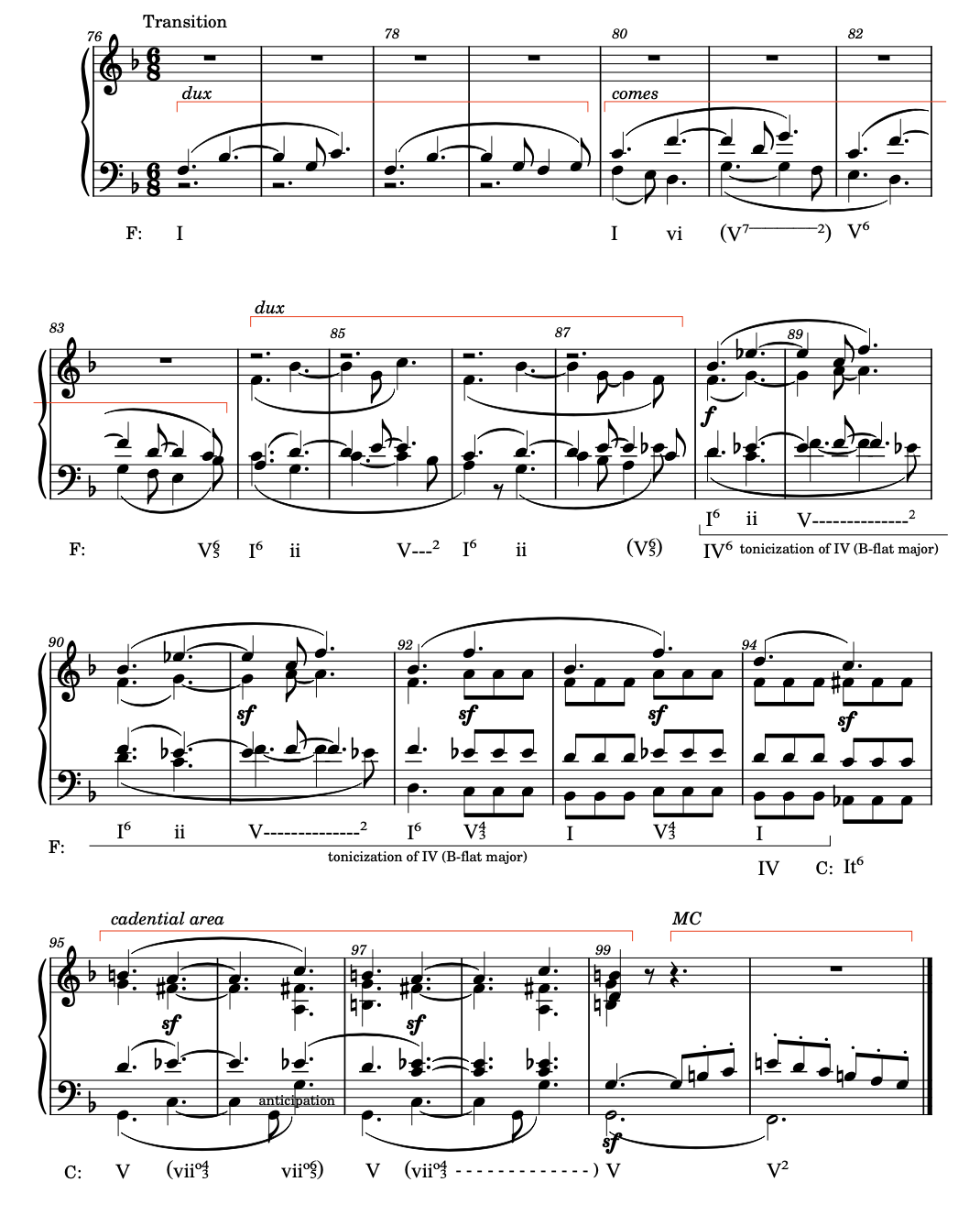

The next section is the Transition (TR) which links the main theme to the subordinary theme. It is evidence again of the effect of Schumann’s exercises in counterpoint and fugue. It is 26 measures long and figure 1.12 shows a piano score version.

fig.1.12 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, mm.76-100

Harmonically the function of this section is to make the transition from the key of the main theme to the key of the subordinate theme (F major and C major respectively). In a minute I will explain how Schumann did this but first of all it is noteworthy to look at the form and the way the motivic material is used.

The Transition: form and motives

The phrase structure is as follows: four four-bar phrases (the first three of which are labelled dux–comes–dux). These sixteen bars are in fugato form, i.e. fugue like but not completely compliant with the rules of the fugue. Then follows a three bar connecting phrase (mm.92-94), then again a four bar phrase and the transition ends with one and a half bar labelled MC (medial caesura).

The first four bar phrase (dux, mm.76-79) has two variations of the v1 motive (which will be called v2 and v3, fig.1.13). The second four bar phrase (comes, mm.80-83) starts with the v2 motive but ends with yet another variant of the v1 motive: v4. Figure 1.13 shows all the motives up to the second tonal area (STA). Notice that all variants of the v motive (except v1) start with an ascending interval of a fourth but in the second bar of the motive the variations take place.

fig.1.13 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, motives up to the STA

The third four bar phrase (mm.84-87) equals the second one. As already mentioned I labelled the first three phrases in a fugue like way. This is almost correct because the theme – or subject in fugue terms – is almost identical. The entrances of the duxes and comes are completely in accordance with the fugue form: the dux starts on the tonic and the comes on the dominant. So apart from the ending of the first dux these first three entries comply to the fugue rules.

From the fourth entry onwards Schumann leaves the fugue model. The subject is repeated once more in the first violin (mm.88-91) but this time in B-flat major (the subdominant of F major). The motive used is two times the v2 motive. This is yet another variant of the subject. After this follow three connective measures mainly prolonging the B-flat harmony (mm.92-94). Then another variant of motive v (v5) returns in the cello (mm.95-98). After that two connecting measures follow before reaching the second tonal area (STA) in m.101. In the two connecting measures (mm.99-100) the viola plays a variant of the x1 motive. These measures are on the spot where the medial caesura can be expected. Let’s name them that way: a medial caesura with a caesura fill in the viola, cello and second violin (see my post General notes on analysis for some explanation). The x2 motive foreshadows the rhythm and articulation used in the subordinate theme or second tonal area (STA).

The Transition: harmonic progression

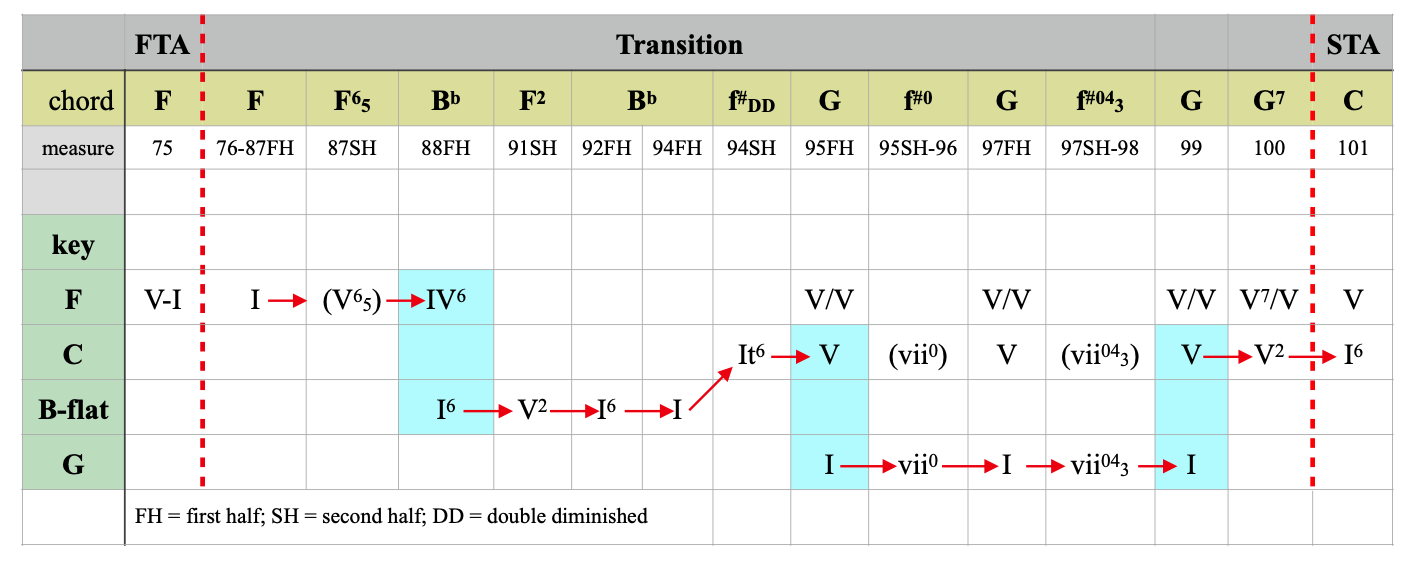

What is left to discuss is the way in which Schumann made the harmonic transition from F major to C major. Figure 1.14 shows a diagram of this transition.

fig.1.14 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, levels of analysis in the transition

This diagram tries to explain how you can look at different levels of analysis at the chord progression in a certain section of a piece. In this case these levels are:

- the level of the exposition (and in fact of the Allegro as a whole)

- the level of the various components within the exposition (FTA, Transition, STA, Closing Section)

- the level of segments within these components (for instance a cadential area).

The keys as mentioned in the first column of the diagram correspond to these levels as follows:

- F major, as the key of the Allegro, and the key of the component first tonal area (FTA)

- C major as the key of the component second tonal area (STA)

- B-flat as a segment within the Transition; G major as the key of the cadential area within the Transition

Whereas the choice of key for the Allegro is unusual, the choice for the key of the second tonal area (STA) is quite conventional (or classical): the dominant of F major, C major (reached in the utmost right column).

The chords as encountered in the transition are shown in the second row and the third row gives the measure(s) in which they are found. The cyan coloured cells in a column mean that a chord can belong to more than one key; they can be used as a pivot chord to go from one key to another. For example look at the first G major chord in the second row (m.95 first half). At the level of the STA (key: C major) it is a dominant (V) but at the level of the cadential area (key: G major) it is a local tonic (I). At the level of the exposition (key: F major), G major is the dominant of the dominant (V/V), also shown in the diagram. The partial cyan columns are a sort of elevator to go from one key to another. The red arrows, together with the elevators, lead you through the harmonic progression.

I will help a little bit. Measure 75 is included in the diagram to show the connection between the main theme (FTA) and transition. In fig.1.10 one can find the final cadence in the tonic (I:PAC) of the FTA in m.75. In the diagram it is the V-I in the second column.

The transition begins in the tonic F major. It is the very fugue like part which is harmonically a prolongation of F major (mm.76-87). In the second half of m.87 there is a F major chord with an added seventh so it becomes an applied dominant of B-flat major, the subdominant of F major.

The next six and a half measures (mm.88-94 first half) reside in B-flat major, the subdominant of F major. As mentioned before I made it a tonicization in B-flat. A logical continuation would be to proceed from the predominant to the dominant of F major (C major) and then back to the tonic F major again. But that is not the goal Schumann is aiming for. Perhaps he is suggesting it with the prolonged B-flat major, but he is misleading us. He wants to go to C major, but not as the dominant of F major but as the new (local) tonic centre of the second tonal area. Here we see clearly the different levels of analysis. On the first level C major is of course the dominant of F major, the tonic of the Allegro. But one level lower – of the main and subordinate theme – C major becomes the local tonic and deserves to be modulated to.

So Schumann does not proceed from B-flat to C major (predominant – dominant), but inserts an augmented sixth chord (the double diminished f-sharp chord in first inversion, an Italian sixth chord) in the second half of m.94. It functions as a predominant of C major and the dominant follows in m.95. So this should be regarded on the second level, that of the local tonic of the second tonal area (the row with the C major key).

Before reaching C major there is a cadential area (mm.95-99) in which we experience the key of G major. So on level 3 of the analysis (the cadential area) G major dominates with its own seventh chords (the f-sharp diminished chords in mm.95-96 and mm.97-98). One level higher G major is the dominant of the local tonic of the second tonal area (STA) and still one level higher it is the dominant of the dominant (V/V) of F major. All these levels are shown in the diagram.

The first inversion of C major is finally reached in m.101, by way of a descending bass line G-F-E, harmonised with V-V2-I6. Measure 101 is the first measure of the second tonal area (STA).

The Second Tonal Area (STA) or subordinary theme

As shown in table 1, the STA runs from m.101 to m.136. A downloadable PDF of the STA can found here. The key is quite classical C major, the dominant of F major. The subordinary theme is loose in form. The structure on the highest level is as follows:

Measure

101-117

117-124

125-137

comment

an ascending second sequence [A2(-3/+4)]

descending second or falling fifth sequence [D2(+4/-5)]

cadential area

Table 2: layout of the second tonal area or subordinate theme

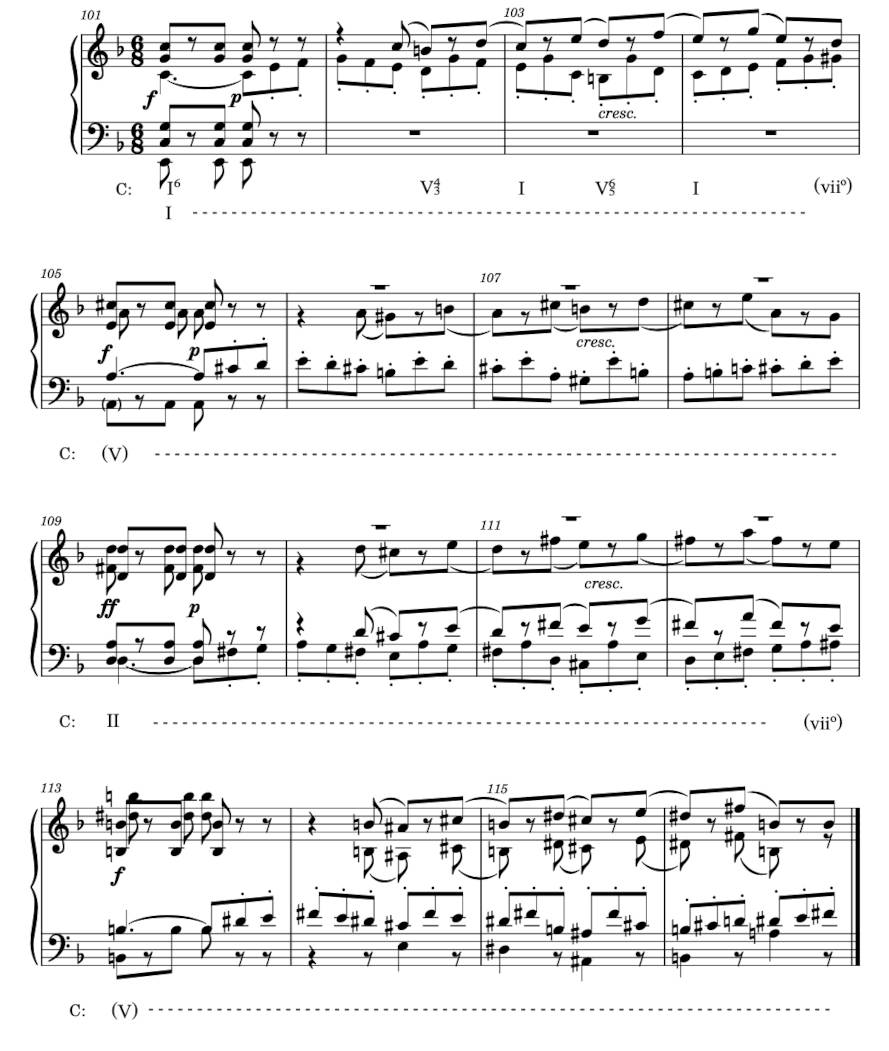

First segment of the The Second Tonal Area (STA)

Figure 1.15 shows the first section consisting of four phrases, each four bars long.

fig.1.15 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, mm.101-116

The keys of the phrases are: C major – A major – D major – B major (and e minor in m.117, not shown in this figure). This is an ascending second sequence [A2(-3/+4)] from C major to the third scale degree e minor with the applied dominants (A major [mm.105-108] and B major [mm.113-116]) in between. This clearly resembles a Monte except that the chord on the second scale degree is major (II, D major, m.109) and is experienced as a surprise as it does not fit diatonically in the scale of C major. The chord on the third scale degree is minor (iii, e minor, m.117) which fits in the scale of C major. So Schumann is (once more) playing with the concept of the Monte (or if he was not aware of this concept, with an ascending second sequence). Again by way of a seventh chord on the leading tone (m.112, last eighth; a very incomplete vii0 of B major), the applied dominant of e minor (the mediant of C major) is reached: B major (m.113).

Whereas in the classical style subordinary themes were often more lyrical than the main theme, that is clearly not the case here. The subordinary theme opens with a firm statement in forte (m.101), and continues with a sighing ascending phrase over a staccato accompaniment which crescendos to the next statement (m.105). The sighing motive is a variant of the b1 motive as shown in fig.1.11.This culminates in the high point of this first section: the surprising D major in fortissimo (m.109).

As already mentioned the form is loose and the motives used are closely related to the motives of the main theme. This is also true for the motives in the second segment. This is why Daverio refers to the first movement as monomotivic, another analogy with Haydn in dealing with the sonata form.[10]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 251.

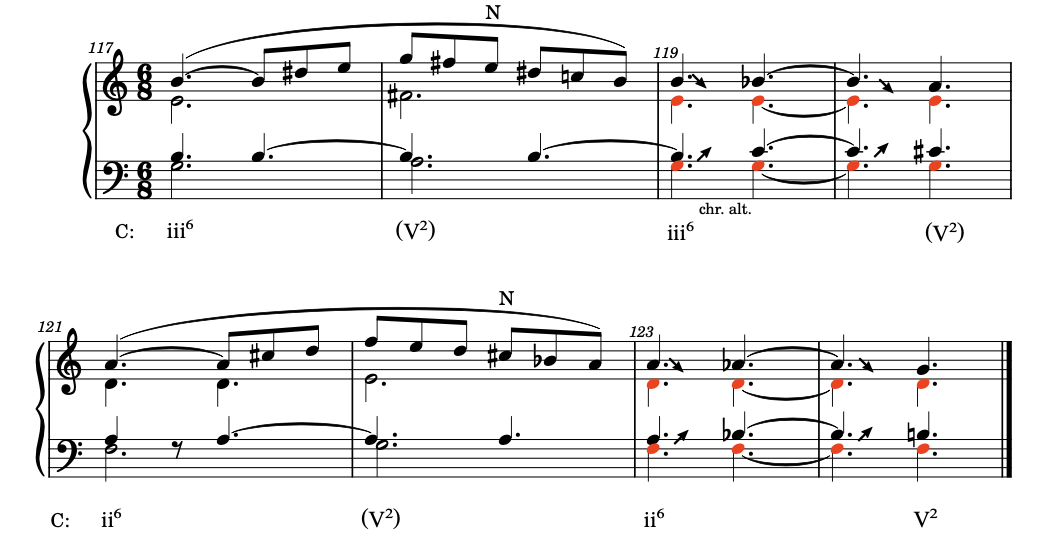

Second segment of the The Second Tonal Area (STA)

Figure 1.16 shows the second segment of the STA.

fig.1.16 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, mm.117-124

Here Schumann returns to the w1 motive (mm.117-118), first encountered in the A2 part of the main theme (fig.1.9). It starts on a e minor chord, the end point of the ascending sequence of the first segment. The e minor is again found in m.119 and in between (m.118) there is a B dominant seventh harmony in two position. It functions both as the dominant seventh chord of e minor and as a neighbour chord. The same holds for mm.121-123 with respect to d minor, m.122 being a A dominant seventh chord in third inversion.

The mm.119-120 and 123-124 have the same harmonic structure. They function as a transition. In mm.119-120 the transition is from e minor to A major. Schumann does this by way of two common tones (E in the second violin and G in the cello) whereas the first violin and viola make a chromatic descending respectively ascending motion. The chord in the second half of m.119 is therefore a passing chord. In mm.123-124 the transition being made is from d minor to G major.

The whole progression in the second segment is a descending fifth sequence [D2(+4/-5)]: e-A-d-G-C. The C major chord is reached in m.125, not shown in this figure. Notice that whereas in the ascending sequence (mm.101-116) occurs the surprising D major chord, here in the descending sequence Schumann uses d minor.

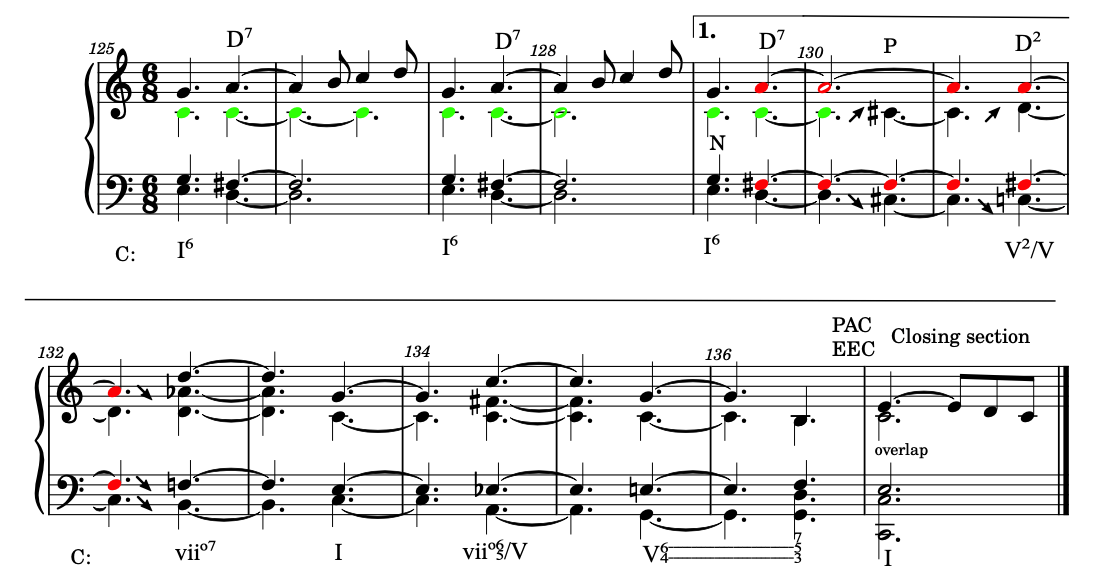

Third segment of the The Second Tonal Area (STA)

The last section of the STA is the cadential area in which C major for the first time occurs in root position (m.133) and is confirmed with a pretty strong cadence (mm.136-137). But before we reach that point Schumann has a another surprise for us (and again it is D major). Figure 1.17 shows the last segment.

fig.1.17 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, mm.125-137

In m.125 C major is reached again, in sixth position as in m.101, the beginning of the second tonal area (fig.1.15). What follows is a D7 chord. Trying to give this chord a function in a C major context one expects G major as the dominant of C major. But that is not what happens. After one and a half measure of the D7 chord there is again a C major chord in first inversion (m.127). The D7 chord functions as a neighbour chord to C major. This is repeated once more and then there is again a chromatic transition (starting in m.129), this time from D7 to D2. It is the same chord in a different position and Schumann realises this by means of voice exchange between the second violin and cello. The common tones are A (first violin) and F-sharp (viola).

This time the D2 chord does lead to a dominant chord of C major, be it one without the root; it is the b diminished chord in the second half of m.132. So in retrospect one can understand that the D7 chords were in fact a foreshadow of the dominant of the dominant function, but two attempts are needed before the cadence bursts out.

In m.133 C major in root position follows and then a full cadential progression leads to the EEC: the essential expositional closure in terms of Hepokoski and Darcy.[11]Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 18. It is in fact the first perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in the new key (to be understood as the key of the second tonal area). In this case you might think it is not a PAC as the note in the soprano (first violin) is not the tonic. I choose to say that the E in the first violin belongs to the things to come in the closing section and the final chord of the STA is only played by the other voices. In that case the cadence is perfect. Either way, m.137 is an overlap between the STA and the closing section.

As has been shown Schumann uses a rather free form for the second tonal area. It starts with a long standing sequence of 16 measures.

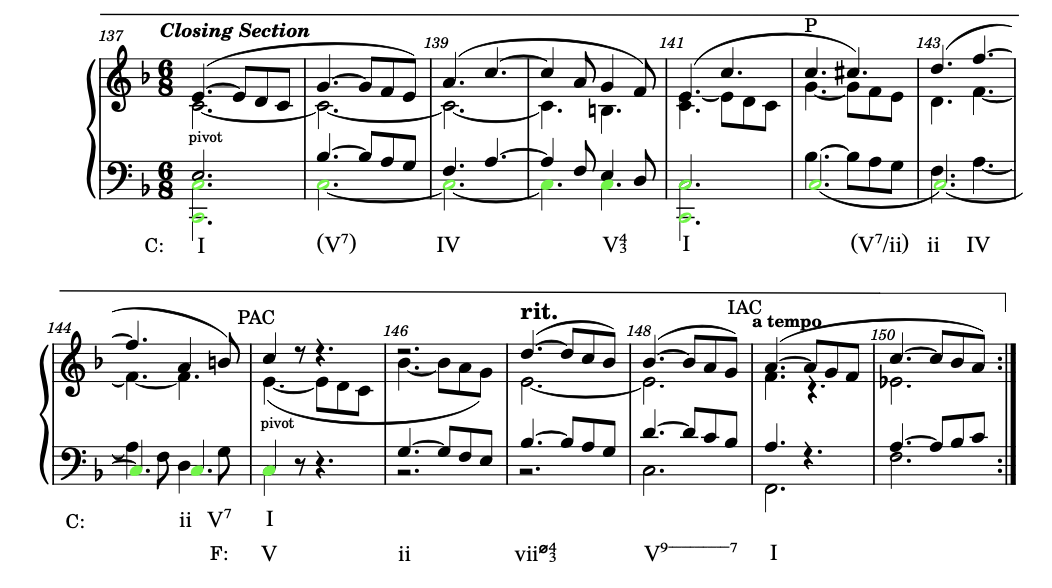

The Closing Section

The last part of the exposition is the closing section, according to Caplin a group of codettas following the subordinate theme (or second tonal area).[12]Caplin, Classical Form,16 and 122. In this closing section we can indeed distinguish three phrases of four bars each using the main theme as melodic material. Figure 1.18 shows the piano score of this section.

fig.1.18 Schumann string quartet op.41 no.1, i, mm.137-150

Laitz says that “the closing section’s purpose is to reinforce the new key [again: that is the key of the second tonal area or subordinate theme]”.[13]Laitz, The Complete Musician, 636. The first phrase or codetta (mm.137-140) is a prolongation of C major. It ends with a weak cadential progression and the motives used are those of the main theme, u1 and a variant of the v motive. Notice that the viola plays the same motive as the first violin, a1.

The second codetta (mm.141-145) ends with a full cadence in C major. The taste of F major however is already tangible because of the high F in the first violin. The harmonies up to the cadence resemble the ones in the first codetta. Added is the ii in m.143 with its applied dominant in the second half of m.142. The C dominant seventh chord (m.142, first half) is still the applied dominant of IV, but functions here as a passing chord to the A dominant seventh chord in the second half of that measure.

The mm.149-150 are in fact the same as mm.34-35 and belong to the repetition of the exposition. So a bridge is needed to F major (as this is the key of the first theme). That is the function of the last codetta (mm.145-148). In m.145 the function of the C major chord changes back to the dominant of F major and a cadence in F major follows.

Notice that in m.149 Schumann leaves out the C in the second violin (as in m.34, fig.1.8) to emphasise the key of F major as opposed to C major.

This concludes the analysis of the exposition of Schumann’s first string quartet. Two more to go.

Notes

| ↩1 | John Daverio, Robert Schumann: Herald of a “New Poetic Age” (New York etc.: Oxford University Press, 1997). |

|---|---|

| ↩2, ↩10 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 251. |

| ↩3 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 242. |

| ↩4 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 243. |

| ↩5 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 244. |

| ↩6 | Job IJzerman, Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 2018), 99. |

| ↩7 | IJzerman, Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento, 216. |

| ↩8 | The distinction between form and process is explained in chapter IV, Hierarchic Structures in Leonard B. Meyer, Explaining Music: Essays and Explorations (Berkeley [etc.]: University of California Press, 1973). |

| ↩9 | William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998), 61. |

| ↩11 | Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 18. |

| ↩12 | Caplin, Classical Form,16 and 122. |

| ↩13 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, 636. |

Recent Comments