Last updated on May 4th, 2025 at 12:06 pm

List of Abbreviations

AC

AEOL

AIN

AP

b.i.

appogg

CC

CF

chr. alt.

CL

CT

DC

DTr

D

EC

EEC

fb

FTA

HC

HK

IAC

IAN

IN

ITr

MC

M.T.

N

P

PAC

PD

PED

sb

STA

sus

T

Tr

VA

authentic cadence

Aeolean

accented incomplete neighbour note

accented passing tone

basic idea

appoggiatura

contrapuntal cadence

caesura fill

chromatic alteration

closing section

common tone

deceptive cadence

dependent transition

dominant

evaded cadence

essential expositional closure

first beat

first tonal area (also called: main or primary theme)

half cadence

home key

impecfect authentic cadence

incomplete accented neighbour note

incomplete neighbour note

independent transition

medial caesura

main theme (also called FTA or primary theme)

neighbour note

passing note or chord/Primary theme (depending on the context)

perfect anthentic cadence

predominant

pedal note or chord

second beat

second tonal area (or: subordinary theme or secondary-theme zone)

suspension

tonic

transition

a V that is an active chord, not a key; the A stands for “active”; the dominant is not tonicized; instead it implies a resolution to the tonic[1]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, xxv.

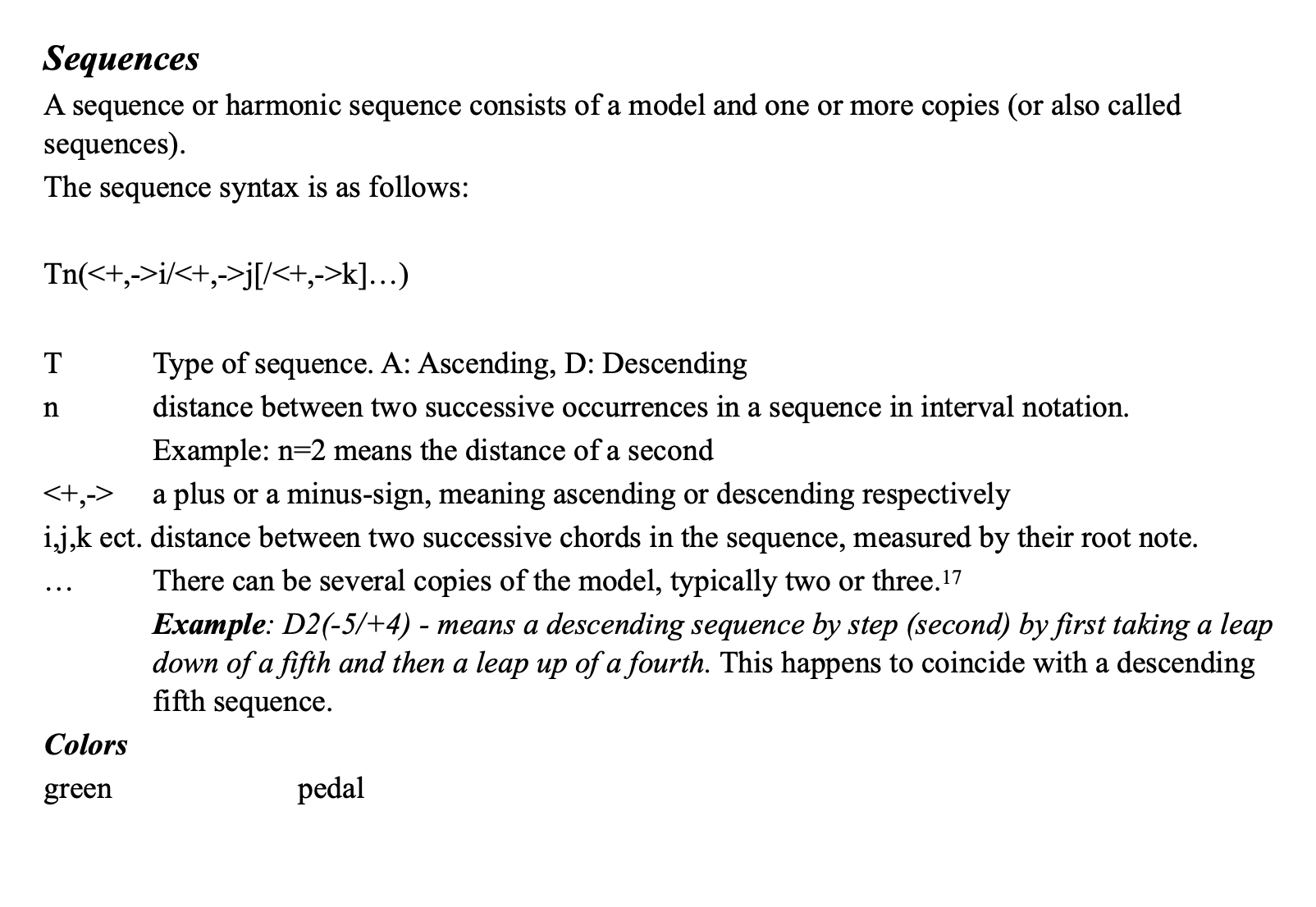

Concepts

Authentic Cadence (AC)

An Authentic Cadence (AC) is a V-I progression in which both the V and I chords are in root position.[2]Steven G. Laitz, The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis and Listening (4th Ed (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2016), 172

Contrapuntal Cadence (CC)

A contrapuntal cadence (CC) is a special case of an imperfect authentic cadence (IAC). It is a V-I progression in which the bass motion is not from ^5 to ^1. Typically it will move from ^7 to ^1 (as in a V6(5) – I or vii0 – I progression) or from ^2 to ^1 (as in a V43 – I or vii06(5) – I progression).[3]Laitz, The Complete Musician, 172.

Deceptive cadence

More often this is called a deceptive cadential progression. It occurs when an authentic cadential progression does not end with a tonic but with a related harmony. Most often this is a chord with the sixth scale degree in the bass (typically vi or VI). [4]William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998), 19.

The deceptive cadence is a special case of an evaded cadence.

Essential Expositional Closure (EEC)

In the Sonata Theory of Hepokoski and Darcy the function of the exposition is to drive to and produce a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in the new key (the dominant in major-mode sonatas and the mediant or minor v in minor-mode sonatas). The first satisfactory PAC within the secondary theme that goes on to contrasting or differing material is called the Essential Expositional Closure. After this point only a Closing Section can follow.[5]Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 18.

Essential Structural Closure (ESC)

According to Hepokoski and Darcy’s Sonata Theory, the Essential Structural Closure (ESC) is the first satisfactory PAC within the secondary theme [within the recapitulation] that goes on to differing material.[6]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, xxvi. According to them this ESC is “the goal toward which the entire sonata-trajectory has been aimed” and “The attaining of the ESC is the most significant event within the sonata”.[7]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 232. In their view the whole of the sonata form is one large structure to secure and stabilise the tonic key, and this point is reached at the end of the secondary theme in the recapitulation with the ESC.

Evaded cadence

An evaded cadence occurs when there is a cadential progression up to the dominant but after the dominant there is no resolution to the tonic but something else happens which has a feeling of belonging to the material to come and not as a closure of that which has been.[8]Caplin, Classical Form, 101-106.

Fauxbourdon

The Fauxbourdon originates from the middle of the fifteenth century. Hymns originally contained only two voices, a cantus firmus and a lower voice, the tenor, which was sung a sixth or an octave lower. To this was added a middle voice a fourth lower than the cantus. The fourth was also called wrong or faulty fifth (because it is the same note as the fifth above the cantus). Faulty is faux in French and fifth is bourdon, thus explaining the name Fauxbourdon. In this way a 6/3 or 8/3 chord is created. Over time the term Fauxbourdon got to be used for a succession of 6/3 chords. The nice thing about this is that these chords can be used to create a sequence without having the problem of parallel fifths or octaves.[9] Job IJzerman, Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 2018), 29-33.

Harmonic mixture

An instance of modal mixture in which the root of the chord is altered. So for instance if in the major mode the chord on the sixth scale degree (which would be minor) is changed to a major chord by lowering the 6, but also the 3.

Imperfect Authentic Cadence (IAC)

An Imperfect Authentic Cadence (IAC) is an authentic cadence in which the soprano voice does not end on the first scale degree (^1); so it ends on the third (^3) or fifth (^5) scale degree, being the only other two scale degrees in a tonic triad. Therefore it has a more open character then a perfect authentic cadence (PAC).

Medial caesura

The medial caesura (MC) is the pauze or break in all voices that often occurs between the end of the transition and the beginning of the second tonal area (talking sonata form). In fact it divides the exposition in two parts: the part of the home key (first tonal area) and the part of the secondary key (second tonal area). In major this is often the dominant of the home key, in minor it is often the mediant.

The adjective medial is added because the caesura often occurs half way the exposition; however Hepokoski and Darcy show that (taking into account various options for the cadence preceding the MC) the MC occurs somewhere between 15 and 70% of the exposition.[10]Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 37.

The break need not be in all voices. If one (or two) voices still contain some notes as bridging material this is called a caesura fill (CF).[11]Hepokoski and Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory, 40.

Melodic mixture

An instance of modal mixture in which the quality of the chord is altered but not its root. So for instance if in the major mode the chord on the fourth scale degree (which would be major) is changed to a minor chord by lowering the 6.

Modal mixture

A technique in which harmonies are borrowed from the relative mode. An example is the Picardy third where a piece in a minor mode ends with a major chord. More common are instances in which elements of the minor mode are imported in the major mode. This is also called Moll-Dur (MD): a lowered (minor) note in a major context. Often used is a lowered sixth in a predominant chord (ii0, iv or VI). When for instance the sixth in a predominant IV is altered it will be notated as: ivMD.

Moll-Dur

See: Modal Mixture

Perfect Authentic Cadence (PAC)

A Perfect Authentic Cadence (PAC) is an authentic cadence in which the soprano voice ends on the first scale degree, typically: ^7-^8 or ^2-^1. Therefore it has a closed character, more so then for instance an Imperfect Authentic Cadence (IAC).

Period

The concept of period is explained in a seperate post: A not so brief introduction to the concept of period

Sentence

The concept of sentence is explained in a seperate post: A brief introduction to the concept of sentence

Tonicization

Tonicization is the experience of another key then the tonic for a certain brief amount of time (ranging from a few beats up to a few bars). A tonicization typically consists of an applied dominant and optionally before that a predominant of the foreign key, and then a statement of the foreign key itself.[12]Laitz, The Complete Musician, 467-468.

Notation syntax

Cadences

A full cadential progression consists of the following harmonies:

Tonic – PreDominant – Dominant – Tonic (T – PD – D – T)

This is also called the phrase model.[13]Laitz, The Complete Musician, 273-277.

In the PD phase the following diatonic chords are possible:

vi – IV – ii in major or VI – iv – ii0 in minor

In the Dominant phase the following chords are possible (among others like diminished seventh chords):

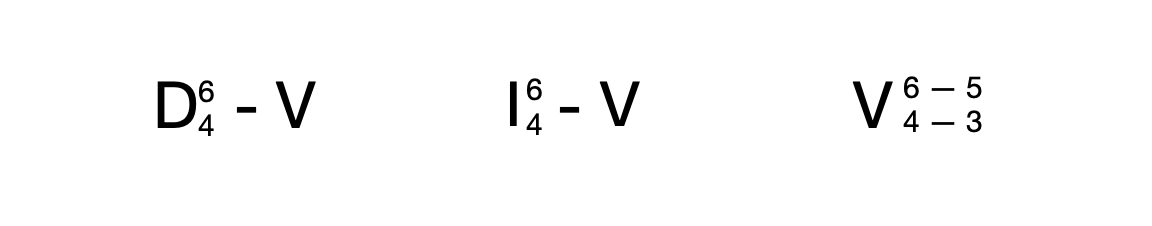

D64 – V

The D64 chord stands for: Dominant six-four chord and is in fact a I64 chord.

The following notations are used for this cadential structure:

The function of the I64 (or D64) chord is in fact a suspension for the dominant chord to come, hence the last notation form in the example.[14]Laitz, The Complete Musician, 308-311.

Notes

| ↩1 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, xxv. |

|---|---|

| ↩2 | Steven G. Laitz, The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis and Listening (4th Ed (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2016), 172 |

| ↩3 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, 172. |

| ↩4 | William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998), 19. |

| ↩5 | Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 18. |

| ↩6 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, xxvi. |

| ↩7 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 232. |

| ↩8 | Caplin, Classical Form, 101-106. |

| ↩9 | Job IJzerman, Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 2018), 29-33. |

| ↩10 | Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 37. |

| ↩11 | Hepokoski and Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory, 40. |

| ↩12 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, 467-468. |

| ↩13 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, 273-277. |

| ↩14 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, 308-311. |

Recent Comments