Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1: an analysis of the development of the fourth movement

Last updated on September 12th, 2025 at 11:03 pm

Table of contents

Introduction

As I was working on the analysis of Schumann’s piano quartet in E-flat major, op.47, I read the book by John Daverio on Schumann.[1]John Daverio, Robert Schumann: Herald of a “New Poetic Age” (New York etc.: Oxford University Press, 1997).

A remarkable feature of the piano quartet is that the exposition has no second theme and that the articulation of the dominant is late in the exposition (find my analysis of the first movement of the piano quartet here). Daverio compares the way in which Schumann and Haydn handle the sonata form and remarks “Similarly, Haydn’s teleological sonata forms […] find a counterpart in the delayed articulation of the dominant that characterizes the exposition of the first and last movements of Schumann’s Opus 41, no 2 [string quartet]”.[2]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 251.

Previously this made me investigate Schumann’s string quartets the posts of which can be found here.

The fact that no second theme can be found in the exposition indicates a continuous or three-part exposition. Terminology regarding the continuous or three-part exposition can be found in the post on the exposition of this movement. Hepokoski and Darcy mention the finale of Haydn’s string quartet in b minor, op.33 no.1 as a typical example of a continuous exposition.[3]Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 52.

This led to a closer examination of this string quartet and so I started a small series on it.

This post is the second in the series and is about the development of the last movement: Finale – presto. The post on the exposition of the last movement can be found here.

As always I want to thank Menno Dekker – my former professor at the conservatory of Amsterdam – for the very useful discussions I have had with him. It keeps improving my understanding of music and more particular music analysis. Our relation has grown into a genuine friendship with the music theory and analysis as a perpetual source of inspiration.

Historical context

Haydn wrote the opus 33 group string quartets in 1781, nine years after the previous group: opus 20. The character is quite different and they are seen as a turning point in western music history and as start of the classical style. Whereas the op.20 quartets lean more towards the learned (baroque) style, the op.33 quartets are more playful and quite accessible. One of the reasons mentioned for this change is that Haydn’s contract with the Esterházy’s had been revised and Haydn was free to distribute his music as he wished. This meant that Haydn aimed for a larger public that was more accustomed to comic opera, street songs and dance music of the time.[4]Floyd Grave and Margaret Grave, The string quartets of Joseph Haydn (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 199 and 201.

Charles Rosen mentions that in the nearly decade that separated the two opus groups Haydn was much engaged with comic opera both in writing and in producing them at the Esterházy court. What he learned in that period he used in writing the quartets op.33.[5]Charles Rosen, The classical style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven (London: Faber and Faber, 1971), 119.

The op.33 quartets have various nicknames among which the Gli Scherzi is probably the most well known. It comes from the fact that the dance movements have been named Scherzo (previously Minuet). Scherzo means also joke in Italian and the fun factor is quite present in the op.33 quartets.

Practical information

In this text a lot of references are made to the score of the fourth movement. This is done by means of the measure number. Ideally you have a score with measure numbers at your disposal. A score can easily be downloaded from IMSLP.

In general notes on analysis you can find some remarks on abbreviations, notation and concepts. Some books that I have been consulting can be found in consulted literature. At least all references made to literature in the notes should relate to entries in the consulted literature. The music examples are made in Musescore 4.

Look here for my use of Sonata Form terminology.

Notational convention for major and minor keys

As for a notational convention of major and minor keys: I will use capitals for major keys and lower-case letters for minor keys. For major keys I will often add the word major and for minor keys the word minor, but in music examples and diagrams the words major and minor will in general be omitted. So B major or B for B major and b minor or just b for b minor.

Most suitable devices

Finally it must be mentioned that although automatic adjustments are made to view these posts on tablets as well as mobile phones, they can best be accessed on a computer/laptop. The reason being that there are various tables and lists (like abbreviations) of which the columns will appear one beneath the other (especially on a mobile phone). If that is the case the coherence will be lost.

Haydn: the string quartet in b minor, op.33 no.1

Fourth movement: Finale – Presto

Global structure

The Finale is in sonata form and contains the following elements:

Measure

1-63fb

63sb-109fb

109sb-194fb

Section

Exposition

Development

Recapitulation

Key (relative to b minor)

i – III

III – V

i

Table 1: layout of the first movement [fb=first beat; sb=second beat]

The development

A downloadable PDF of with my annotations can be found here. I think one can subdivide the development in the following sections:

Measure

63sb-72

73-89fb

89sb-101

102sb-109fb

Section

pre-core

core, part 1

core, part 2

exit

Key (relative to b minor)

III – iv

iv – III:HC

III

VA (active dominant)

Table 2: layout of the Exposition [fb=first beat; sb=second beat]

Overview of the development

For the analysis of the development I again use the Sequence-blocks: the Ratz-Caplin model.[6]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 228-229. This recognizes three main parts in the development: the pre-core, the core and the exit or standing on the dominant. The pre-core is an introduction to the place where the main action takes place: the core. As already shown in table 2, this core consists of two parts. What follows is a section that leads to the active dominant VA (not a key but a chord that implies a resolution, to the tonic b minor, at the start of the recapitulation).[7]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, xxv. It is called exit.

The layout of the Development

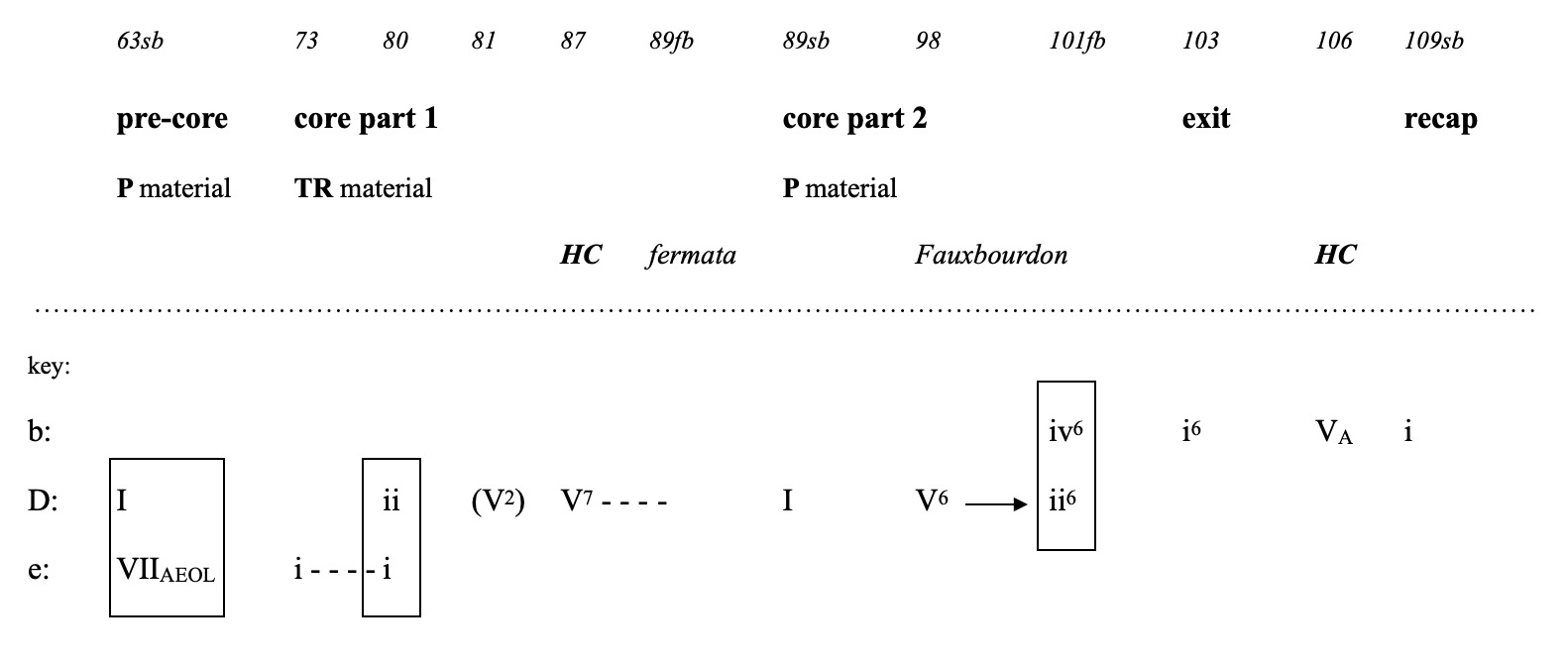

Figure 1 shows the layout of the various aspects of the development. The first line gives the measure number, the second the section of the development. Line three shows from which part of the exposition the material is used and the fourth line gives a few important moments or aspects. Below the line is the harmonic progression divided over three keys. Broadly speaking, the development consists of two tonal areas: D major and b minor.

The e minor area from the start of the development up to m.80 should be interpreted as the predominant ii of D major. I chose to model it as a key because the area is pretty long (almost 18 bars). An alternative would be to model it as a tonicization of e minor within the key of D major.

fig.1 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, layout of the development (fb=first beat, sb=second beat)

Consequently, the D major area would run from m.63sb to m.101fb. The first part (pre-core and core part 1) up to m.89fb can be seen as an expanded cadential progression up to the half cadence (HC) and dominant lock in D major:

predominant ii (mm.63sb-80) – dominant (mm.80-87: HC) – dominant lock (mm.87-89fb)

The core part 2 remains in D major and sequences down from the dominant (m.98) to the supertonic (m.101fb). That e minor chord can also be interpreted as the iv of b minor and than – after a two beat rest – the dominant group starts.

I will now continue with the analysis of the individual sections of the development.

The pre-core

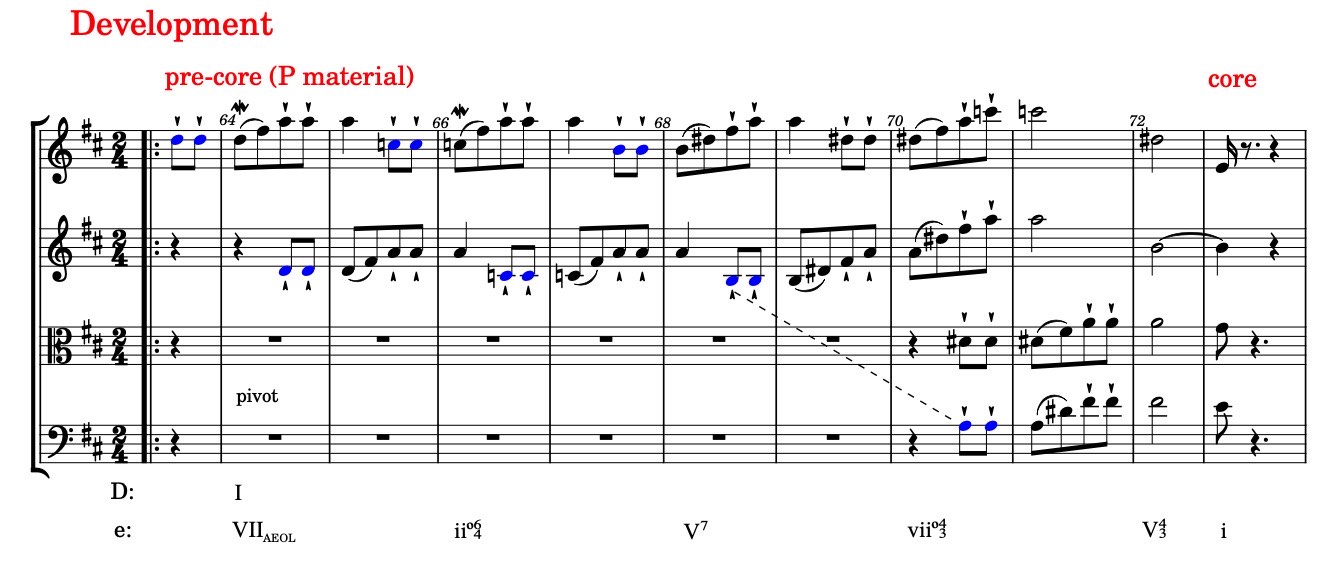

Figure 2 shows the pre-core of the development. Measure 73 is added to show the connection with the next section. Perhaps the first thing that comes to mind is the imitative texture in the first and second violin. The material comes of course from the primary theme (P; exposition fig.1).

fig.2 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, development, pre-core

The first violin plays the u1 motive (exposition fig.2) in a descending second sequence and the second violin imitates this with an overlap. There are three occurrences and then the first violin leaps a third up to a D-sharp (m.69 second beat). The mood is B dominant seventh. There is no imitation in the second violin anymore but after two bars the cello continues the imitation one second lower again (m.70 second beat) and than the end of the pre-core is reached on a second inversion of the dominant of e minor (m.72). So far the contrapuntal aspect seems leading.

Time to look at the harmonic structure. In m.65 the C natural is introduced into the D major chord. The resulting harmony is a D dominant seventh chord but should be seen as the result of the contrapunt (the sequence). A diatonic descend would have been to a C-sharp, so what is Haydn up to? That can be seen in m.66 where the D natural has disappeared and the remaining notes form a f-sharp diminished chord. After this follows a strong B dominant seventh oriented passage (due to the D-sharp), resulting in the dominant seventh chord in second inversion in m.72. In m.73 starts a new phrase (the core part 1) in e minor.

In retrospect the f-sharp diminished chord in m.66 turns out to be a predominant ii0 in e minor. The bars to follow are dominant and seventh chords of e minor. So mm.66-72 is a cadential progression in e minor. Measure 65 should then be seen as passing chord and consequently m.64 is the pivot chord in the modulation to e minor. The D major as tonic of where we came from can also be interpreted as a VIIAEOL of e minor. It is the major triad on the seventh scale degree of a minor key.

Is there any form of a cadence at the end of the phrase (m.72)? Well, that depends on which schooling you adhere to. If you follow the strict modern definition of half cadence (HC)[8]See for instance: William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998), 29. then it should be a triad in root position. That cannot be found here. The chord in m.72 is a dominant seventh chord in second inversion. Caplin would call that a dominant arrival.[9]Caplin, Classical Form, 79.

Poundie Burstein however, argues for a more nuanced approach. He shows that there are a lot of phrase endings on a dominant that is not in root position but on an inversion of the dominant triad or even on a dominant seventh chord or an inversion thereof.[10]L. Poundie Burstein “The half cadence and related analytic fictions” in What is a cadence?: Theoretical and Analytical Perspectives on Cadences in the Classical Repertoire. eds. Markus Neuwirth and Pieter Bergé (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2015), 96-105. And he proposes to describe an ending as in m.72 like the pre-core cadences on a second-inversion V7.[11]Poundie Burstein, “The half cadence and related analytic fictions”, fn.35 on page 104. I think I will follow this because it better describes what one experiences when hearing this phrase ending.

To conclude: the pre-core is a skilful combination of contrapuntal imitation and modulation from D major to (the dominant of) e minor.

The core

As shown in table 2, the core consists of two parts.

The core part 1

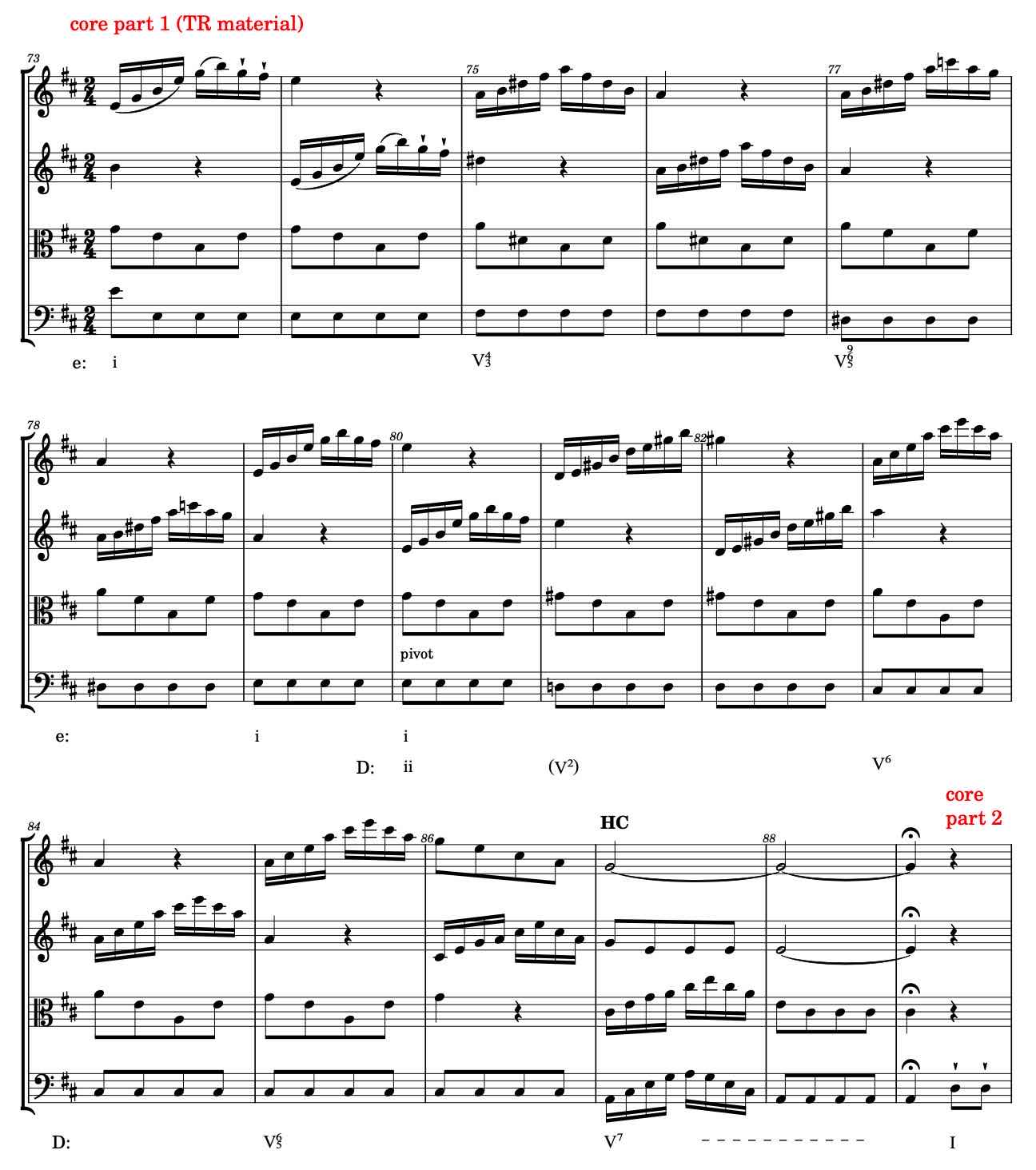

Figure 3 shows the core part 1. A cadential progression in D major (III of b minor), starting with the emphatically positioned e minor predominant. Again an imitation in the violins this time one after the other. The material now comes from the TR=>FS section (exposition fig.3).

fig.3 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, development, core part 1

Imitation is sustained until the half cadence (HC) in m.87. There – during the dominant lock (mm.87-89fb) – the viola and cello once repeat the motive in thirds and then the phrase is over.

Harmonically the first eight measures (mm.73-80) are a tonic prolongation of e minor. In m.80, e minor definitely steps into the role of predominant of D major and (independent) life is over. A cadential progression in D major follows resulting in the half cadence (HC) in m.87. After a short standing on the dominant the rest point on the fermata in m.89 is reached.

Can this be the end of the development? That is not very likely. The A major fermata is not the dominant of b minor (the home key of the movement) but creates in this context a strong expectation for D major.

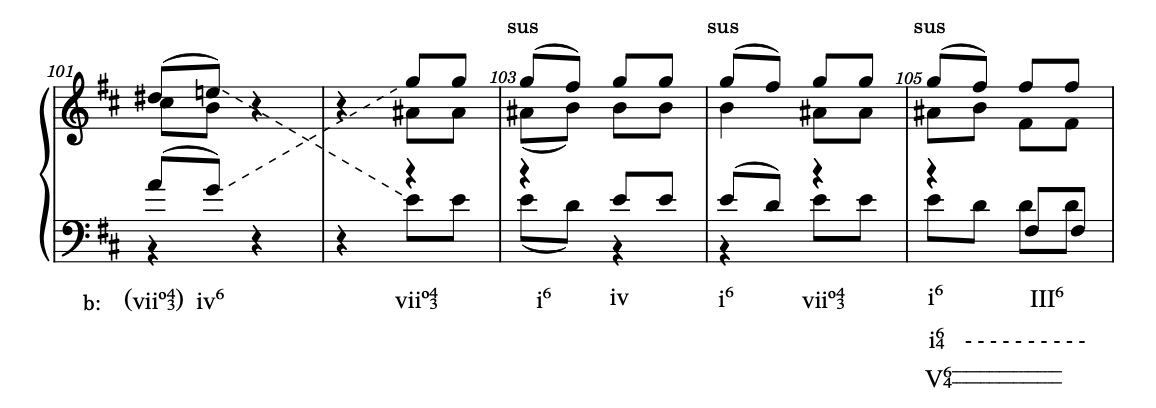

The core part 2

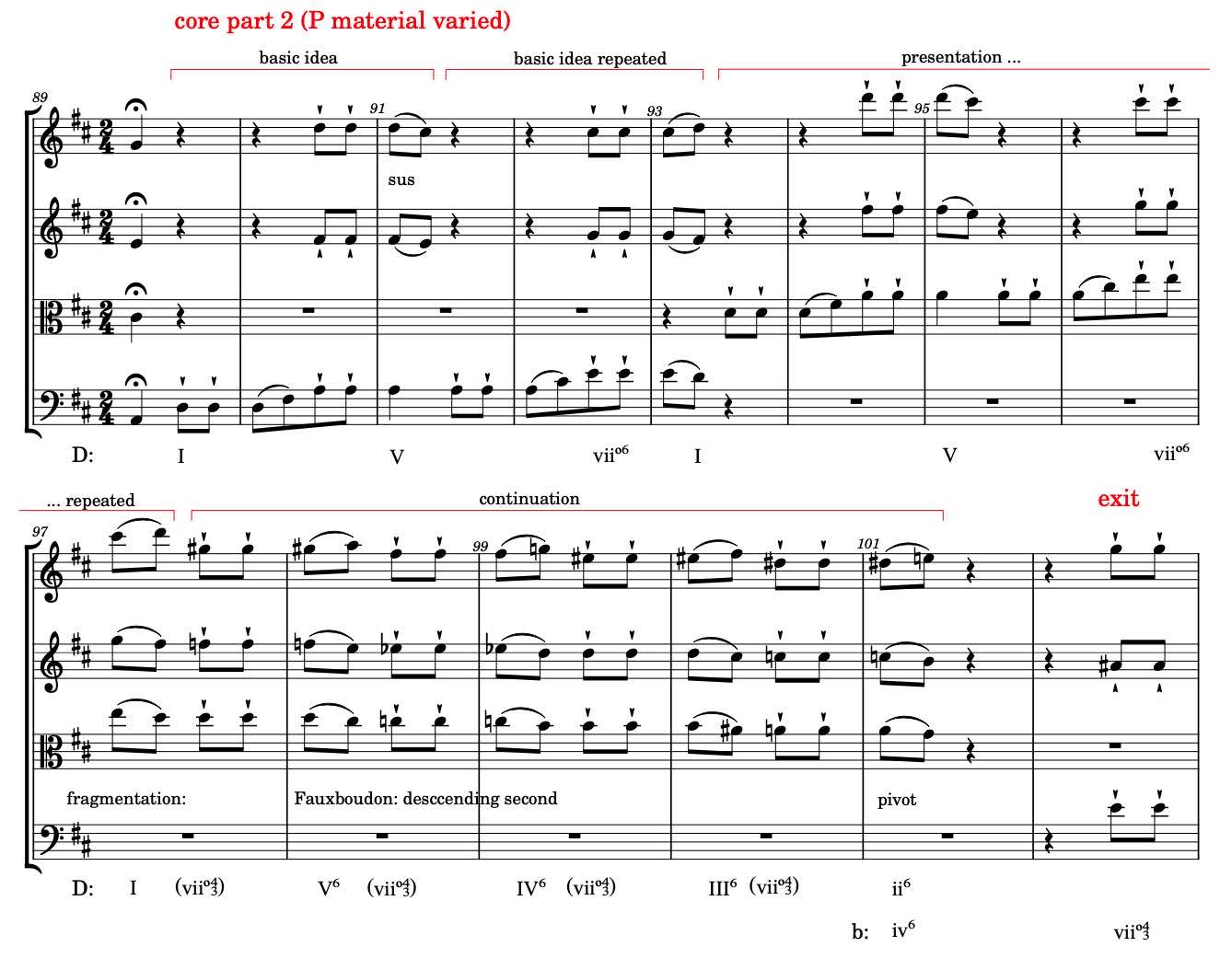

Figure 4 shows the core part 2 that indeed starts in D major. Measure 102 has been included to show the connection with the next section of the development. The cello starts with the u1-motive from the primary theme (exposition, primary theme). The form that Haydn uses here resembles most the form of the first subsection of the TR=>FS section in the exposition. Look here for the annotated score of that whole section and here for the accompanying text in the post on the exposition. The form in question is sentential. An introduction on the sentence concept can be found here.

fig.4 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, development, core part 2

Haydn adds a comment in the violins (mm.90 second beat-91 first beat) to the basic idea. The basic idea is repeated in the dominant and therefore this can be identified as a statement-response presentation.

The presentation is repeated (like the presentation in the first subsection of the TR=>FS section), this time in the viola (mm.93sb-97fb) and then follows a fragmentation of the motive in a descending second Fauxbourdon like sequence, each step preceded by its applied vii043 chord. However, if you see the applied seventh chords as a V without the root then the sequence resembles very much a falling fifth sequence, D2(-5/+4).

The phrase (mm.97sb-101) can be interpreted as a continuation of the sentence like structure. The continuation is only four bars long and the end of the continuation phrase (m.101) is quite Haydnesk: no cadence whatsoever but a ii6 in D major. This predominant creates the expectation for the dominant in D: A major. But the e minor chord is also the iv6 in b minor and indeed functions as the pivot chord in the modulation back to b minor.

Then a two full quarter note rest follows. It is as if you are on a standstill on the highest point of a roller coaster and anxiously looking around what is going to happen next. The two quarter note rests give the listener every opportunity to become aware of her expectations.

The exit

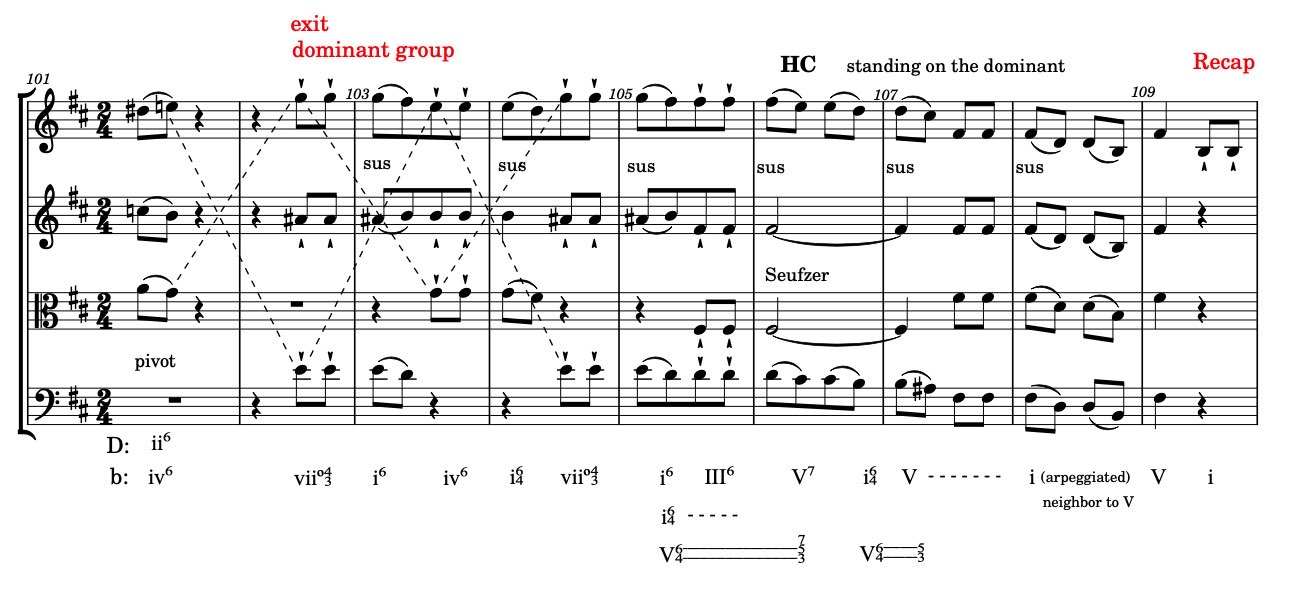

Figure 5 shows the last section of the development: the exit or dominant group which prepares for the recapitulation. Measure 101 is also shown for the connection with the core part 2.

fig.5 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, development, exit

Harmonically this section can be subdivided into two parts:

- mm.102-105: prolongation of i (b minor)

- mm.106-109: prolongation of V (F#)

But perhaps first explain the connection with the previous section. That ended on a ii6 in D major or a iv6 in b minor (m.101). Only when the vii0 and i in b minor are heard the chord in m.101 can be interpreted as the iv in b minor. The progression then becomes a cadential one: iv – vii0 – i.

As of m.102 Haydn applies a voice exchange between the soprano and the bass. This is indicated by the dotted lines in fig.5. If the voice exchange is left out from m.102 onwards the score would have looked like fig.6.

fig.6 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, development, exit without voice exchange

Here one can clearly see the prolongation of i(6) with various neighbouring chords: a vii0 or a iv leading to i. The vii0 to i is cadential, the iv to i is plagal.

If we continue the metaphor from the previous paragraph then this prolongation of i is as if the gondola of the roller coaster moves back and forth for a moment before gliding down to the end of the development in m.109.

Measure 105 is the transition to the dominant area. The viola starts to play the bass and on bar level the harmony is a i64 which in connection with the harmony in m.106 can be interpreted as a V64 suspension. The resolution on the second eighth note in m.106 (after the suspension) can be seen as the arrival on the dominant of b minor, thus a half cadence (HC). The Seufzer leads to a repetition of the V64 – 53 progression and in fact this is a prolongation of or standing on the dominant. The arpeggiated tonic in m.108 should be interpreted as an ornamentation to V.

In the second half of m.109 the recapitulation starts and surely that ends the development section.

Notes

| ↩1 | John Daverio, Robert Schumann: Herald of a “New Poetic Age” (New York etc.: Oxford University Press, 1997). |

|---|---|

| ↩2 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 251. |

| ↩3 | Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 52. |

| ↩4 | Floyd Grave and Margaret Grave, The string quartets of Joseph Haydn (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 199 and 201. |

| ↩5 | Charles Rosen, The classical style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven (London: Faber and Faber, 1971), 119. |

| ↩6 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 228-229. |

| ↩7 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, xxv. |

| ↩8 | See for instance: William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998), 29. |

| ↩9 | Caplin, Classical Form, 79. |

| ↩10 | L. Poundie Burstein “The half cadence and related analytic fictions” in What is a cadence?: Theoretical and Analytical Perspectives on Cadences in the Classical Repertoire. eds. Markus Neuwirth and Pieter Bergé (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2015), 96-105. |

| ↩11 | Poundie Burstein, “The half cadence and related analytic fictions”, fn.35 on page 104. |

Recent Comments