Beethoven piano trio op.11: an analysis of the exposition

Last updated on August 17th, 2025 at 11:44 pm

Table of contents

Introduction

The oeuvre of Beethoven is commonly subdivided in three periods:

- The early period: 1770-1801- youth in Bonn and first decade in Vienna

- The middle period: 1802-1814

- The late period: 1815-1827

As the trio op.11 is written in the beginning of 1798 (or the end of 1797) it belongs to the early period. Beethoven lived in Vienna at the time and the trio is dedicated to countess Maria Wilhelmine von Thun und Hohenstein who was a patron of Beethoven (as she was of Mozart). She was famous for her music salons and a fine pianist herself.

The trio is scored for clarinet or violin, cello and piano. In the analysis I will use the clarinet version.

The nickname Gassenhauer for this trio originates from the final movement, in which Beethoven composed a series of variations on a popular tune of the time. This tune comes from the opera L’Amor Marinaro written by Joseph Weigl (1766-1846), and the song itself is titled “Pria ch’io l’impegno” (which means: “Before I go to work”).

In the Viennese dialect, a “Gassenhauer” referred to a song that was so popular that it was sung or played everywhere on the streets (in the “Gassen”). It was essentially a “street tune” that people in the city would often hear.

Although Beethoven, especially in his early period, was firmly rooted in the classical style, there are already signs during this period that he introduced style-foreign elements into his music. In his book Bach’s Cycle, Mozart’s Arrow, Karol Berger goes so far as to say that two different ontological worlds can be discovered in some of Beethoven’s music. [1]Karol Berger, Bach’s Cycle, Mozart’s Arrow: An Essay on the Origins of Musical Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), Postlude. His first example concerns the piano sonata in C major, op.2 no.3 which was written as early as 1795, i.e. three years before this trio. In this sonata there are great surprises that disrupt the flow of the music, only to return to that original flow as if nothing has happened. I tried to look at the present trio with this in mind. It is difficult to say if we can speak of two different worlds in this movement but there are certainly surprises and disruptions. I will point them out on the way through this movement.

This post is about the exposition of the first movement. The post on the analysis of the development can be found here.

As always I want to thank Menno Dekker – my former professor at the conservatory of Amsterdam – for the very useful discussions I have had with him. It keeps improving my understanding of music and more particular music analysis. Our relation has grown into a genuine friendship with the music theory and analysis as a perpetual source of inspiration.

Practical information

In this text a lot of references are made to the score of the piano trio. This is done by means of the measure number (always within the first movement). Ideally you have a score with measure numbers at your disposal. A score can easily be downloaded from IMSLP.

In general notes on analysis you can find some remarks on abbreviations, notation and concepts. Some books that I have been consulting can be found in consulted literature. At least all references made to literature in the notes should relate to entries in the consulted literature. The music examples are made in Musescore 4.

Sonata form terminology

The first movement is written in the sonata form. Entire books have been written about the sonata form that contain a wealth of information on this concept. Here I am only concerned with the terminology being used. Any self-respecting author creates her/his own names for the various components of the sonata form. Usually there is an agreement on the names of the high level parts:

exposition – development – recapitulation

The terminology on the next (lower) level is more diverse. The sonata form is characterised by the statement of an opening theme in the main or home key. What follows (usually after a component called the Transition) is a contrasting section that differs always in the key being used and possibly also in the melodic/motivic material. These two components of the exposition boast quite a variety of naming. Table 1 provides some of the designations that can be found in the recent literature.

opening theme

contrasting section

Laitz[2]Steven G. Laitz, The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis and Listening (4th Ed, New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2016), Chapter 27: Sonata form.

First tonal area (FTA)

Second tonal area (STA)

Caplin[3]William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998), Chapter 13: Sonata form.

Main Theme

Subordinate Theme

Hepokoski & Darcy[4]James A. Hepokoski and Warren Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), Chapter 2: Sonata form as a whole.

Primary theme/idea (P)

Secondary theme zone (S)

Table 1: some naming of the two theme or key areas in the sonata form

In what follows I will use the terminology proposed by Hepokoski & Darcy as opposed to what I used in the post Comparing the Schumann string quartets. The main reason for the change being the theory of Hepokoski & Darcy on the type 2 sonata form.[5]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, Chapter 17. That theory shows the need to distinguish between different combinations of keys and themes.

For the two other components of the exposition, the Transition (TR) and the Closing Section or Zone (CS), authors generally use more or less the same designation.

Notational convention for major and minor keys

As for a notational convention of major and minor keys: I will use capitals for major keys and lower-case letters for minor keys. For major keys I will often add the word major and for minor keys the word minor, but in music examples and diagrams the words major and minor will in general be omitted. So B major or B for B major and b minor or just b for b minor.

Most suitable devices

Finally it must be mentioned that although automatic adjustments are made to view these posts on tablets as well as mobile phones, they can best be accessed on a computer/laptop. The reason being that there are various tables and lists (like abbreviations) of which the columns will appear one beneath the other (especially on a mobile phone). If that is the case the coherence will be lost.

Beethoven: the piano trio in B-flat major, op.11

First movement: Allegro con brio

Global structure

The Allegro con brio is in sonata form and contains the following elements:

Measure

1-105

106-156

157-254

Section

Exposition

Development

Recapitulation

Key (relative to B-flat major)

I – V

IIIMD – V

I

Table 2: layout of the first movement

The Exposition

The exposition contains the following elements:

Measure

1-19fb

19sb-38fb

38sb

39-46

47-96fb

95-96

96sb-105

Section

Primary theme (P)

Transition (TR)

Medial Caesura (MC)

bridge or S0 module

Secondary theme zone (S)

Essential Expositional Closure (EEC)

Closing section (C)

Key (relative to B-flat major)

I

I – V

vi – V/V

V

V:PAC

V

Table 3: layout of the Exposition [fb=first beat; sb=second beat]

As can be seen in table 3, the secondary theme is pretty long. Quite a few perfect authentic cadences (PAC’s) can be found before the EEC is reached in mm.95-96. Perhaps other choices are possible. This will be discussed in the paragraph on the secondary theme (S).

The Primary theme (P)

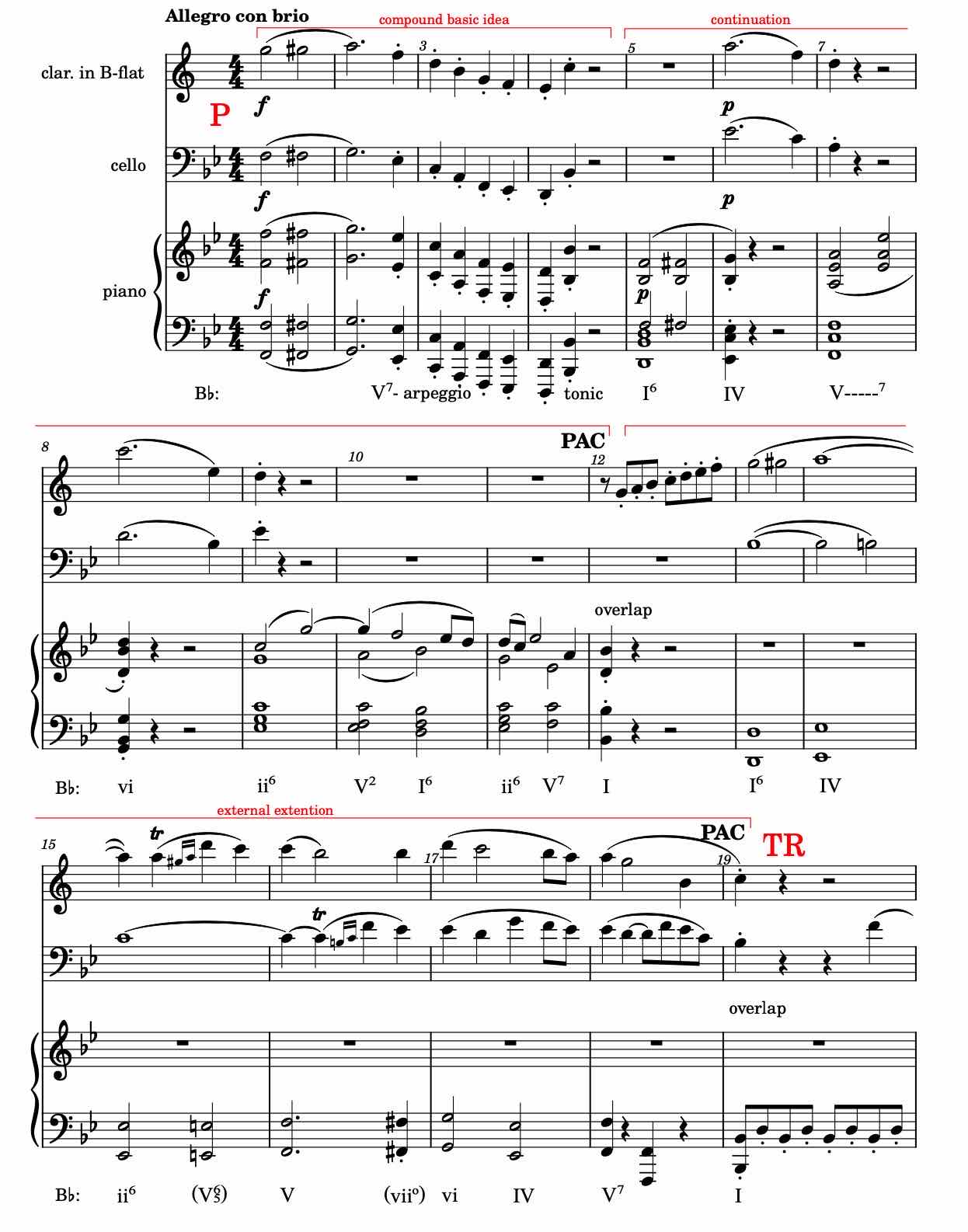

Figure 1 shows the primary theme. Notice that the first stave is the clarinet part (in B-flat, without accidentals) and needs to be transposed. Read it one whole tone lower.

fig.1 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, Primary theme

When looking at the start of the movement we first encounter a four bar phrase (mm.1-4) that is a strong (forte) statement in unison. Starting on the fifth scale degree of B-flat major (F natural) it rises chromatically to the sixth scale degree and then drops to the tonic by way of a dominant seventh arpeggio.

The unison of the voices makes it difficult to identify the harmonies. The most easy way to get an idea of what Beethoven had in mind is to look at mm.5-6 where the piano repeats the opening motive but this time with harmonisation. So the F natural is not harmonized with a V as one perhaps might expect but with a I6, and the G natural – after the passing note F-sharp – turns out to be harmonized as a predominant IV after which a ii – V2 – I6 progression follows. The whole opening phrase then reveals itself as a cadential progression, be it that there are no root chords involved so one cannot speak of a proper cadence.

So we are left with an antecedent like phrase (look here for my post on periods of which antecedents are an essential part) with no cadence to close it.

Caplin would call this a compound basic idea (i.e. a basic idea [mm.1-2] followed by a contrasting idea [mm.3-4] but without a cadence). The combination functions as a higher-level basic idea.[6]Caplin, Classical Form, 61.

Then an eight bar phrase follows (mm.5-12) which ends with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC). I would call this a continuation because of the fragments encountered of the antecedent and the cadential progression in mm.9-12. In terms of Caplin the whole phrase (compound basic idea + continuation) is a hybrid 3.[7]Caplin, Classical Form, 61.

Zooming in on the continuation one discovers a 2+2+4 sentential phrase (look here for my post on sentences). In the presentation (mm.5-9fb) the opening basic idea (mm.5-6) is divided between the piano on the one hand and clarinet and cello on the other. Measure 7 is a variant on the basic idea but resembles harmonically m.3. Notice the bass line in the left hand of the piano: scale degrees 3-4-5 and 6, which point to a cadential progression ending deceptively on a vi in m.8.

The continuation is typically what Leonard B. Meyer calls a gap-fill melody: a disjunct interval (the C-G in m.9) and conjunct intervals (mm.10-11fb) that fill the gap.[8]Leonard B. Meyer, Explaining Music: Essays and Explorations (Berkeley [etc.]: University of California Press, 1973), 145. The C-G interval is a repetition of the response [mm.7-8] a third higher. The continuation ends with a Mozartian cadential progression with a ii6 as the predominant (mm.11-12).

Is the PAC in mm.11-12 the end of the primary theme? Not quite. The clarinet takes a run-up and repeats the opening motive of the trio once again and continues with an ornamental “improvisation” (mm.12-16). The cello imitates this in a contrapuntal way (a reminiscence of the learned baroque style) and the piano imitates it also although without the ornamentation. In its roll as bass it ascends again stepwise but this time chromatically. In m.16 the piano plays a variant (a5) of the opening motive which is emphasised with a sforzando. An overview of the motives is shown in fig.3.

Another perfect authentic cadence (PAC) follows (mm.18-19) this time with a IV as subdominant. Since this phrase follows after the PAC it is an external extension.

Figure 2 shows the diagram of the primary theme. A total of 19 bars, i.e. a four bar compound basic idea, an eight bar continuation and an eight bar external extension with one bar overlap (m.12).

fig.2 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, diagram of the primary theme

Comparing this to the primary theme of Beethoven’s piano trio in D major, op.70 no.1, also referred to as the Geistertrio, one notices the corresponding structure of a compound basic idea and a continuation that has a nested sentence. The difference being of course that in the Geistertrio the presentation of the sentence is repeated within the continuation whereas in the trio op.11 there is an external extension.

The motives of the primary theme (P)

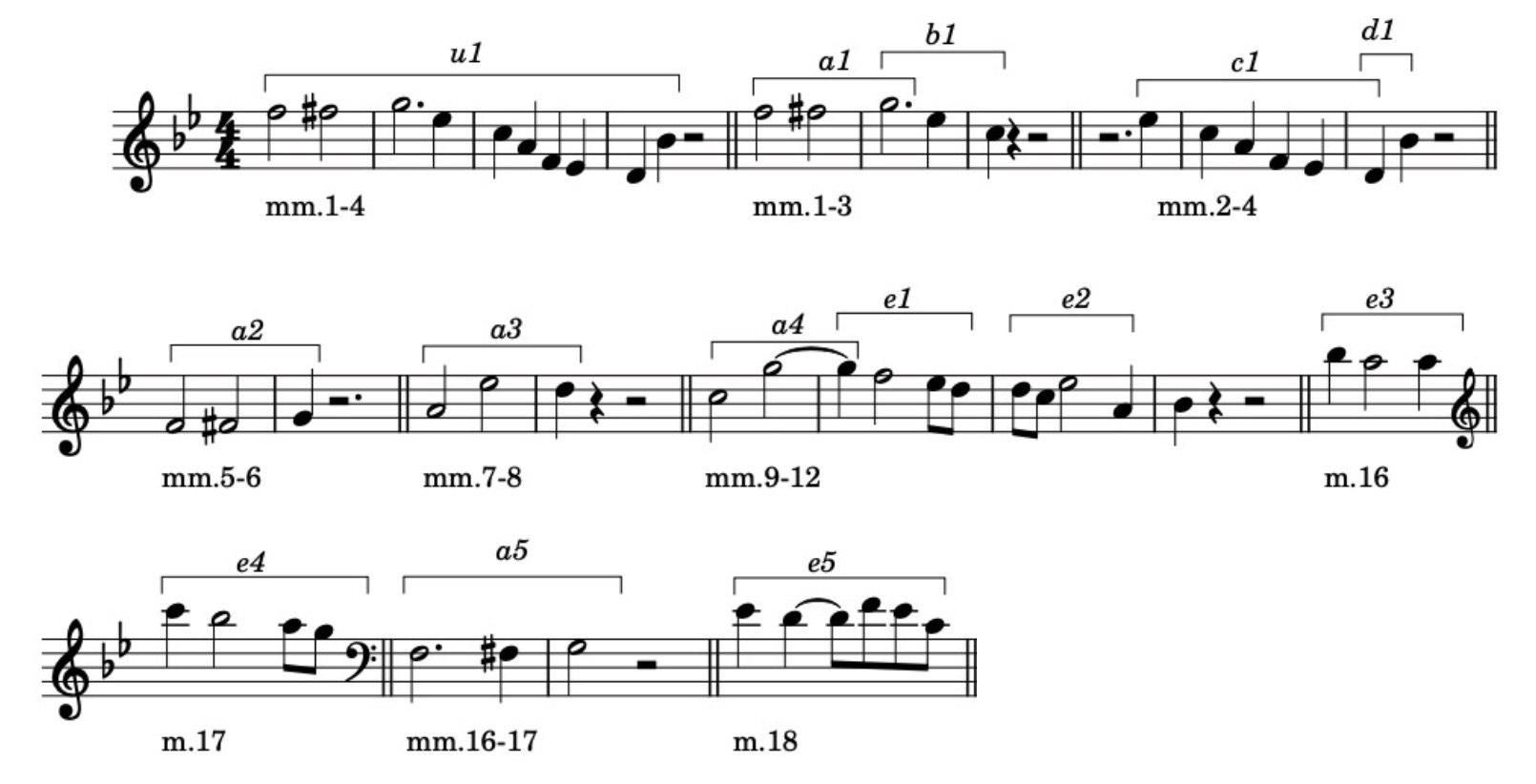

Figure 3 shows the motives of the primary theme.

fig.3 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, motives of the Primary theme

The opening motive u1 is a compound motive in which the motives a1, b1 and c1 may be distinguished. As mentioned before the beginning of the continuation of the nested sentence (m.9) is the a3 motive one third higher. The e-motive family is a very important one as the members are the seed of an important motive in the secondary theme. It is all about the syncopation on the second beat. As you can see it starts with a tied suspension on the first beat of m.10 which becomes more independent in m.16 as it is prepared but not tied. In m.17 the first beat is an appoggiatura, so completely independent but also followed by the syncopation on the second beat.

The Transition (TR)

A downloadable PDF of the transition can be found here. As is to expected the transition is the bridge between the primary and secondary theme. The key of the secondary theme is F major, the dominant of B-flat major, the key in which the first theme was cast. This is also completely according to expectations for a classical style piece in a major key as this trio is.

The question is how Beethoven will take us from the first to the second theme: will the transition modulate to the dominant of the new key (i.e. modulate to C major in the form of a half cadence [V:HC])? Or will it take us to a I:HC (F major as dominant of B-flat major)? According to Hepokoski & Darcy these are the first and second level defaults in this situation, that is, a transition followed by a medial caesura.[9]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 25-27. And then we can ask whether Beethoven uses thematic material from the primary theme or introduces new material. Let’s see how this transition accomplishes its function.

In the transition the following phrases can be distinguished:

Measure

19fb-27fb

27fb-33fb

33sb-38fb

Description

2+2+4 sentence

sentence repeated with truncated cont.

standing on the dominant

Key (relative to B-flat major)

I – V7

I – V

V

Table 4: layout of the Transition [fb=first beat; sb=second beat]

The Transition: first phrase

Figure 4 shows the first phrase, a sentence with the default lengths 2+2+4.

fig.4 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, Transition, first phrase

In m.19 the accompaniment of the transition motive starts immediately. The first beat is in fact an overlap which occurs also in m.21, 23 and 27. The motive in the cello (mm.19 fourth beat – 21 first beat) is the basic idea of the sentence and is repeated in the clarinet. As the chords are the tonic B-flat major respectively its dominant in second inversion it is a statement-response presentation. In the continuation the cello and clarinet play the motive in unison and then a cadential progression follows in which the harmonic rhythm increases, to close with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in B-flat major. A textbook example of a sentence. Notice that harmonically the phrase is completely closed so no signs of modulation whatsoever.

The Transition: second phrase

Figure 5 shows the first phrase, a sentence with a truncated continuation.

fig.5 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, Transition, second phrase

The second phrase starts with the presentation of the sentence of the first phrase, the motive this time played by the piano. The accompaniment is played by the cello and clarinet, be it that the sixteenth runs in the right hand of the piano (m.21 and m.23) are replaced by an eighth note substitute.

In m.31 something like a continuation starts on the second beat with the second half of the basic idea, a so called fragmentation. Immediately a short cadential progression starts leading to the half cadence in B-flat major (I:HC) on the first beat of m.33. So the continuation of the sentence is stopped short after two bars.

Again there is no modulation to be found despite the fact that the end of the phrase is on F major; this should be interpreted as the dominant of B-flat major and not as the arrival in a new key. This dominant is what Hepokoski & Darcy call an active dominant that implies – for the experienced listener – a resolution to the tonic (B-flat major).[10]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, xxv. This is however not what happens as we shall see in the third phrase of the transition.

The Transition: third phrase

Figure 6 shows the third phrase: standing on the dominant.

fig.6 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, Transition, third phrase

So what does Beethoven do with the expectation that a return to the tonic will follow? He just prolongs the dominant with a two times repeated energy gaining phrase of two bars (mm.33sb-35fb and mm.35sb-37fb respectively), confirmed with two fortissimo F major chords. With this standing on the dominant the expectation of a solution to the tonic is only strengthened. It also means that this Transition as a whole must be characterized as non-modulating.

What follows in m.38 is a pauze of three quarters in all voices. This is called a Medial Caesura (MC): a pauze between the Transition and the Secondary theme. Look here for a brief explanation of the MC. It also means that the present Exposition is a two-part exposition (as opposed to a continuous one). The two parts of the exposition being the Primary theme and the Transition on the one hand and the Secondary theme and the Closing section on the other. The MC is the pause that divides these two parts.[11]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 16-18.

The motives of the Transition

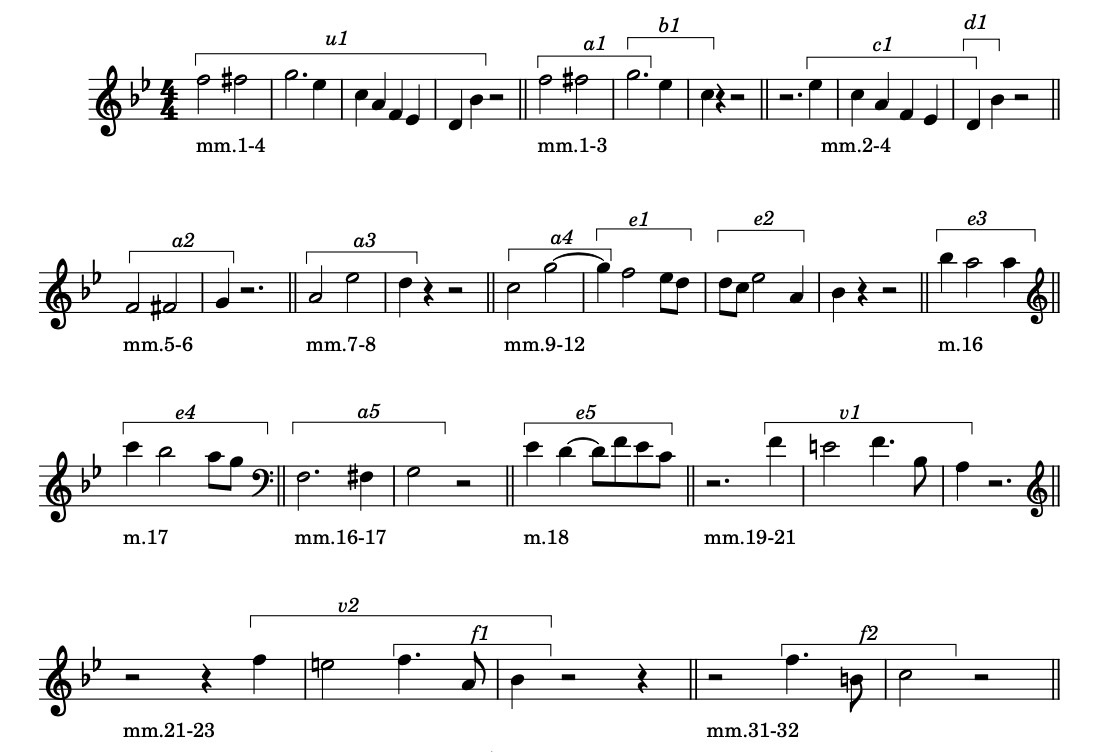

Figure 7 shows the motives up to the Transition.

fig.7 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, motives up to the Transition

The v1 and v2 motives are the (compound) motives of the Transition. The f1 motive is the second half of the v2 motive and returns as fragment f2 in the truncated continuation in m.31. It is clear that the v-motives do not occur in the Primary theme and that means that the Transition should be classified as independent.

The secondary theme zone (S)

A downloadable PDF of the complete secondary theme with my annotations can be found here.

The secondary theme zone is long and consists of several components. The bridge or S0 module is not included in the body of the secondary theme zone which starts with the S1 theme. I would like to propose the following structure for the body of the secondary theme zone:

Measure

47-63fb

63-76fb

76-96fb

95-96

Section

S1 theme

S1 External extension

S2

EEC

Key (relative to F major)

I

I

I

I:PAC

Table 5: layout of the body of the secondary theme zone [fb=first beat; sb=second beat]

An important point to decide was where the secondary theme zone ends and where the Closing section starts. This point is marked by the Essential Expositional Closure (EEC). I considered mm.75-76fb because it is a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) and it is the end of the S1 theme. But then mm.76-96fb (what is called S2 in table 5) would become part of the Closing section. I think there is too much harmonic motion and in fact also motivic development to justify this.

The secondary theme zone: S0

Figure 8 shows the first phrase after the medial caesura (MC).

fig.8 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, Secondary theme, S0

Remember that the Transition ended with a strong half cadence in the tonic (I:HC) and that the secondary theme is in the key of the dominant (F major, m.47). Now look at the first chord in m.39, the first bar after the MC: a D major chord! [Speaking of surprises!] The fact that it is played in pianissimo adds of course to the surprise: a mysterious completely unexpected chord, a different world is entered.

In m.47 the genuine secondary theme (S1) starts in F major as expected. But apparently Beethoven had to sort out something else before he could start that theme. He inserted an eight bar phrase (mm.39-46) which after close inspection is in fact a cadential progression towards F major (the key of the secondary theme). The C dominant seventh chord is reached in m.46 in first inversion and is a good introduction to the secondary theme in F major.

How did he proceed? A cadential progression consists in general of the sequence (tonic -) predominant – dominant – tonic. Backtracking from m.47 (the tonic) we first find the dominant in m.46 and then the predominant ii (g minor) in m.45. The last beat of m.44 is the applied dominant of ii: D major. Ah! … D major, that was the surprise in m.39.

Now we only have to find out what happens from m.39 to m.44 last beat. As follows: g minor is already reached in m.43, so mm.43-45 are in fact a sustained predominant ii. And as it turns out mm.39-42 are the dominant (D major) and the (applied) dominant of the dominant (A major) of g minor. The A major chord is found on the last beat of m.40 and on the second half of m.41. So these four bars (mm.39-42) are a preparation for g minor and therefore I made them a tonicization of that key. In m.43 g minor steps into its role as the predominant of F major.

So to conclude, Beethoven composed a non-modulating Transition which ends with a I:HC, and as if he thought that was unsatisfactory he inserted a cadential progression which ultimately leads to F major in m.47.[12]This line of reasoning is found in: Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 145. This phrase is therefore called S0, “a preparatory phrase that sets up or otherwise precedes what strikes one as the ‘real’ initial theme of the [secondary theme] zone”.[13]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 142.

Perhaps one remark about the motives in this S0 module. In m.42 the cello comes in to finish the first phrase of four bars. It it is in fact a variant of the e4 motive (fig.7). The S0 module will recur at the start of the development and will be revisited there.

The secondary theme zone: S1

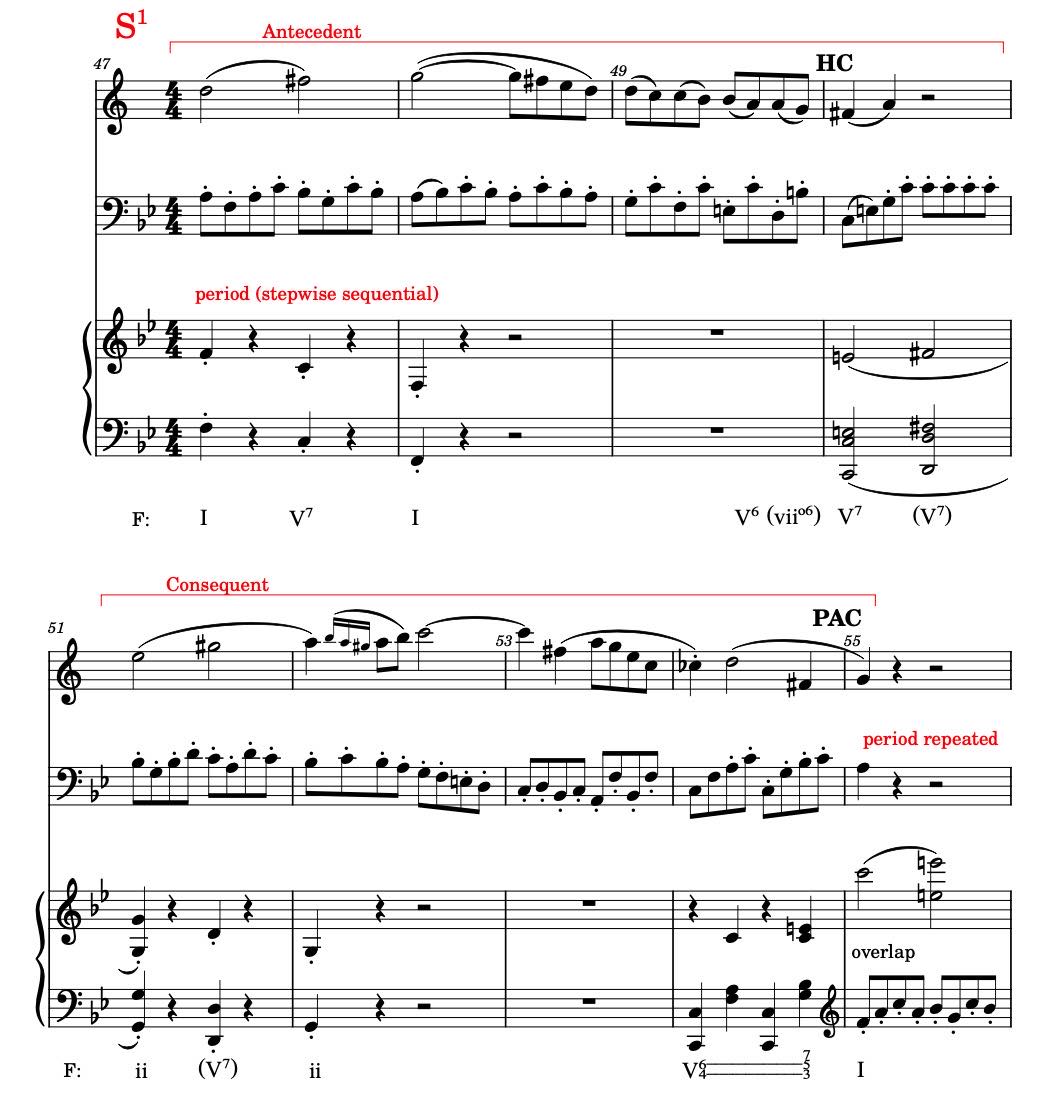

Figure 9 shows the “real start” of the secondary theme S1, the first of a repeated period.

fig.9 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, Secondary theme, S1, first of a repeated period

The secondary theme is opened by the clarinet and has the form of a period. The antecedent is four bars long and ends with a half cadence in the tonic (I:HC, m.50). The consequent has an extension (second half of m.52 – first half of m.53) and is therefore 5 bars long. It ends with a I:PAC in mm.54-55.

The beginning of the consequent is in g minor, the supertonic ii of F major. Beethoven makes the modulation by raising the dominant chord in the piano one whole tone, from C major to D major (m.50). Notice that the C natural is the common tone, changing from the root to the seventh of the chord. The D major functions as the applied dominant of ii as we have seen before (the S0 module, fig.8).

As for whether the PAC in mm.54-55 could be the Essential Expositional Closure (EEC), the short answer is no. Indeed, the period is immediately repeated (mm.55-63) with the theme in the piano and also ends with a I:PAC. This can be found in the PDF-score in mm.62-63 and also in fig.11. The repetition of the period negates the EEC effect of the first PAC.

As m.55 is an overlap the combined periods make a total of two times 9 measures minus one overlap, totalling 17 bars.

The PAC in mm.62-63 is a more serious candidate for the EEC but it is questionable whether it can live up to this function after scrutiny. Before starting the inquiry we have to look at the motives of the secondary theme S1.

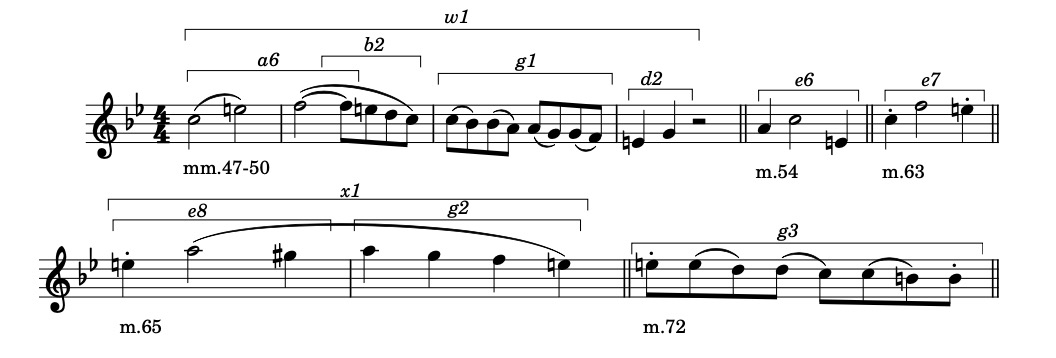

The motives up to S1 of the secondary theme zone

Figure 10 shows the motives of the first movement up to the S1 theme.

fig.10 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, motives up to the S1 theme

The compound motive w1 is the antecedent of the S1 theme. If we compare a6 with a1 we notice a striking resemblance. It is the same half note rising motive (with a different starting interval, of course). What follows is a falling motive b2 which resembles b1 although here with conjunct intervals. The names a6 and b2 were chosen for good reason. Even the g1 motive can be compared to the c1 motive but here I think the differences are too big so I gave it a new name.

The conclusion however must be that the secondary theme S1 is what Hepokoski and Darcy call a P-based, in this case “an easy recognizable variant of the P [=Primary] theme”.[14]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 135. This also brings into focus the term “monothematic exposition”. To see whether that could be applicable we should launch an investigation into what follows (including the Closing zone if present), as we have already noted. We’ll come to that shortly.

One last thing about the motives in the S1 theme: in the consequent (mm.51-55, fig.9) of the period the same motives occur, be it with ornamentations. I just want to highlight m.54 because it reflects a motive from the e-motive family that, as already mentioned, will play an important role in the things to come. As shown in fig.10 it is called the e6 motive. In the repetition of the period it can be found in m.62 in the right hand of the piano part, here for the first time with the sforzando on the syncopated second beat (see the PDF-score of the S theme or fig.11).

The external extension of S1 (mm.63-76fb)

This is where we begin to explore what follows the PAC (mm.62-63) ending the repeated period of the S1 theme.

As shown in fig.11 the second phrase (mm.63-76fb) ends with another perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in mm.75-76. Measure 62 is shown for the connection with the S1 theme.

fig.11 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, S zone, second phrase

The external extension of S1: the form

The phrase can be divided into three sub phrases or sections:

Measure

63-67fb

67-70

70-76fb

Section no

1

2

3

Description

antecedent like phrase

modulating consequent like phrase

continuation like phrase with a 2+2+3 stucture

Table 6: sections in the external extension of S1 [fb=first beat]

The recurring motive in the left hand of the piano in m.67 may initially give the impression of a parallel period with voice exchange. But in retrospect – after hearing the third section – the whole extension turns out to have a sentence like 4+4+7 structure. So the antecedent like phrase becomes the basic idea of the sentence like structure and is repeated in the second section which is then the repetition of the basic idea.

There are two overlaps in the whole phrase: the first beat of m.67 and the whole of m.70.

Looking more closely at the first section (mm. 63-67fb) one finds a sequential repetition of the e-motive in the clarinet (e7) with an imitation in the right hand of the piano. The sequence is an ascending second one A2(+5/-4) where the fifth jump up (+5) is on the fourth beat of the bar and the fourth down (-4) on the second beat of the next bar. Look here for some explanation on the notation of sequences.

The first section is finished with a stylized version (g2) of the g-motive (m.66) in three voices. Harmonically this is quite a strong cadential progression which ends on the first beat of m.67 (the overlap). This is a tonic chord (F major) but not in root position, the reason being that this is also the start of the e-motive in the left hand of the piano. The bass note is veiled.

The whole sequential phrase is repeated (second section, mm.67-70) with the motive in the left hand of the piano and the imitation in the clarinet and cello. The right hand of the piano plays ornamental thrills. So the conclusion must be that in the first and second section of the extension Beethoven is continuing with two fragments of the S1 theme (the e6-motive and the g-motive).

Harmonically the second section starts the same as the first section (with an A2(+5/-4) or ascending fifth sequence). The end is different however. Measure 70 also starts with the mediant of F major (a minor), but this time the mediant is confirmed by a cadential progression. Therefore I made it a tonicization of a minor.

Measure 70 is also the start of the seven-bar third section of the phrase. The whole bar is an overlap between the second and third section. The third section can be subdivided in three times two bars and the closing bar (m.76). The stylized version (g2) of the g1 motive (fig.12) is repeated in m.71 in the piano and these two bars are the first set of two bars that is repeated twice. Measures 72-73 repeat the g1-motive albeit that is it shifted one eighth note in the bar (g3). The last two bar set (mm.74-76fb) repeats the motive in the clarinet and cello with a contrapuntal setting in the piano and closes on the first beat of m.76.

Harmonically this phrase alternates between a minor and F major. For each of these keys the (cadential) harmonic progression is always the same:

iii/III – ii6 – V64==53 – I/i

In fact it is a harmonic standstill and the repetition builds up a tension because with every new occurrence the listener asks herself when and how is it going to end. The redemption comes in the form of the perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in mm.75-76, which gained power due to the repetitive structure preceding it.

The question remains to be answered why this phrase (mm.63-76fb) is an extension. Looking at the motivic material in the second phrase we only find fragments of the S1 material (fig.12). So nothing new is introduced. Harmonically the phrase starts with the repeated sequence and then continues with the oscillation between a minor and F major. So these are relatively short harmonic elements that lead to the PAC in m.75-76. The whole phrase has the character of a reinforcement of the S1 module.

Are there any other interpretations possible of this whole phrase (S1 plus extension)? Well, I can think of one – admittedly a bit far-fetched – option: interpret the first period of S1 (mm.47-55fb) as the first half of the presentation of a large scale sentential structure and the repetition of the period (mm.55-62) as the repetition of the basic idea, i.e. the second half of the presentation. The next phrase (the extension, mm.63-76fb) can than be seen as the continuation and cadence. This fits nicely with the fragmentation and the increased harmonic rhythm in mm.63-76fb. An argument against this interpretation is probably the fact that the presentation of the sentence contains two perfect authentic cadences. But then again it is not a regular sentence either.

Whichever option is chosen, the PAC in mm.75-76 is the end of the S1 module.

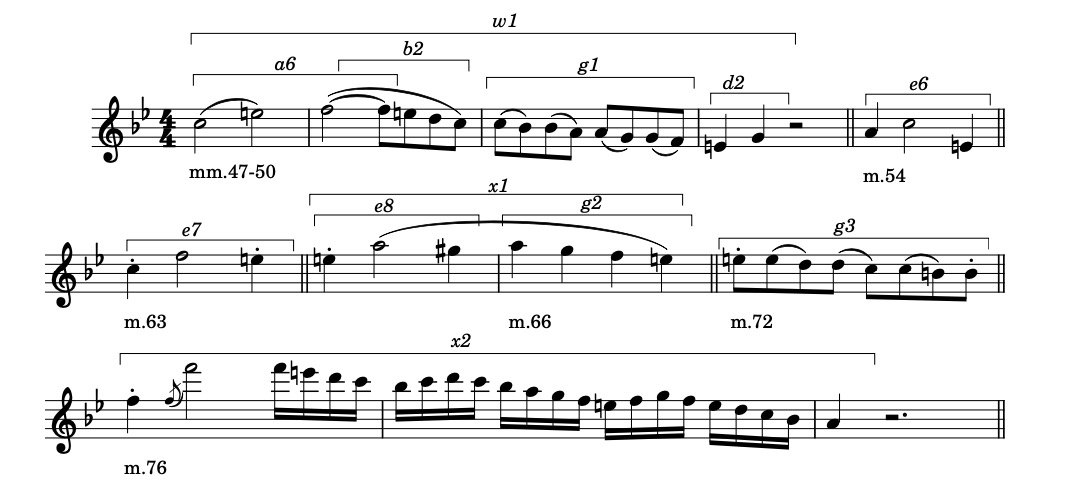

The secondary theme zone: the motives up to the extension of S1

So this concerns the whole of the S1 theme, the extension included (mm.47-76fb). Figure 12 shows the motives as encountered thus far in the secondary theme.

fig.12 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, motives up to the extension of S1

Notice that Beethoven couples two motives from different themes: the e-motive, whose origin is found in the primary theme (P), and the g-motive from the secondary theme zone (S). The composite motif thus created is called x1.

The secondary theme zone: S2

Again we have to wonder whether this is the beginning of the closing section (and the PAC in mm.75-76 is the end of the secondary theme zone [EEC]) or that this is the second module of the secondary theme zone. I chose to model this as the second module of the secondary theme zone (S2) and I hope in the sequel to justify this choice.

The S2 theme can be subdivided as follows:

Measure

76-83

84-88

88-91

92-96fb

Section no

1

2

3

4

Description

S2 motive

sequence and evaded cadence (EC) twice

sequence D2(-5/+4) from ii to V/V (relating to F major)

cadential area

Table 7: sections of S2

The S2 module of the secondary theme zone: first section

Figure 13 shows the first section (mm.76-83).

fig.13 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, S2, section 1

The section starts with a two bar motive in the piano which is almost exactly repeated in the cello in mm.80-81. In between the clarinet plays a variation of this motive. The section is closed with a descending scale in F major which ends on a G natural on the fourth beat of m.83. It creates a strong expectation for an F natural.

Harmonically the section starts with a prolonged (local) tonic: F major (mm.76-80fb). The cello version of the motive is harmonized with the dominant six-four suspension followed by the dominant seventh chord which leads to the tonic on the first beat of m.82. This whole progression is weakened by the pedal on F natural and therefore the listener doesn’t experience much of a rest point or cadential arrival. This is reinforced by the ongoing scale which suggests an arrival on F natural.

The secondary theme zone: the motives up to S2

In fig.14 the motive of S2 has been added. It starts with the characteristic syncopation on the second beat (m.76) and the tail is a variation on the g-motive family. It definitely is an improvisation on the just introduced x1 motive and is therefore called x2.

fig.14 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, motives up to S2

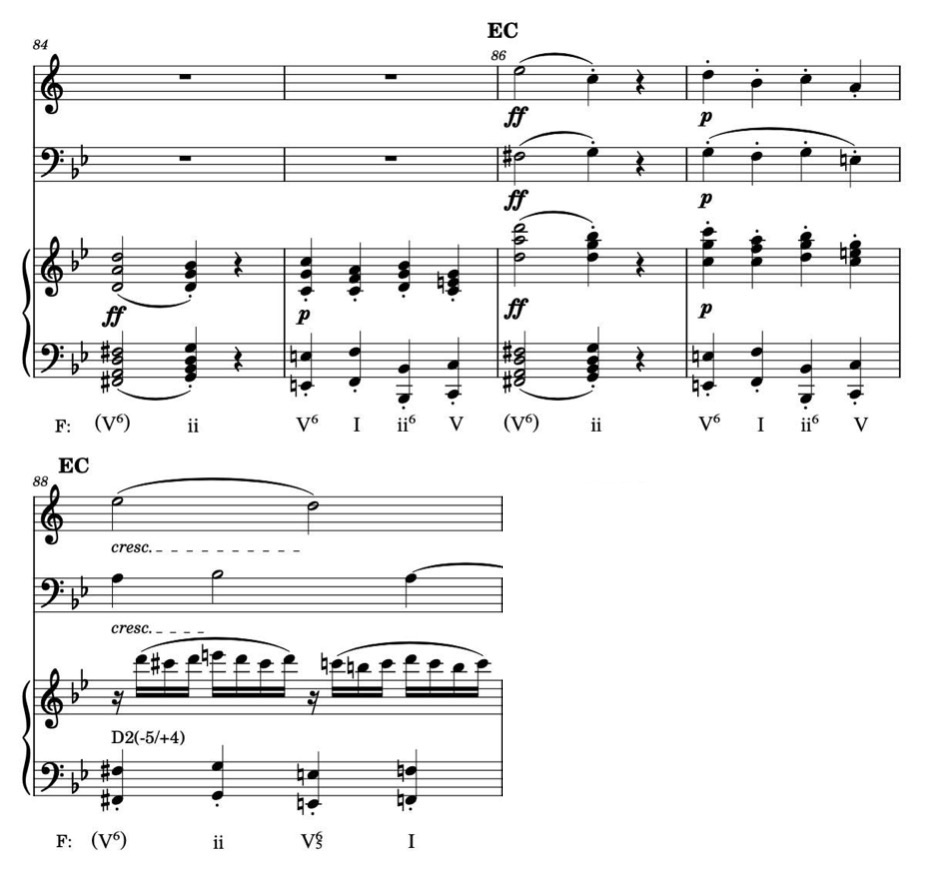

The S2 module of the Secondary theme zone: second section [H5]

Figure 15 shows the second section of S2.

fig.15 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, S2, section 2

As fig.15 clearly shows, the expectation is not met. In stead of an F natural (or an F major chord) there is again the surprise of D major (m.84). It has the same function as the D major chord in m.39 (fig.8): an applied dominant of the ii (g minor) of F major. The ii follows on the third beat of m.84. In m.85 follows a cadential progression (with a ii6 as predominant) from the second beat onwards which is preceded by an incomplete neighbouring chord (V6) on the first beat of that measure. The cadence fails to materialize, to put it mildly. There is no I6 and neither a deceptive vi, but a repetition of the applied dominant of ii, D major. So this is what is usually called an evaded cadence (EC). The two measures (mm.84-85) are repeated in mm.86-87. Again an evaded cadence and this sets off a falling fifth sequence, D2(-5/+4), in m.88.

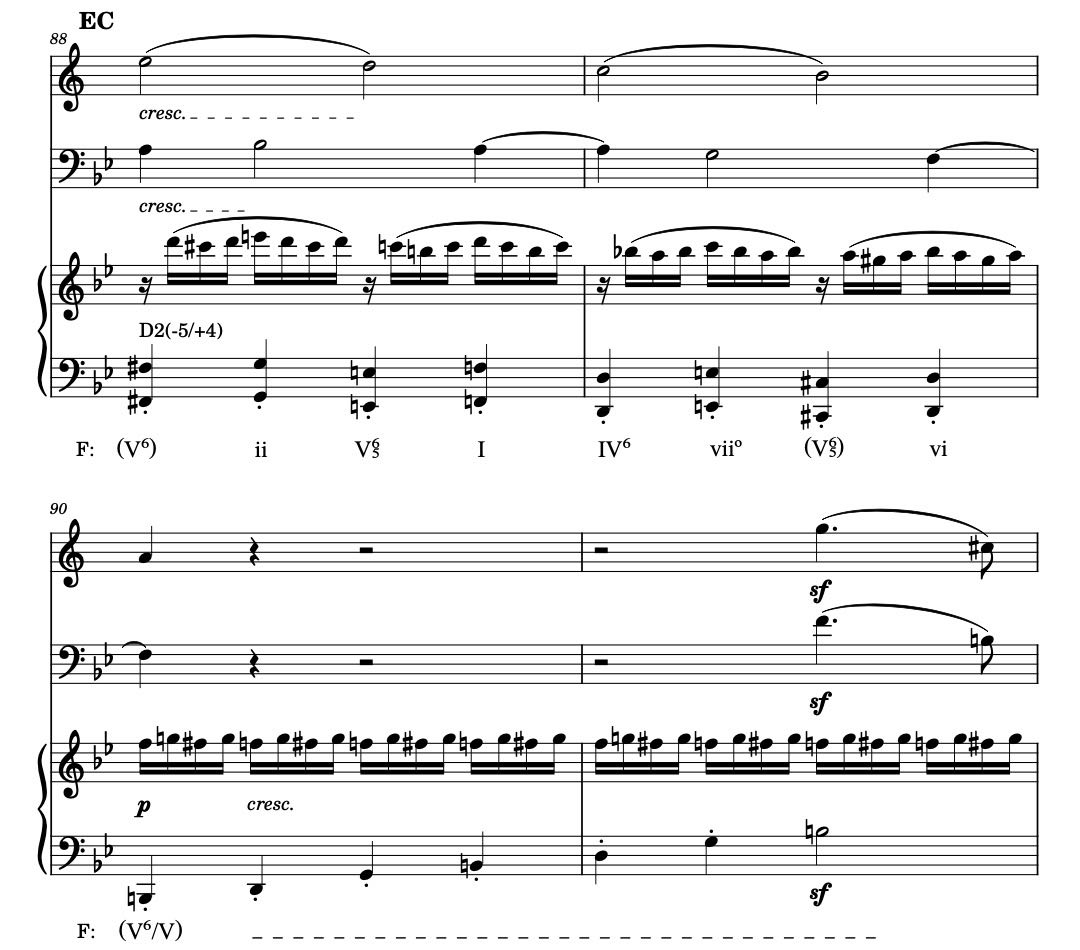

The S2 module of the secondary theme zone: third section [H5]

The falling fifth sequence is shown in fig.16. First I will explain the sequence.

fig.16 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, S2, section 3

The roman numerals are shown beneath each system, all in relation to F major. With the chords added it looks like this:

(V6) [D] – ii [g] – V65 [C] – I [F] – IV6 [B-flat] – vii0 [e0] – (V65) [A] – vi [d] – (V6/V) [G]

And with only the chords and the distance between them (the chords, not the bass notes):

D -5 g +4 C -5 F +4 B-flat -5 e0 +4 A -5 d +4 G

I hope this explains the notation D2(-5/+4): a descending second sequence by moving first a fifth down (-5) and then a fourth up (+4). The sequence of descending seconds (D2) is the following:

g – F – e0 – d

The complete sequence coincides with a falling fifth sequence because a fourth up is the same as a fifth down. The chords have different qualities (major, minor or diminished) because they are all diatonic in the key of F major, with the exception of the applied dominants D major, A major and G major.

So this phrase brings us down from the ii (g minor in m.88 second beat) to the dominant of the dominant (G major, m.90) of F major. As we will see in the sequel the sequence will be pushed one step further to the dominant of F major but only after a dominant six-four suspension.

The S2 module of the secondary theme zone: fourth section

And finally the last section of the S2 module is reached and this is also the last part of the whole of the secondary theme zone which turns out to be fifty measures long, almost half of the exposition. Fig.17 shows this fourth and last section of S2.

fig.17 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, S2, section 4

This section consists of the dominant (mm.94-95), the preceding dominant six-four suspension (mm.92-93) and the resolution to the tonic (m.96fb). The arrival on the dominant in m.94 can be seen as the last step in the descending second sequence that started in m.88 (fig.16).

Notice that the figure in the right hand of the piano in mm.92-93 resembles the figure in mm.90-91. The F natural first plays the role of the seventh in the G major seventh chord (mm.90-91) and then the role changes to the fourth of the dominant six-four suspension chord of F major (92-93).

In retrospect the sections 3 and 4 are in fact an extended cadential progression that keeps putting off the closure of the second theme. It heightens the tension and pushes the expectations to a high point; at last the long expected Essential Expositional Closure (EEC) follows in mm.94-96fb.

The closing section (C)

Figure 18 shows the Closing section.

fig.18 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, Closing section.

Here, the accompaniment figure of the S1 theme in the cello (mm.45-54, fig.9) is combined with the e4 motif from the main theme (m.17, fig.1). So a closing section that harks back to the main theme. The e4 motive is repeated thrice in the piano and clarinet each and this defines the two phrases in this section. The rest points are in m.100fb and mm.104-105. Harmonically it is a repetition of a V7-I construction, so the melody defines the structure. One could say: two codetta’s confirming the key of the second theme, F major.

This concludes the analysis of the exposition of this trio.

Notes

| ↩1 | Karol Berger, Bach’s Cycle, Mozart’s Arrow: An Essay on the Origins of Musical Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), Postlude. |

|---|---|

| ↩2 | Steven G. Laitz, The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis and Listening (4th Ed, New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2016), Chapter 27: Sonata form. |

| ↩3 | William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998), Chapter 13: Sonata form. |

| ↩4 | James A. Hepokoski and Warren Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), Chapter 2: Sonata form as a whole. |

| ↩5 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, Chapter 17. |

| ↩6 | Caplin, Classical Form, 61. |

| ↩7 | Caplin, Classical Form, 61. |

| ↩8 | Leonard B. Meyer, Explaining Music: Essays and Explorations (Berkeley [etc.]: University of California Press, 1973), 145. |

| ↩9 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 25-27. |

| ↩10 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, xxv. |

| ↩11 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 16-18. |

| ↩12 | This line of reasoning is found in: Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 145. |

| ↩13 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 142. |

| ↩14 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 135. |

Recent Comments