Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1: an analysis of the exposition of the fourth movement

Last updated on December 12th, 2025 at 11:51 pm

Table of contents

Introduction

As I was working on the analysis of Schumann’s piano quartet in E-flat major, op.47, I read the book by John Daverio on Schumann.[1]John Daverio, Robert Schumann: Herald of a “New Poetic Age” (New York etc.: Oxford University Press, 1997).

A remarkable feature of the piano quartet is that the exposition has no second theme and that the articulation of the dominant is late in the exposition (find my analysis of the first movement of the piano quartet here). Daverio compares the way in which Schumann and Haydn handle the sonata form and remarks “Similarly, Haydn’s teleological sonata forms […] find a counterpart in the delayed articulation of the dominant that characterizes the exposition of the first and last movements of Schumann’s Opus 41, no 2 [string quartet]”.[2]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 251.

Previously this made me investigate Schumann’s string quartets the posts of which can be found here.

The fact that no second theme can be found in the exposition indicates a continuous or three-part exposition. I will explain some terminology involved in the paragraph called TR=>FS or expansion section below. Hepokoski and Darcy mention the finale of Haydn’s string quartet in b minor, op.33 no.1 as a typical example of a continuous exposition.[3]Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 52.

This led to a closer examination of this string quartet and so I started a small series on it.

This post is the first in the series and is about the exposition of the last movement: Finale – presto. The post on the development of this movement can be found here.

As always I want to thank Menno Dekker – my former professor at the conservatory of Amsterdam – for the very useful discussions I have had with him. It keeps improving my understanding of music and more particular music analysis. Our relation has grown into a genuine friendship with the music theory and analysis as a perpetual source of inspiration.

Historical context

Haydn wrote the opus 33 group string quartets in 1781, nine years after the previous group: opus 20. The character is quite different and they are seen as a turning point in western music history and as start of the classical style. Whereas the op.20 quartets lean more towards the learned (baroque) style, the op.33 quartets are more playful and quite accessible. One of the reasons mentioned for this change is that Haydn’s contract with the Esterházy’s had been revised and Haydn was free to distribute his music as he wished. This meant that Haydn aimed for a larger public that was more accustomed to comic opera, street songs and dance music of the time.[4]Floyd Grave and Margaret Grave, The string quartets of Joseph Haydn (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 199 and 201.

Charles Rosen mentions that in the nearly decade that separated the two opus groups Haydn was much engaged with comic opera both in writing and in producing them at the Esterházy court. What he learned in that period he used in writing the quartets op.33.[5]Charles Rosen, The classical style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven (London: Faber and Faber, 1971), 119.

The op.33 quartets have various nicknames among which the Gli Scherzi is probably the most well known. It comes from the fact that the dance movements have been named Scherzo (previously Minuet). Scherzo means also joke in Italian and the fun factor is quite present in the op.33 quartets.

Practical information

In this text a lot of references are made to the score of the fourth movement. This is done by means of the measure number. Ideally you have a score with measure numbers at your disposal. A score can easily be downloaded from IMSLP.

In general notes on analysis you can find some remarks on abbreviations, notation and concepts. Some books that I have been consulting can be found in consulted literature. At least all references made to literature in the notes should relate to entries in the consulted literature. The music examples are made in Musescore 4.

Look here for my use of Sonata Form terminology.

Notational convention for major and minor keys

As for a notational convention of major and minor keys: I will use capitals for major keys and lower-case letters for minor keys. For major keys I will often add the word major and for minor keys the word minor, but in music examples and diagrams the words major and minor will in general be omitted. So B major or B for B major and b minor or just b for b minor.

Most suitable devices

Finally it must be mentioned that although automatic adjustments are made to view these posts on tablets as well as mobile phones, they can best be accessed on a computer/laptop. The reason being that there are various tables and lists (like abbreviations) of which the columns will appear one beneath the other (especially on a mobile phone). If that is the case the coherence will be lost.

Haydn: the string quartet in b minor, op.33 no.1

Fourth movement: Finale – Presto

Global structure

The Finale is in sonata form and contains the following elements:

Measure

1-63fb

63sb-109fb

109sb-194fb

Section

Exposition

Development

Recapitulation

Key (relative to b minor)

i – III

III – V

i

Table 2: layout of the first movement [fb=first beat; sb=second beat]

The Exposition

The exposition contains the following elements (EEC stands for Essential Expositional Closure):

Measure

1-12fb

12sb-51

50-51

52-109fb

Section

Primary theme (P)

TR=>FS or expansion section

EEC

Closing section (C)

Key (relative to b minor)

i

i – III

III:PAC

III

Table 3: layout of the Exposition [fb=first beat; sb=second beat]

As mentioned in the Introduction there is no secondary theme and that makes this a continuous or three-part exposition. I’ll come to that when discussing the Transition (TR) ==> Fortspinnung (FS) section of the exposition.

The Primary theme (P)

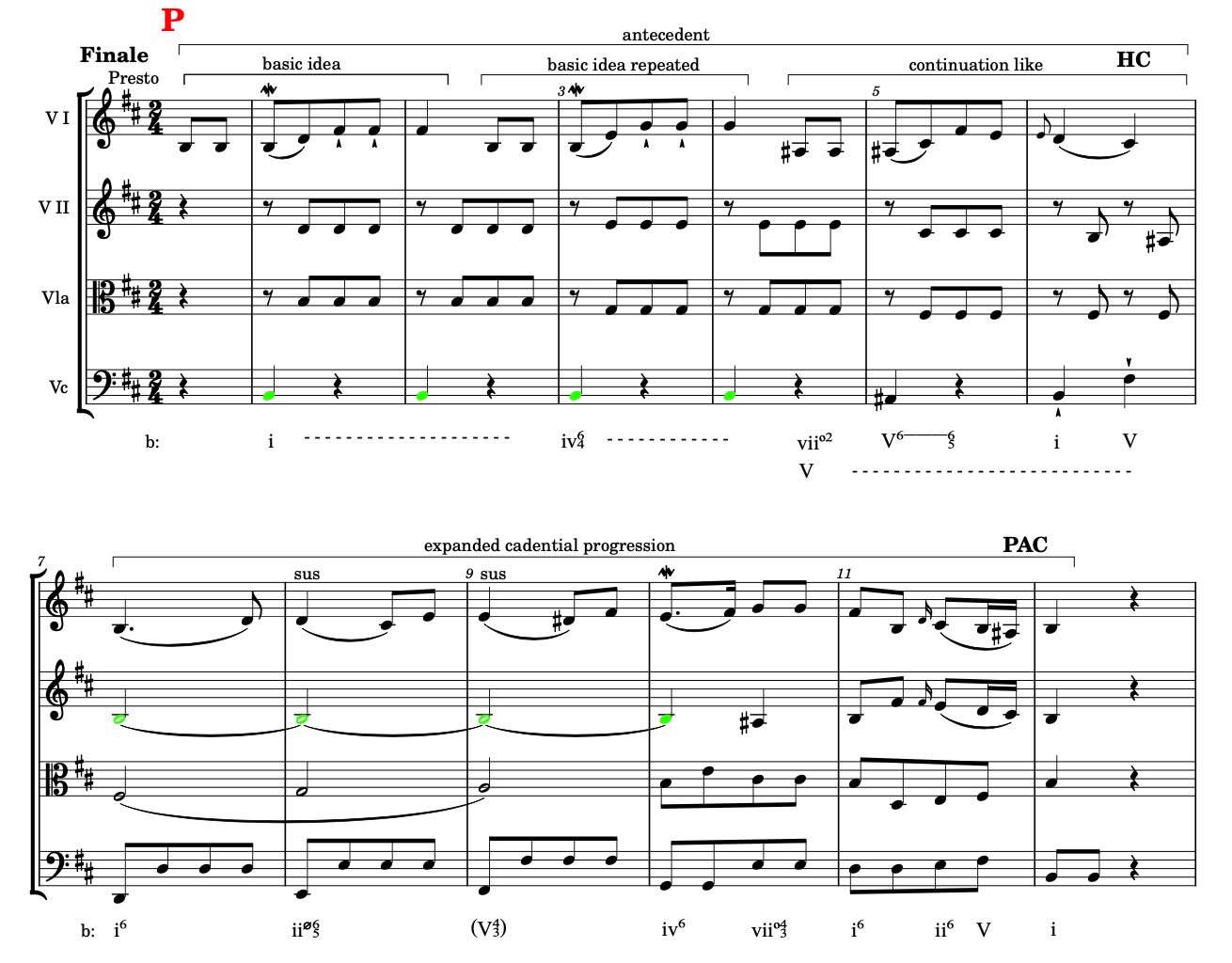

Figure 1 shows the primary theme.

fig.1 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, mm.1-12

I would say this is a hybrid theme of type 2 in terms of Caplin.[6]William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998), 61.

That is to say an antecedent (mm.1-6) followed by an expanded cadential progression (ECP; mm.7-12fb). The antecedent closes with a half cadence (HC) in m.6 and the cadential with the stronger perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in mm.11-12fb. The concept of antecedent is explained in my post on periods. Notice that the division of the whole phrase (12 bars) is asymmetrical: the antecedent is six and a half bars long whereas the expanded cadential progression is five and a half bars.

Looking closer into the antecedent one can make out a sentential structure be it that it is truncated in the continuation. Look here for a brief introduction to the concept of sentence. From m.1 with upbeat there is a two measure basic idea in the tonic (b minor) which is repeated in m.3 with upbeat supported by a iv64 harmony. Because the bass is still on a B natural this can be seen as a pedal four sixth chord (PED64) which would interpret the E and G natural as double neighbour notes to the soprano and alto voices of the tonic chord.[7]Steven G. Laitz, The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis and Listening (4th Ed (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2016), 304-305.

After this we expect a return to the tonic but Haydn decides otherwise. There is a variant of the basic idea in m.5 with upbeat to which is added the V on the second half of m.6, a half cadence (HC). This last bit is 5 beats long and not nearly enough to form a proper continuation (which normally would be 4 measures [or 8 beats] long). Nevertheless it feels like a conclusion of the phrase on the HC (when properly played) be it that it is stopped short on the fifth beat.

The second half of the phrase, starting in m.7, is as mentioned a cadential progression. Starting at the end one can see that from m.11 onwards the bass makes a diatonic stepwise ascend from the third scale degree to the fifth after which the cadential 5-1 follows. The soprano and alto make a 5-1 closure with a small embellishment (second half of m.11). A nice contrary motion which is harmonised with the tonic (i6), predominant (ii6), dominant (V) and tonic (i): a full cadential progression.

In m.7 starts a comparable stepwise bass ascend this time up to the sixth scale degree (the G natural in m.10). Notice that the first violin also makes a stepwise ascending motion (b-c#-d#-e-f#-g). To see this one must realize that the harmonic structural notes are the C# and D# in mm.8-9 and that the D respectively E natural on the first beat are suspensions of (in Schenkerian terms overreaching) tones on the last eighth note of the previous bar.

This parallel stepwise ascending motion in the soprano leads in general to parallel fifth or octaves, not desirable from contrapuntal perspective. But when looking at the position of the chords one understands why that is not a problem here: all chords are in sixth position (first inversion) so the progression is Fauxbourdon like.

There are two exceptions to the Fauxbourdon: the first one being the applied dominant (V43) of the iv6 (e minor) in m.10 which Haydn realizes by raising the third scale degree (the D#). The second one is the vii043 on the second beat of m.10. It is comparable with the half cadence [HC] on the second beat of m.6

Looking at the whole of the expanded cadential progression (mm.7-12fb) we find two times almost the same cadential progression. The first one (mm.7-10fb) ends deceptively on a iv6 on the first beat of m.10. Haydn plays a trick on us by harmonising the fifth scale degree in the bass in m.9 not with a dominant (F-sharp) chord but with the dominant of the deceptive iv6. The next cadential progression starts on the first beat of m.11 (after the vii043) and ends with a faster harmonic rhythm in a full closure (PAC) on the first beat of m.12.

The motives of the primary theme (P)

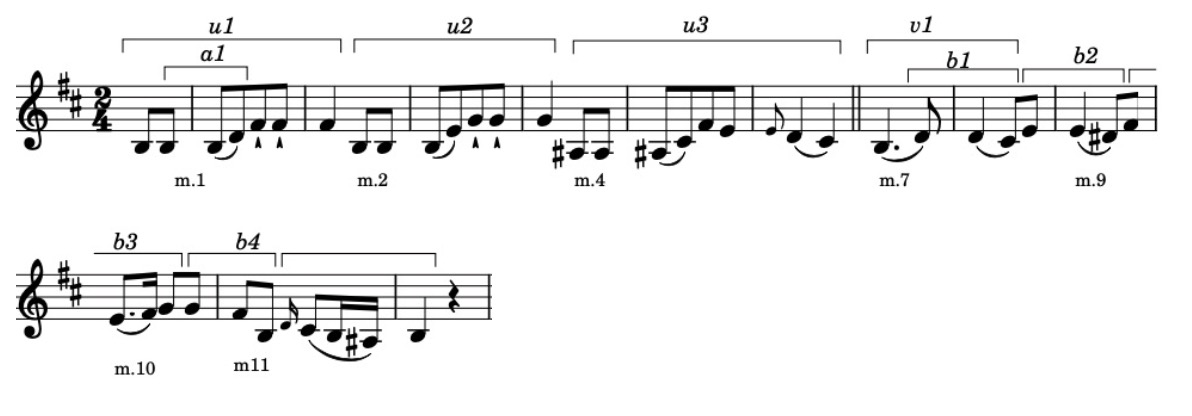

Figure 2 shows the motives of the primary theme.

fig.2 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, motives of the main theme

The motives u1 and u2 are quite similar. Motive u3 has a slight variation, where, in addition, the half cadence (HC) on the second beat of m.6 has been added.

The motives of the expanded cadential progression (mm.7-12fb) are in fact no more than a stepwise ascending figure with in between an incomplete neighbour note.

The TR=>FS or expansion section

Here we enter the section that starts as a transition but fails to lead to a secondary theme (preceded by a medial caesura). The annotated score of this section can be found here.

Terminology

It is perhaps good to first clarify some terminology being used in these types of expositions. The characteristic feature is that the transition keeps expanding and no clear secondary theme can be identified. This means there is no rest point that could end the transition – called medial caesura – and (therefore) no clear beginning of the secondary theme, indeed, there is no secondary theme, according to Hepokoski and Darcy.[8]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 52.

Two terms are being used in the recent literature: the continuous exposition and the three-part exposition.

The continuous exposition

The expression continuous exposition comes from Hepokoski and Darcy in their book Elements of Sonata Theory.[9]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, Chapter 4: The continuous exposition.

They state:

The continuous exposition is identified by its lack of a clearly articulated medial caesura followed by a successfully launched secondary theme.[10]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 51.

Harmonically the progression is the same as in the exposition type where there is a medial caesura and a secondary theme. The transition expands itself and leads to a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in the new key, what would otherwise have been the key of the secondary theme. And the essential expositional closure (EEC) is also considered to be there.

The three-part exposition

The term three-part exposition can be found in the book by James Webster: Haydn’s ”Farewell” Symphony and the idea of classical style.[11]James Webster, Haydn’s “Farewell” Symphony and the idea of classical style: Through-Composition and Cyclic Integration in his Instrumental Music (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 166.

The term three-part exposition implies that there is apparently also an n-part exposition, with n unequal to 3. Indeed there is the two-part exposition. The two-part exposition refers to an exposition with a medial caesura and a secondary theme.[12]See for instance: Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 52.

The two parts are considered to be the primary theme and transition on the one hand (in the tonic) and the secondary theme and the closing section (in the new key) on the other hand. So the “two” in two-part exposition refers mainly to the harmonic structure and not to the various components like primary theme zone, transition, secondary theme and closing section. Then the name would probably have been: four-part exposition.

Webster explains the three-part exposition as follows:

This [the three-part exposition] centers around a long, unstable Entwicklungspartie or “expansion section” in the middle, preceded by a short first group in the tonic and followed by a short, contrasting, piano theme and codetta in the dominant.[13]Webster, Haydn’s “Farewell” Symphony and the idea of classical style, 166.

He adds that the piano theme at the end should be interpreted as a closing theme and not as a second theme. Hepokoski and Darcy would tell you that this so called expansion section is closed with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC), being the essential expositional closure (EEC) in the new key (Webster says dominant which implies he is only talking about a tonic in the major mode). The “three” in three-part exposition refers to the rhetorical aspects of the material and not to the harmonic aspects.

So the “two” in two-part exposition and the “three” in three-part exposition refer to different aspects of the score. Just to keep you awake …

The expansion section

In fact the term expansion section has already implicitly been defined above in Webster’s explanation of the three-part exposition. Hepokoski and Darcy make the definition more explicit in their paragraph on the Continuous Exposition subtype 1, “the more familiar subtype alluded to in the literature on Haydn”.[14]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 52.

They state that:

Following a P [primary theme] idea the composer enters TR [transition] and continues to spin it out in a succession of thematic or sequential modules for most of the rest of the exposition, never pausing for the MC [medial caesura] breath and the subsequent launch of S [secondary theme].[15]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 52.

They then add that this goes on beyond the point where one would expect the MC and the start of S. Apparently Jens Peter Larsen coined this large middle part of the exposition as Entwicklungspartie which was originally translated in English as elaboration section. Later on this changed to expansion section. Hepokoski and Darcy refine the concept of expansion section when talking about their subtype 1 (most applicable to Haydn), which is the subject of the next paragraph.

TR=>FS: Transition becomes Fortspinnung

So Hepokoski and Darcy introduce the concept of TR=>FS to particularise the concept of expansion section. They formulate it as follows:

This section [the expansion section] may now be grounded in a succession of Fortspinnung modules (FS), an [sic] moment-to-moment “spinning-out” of motives (most common in Haydn), or it may be a succession of differing, melodically profiled modular links, more a thematic chain than Fortspinnung proper (as sometimes in Mozart).[16]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 52-53.

The arrow (=>) translates as “becomes”; the Transition becomes a spinning out of motives and leads without a medial caesura or secondary theme to the (perfect authentic) cadence that formally ends the exposition (the EEC: essential expositional closure). Only a closing section can follow.

With all these concepts in mind we may enter the analysis of the expansion section. In what follows I will use the terminology proposed by Hepokoski and Darcy.

An analysis of TR=>FS

Despite the fact that this whole section (TR=>FS, mm.13-51) is regarded as one section a division in three subsections is possible. This is shown in table 3.

Measure

13-32

33-43fb

43-51fb

Subsection

sentential structure

Prinner

cadential area – EEC

Key (relative to b minor)

i – III

III

III – III:PAC

Table 3: layout of the TR=>FS [fb=first beat]

The sentential structure

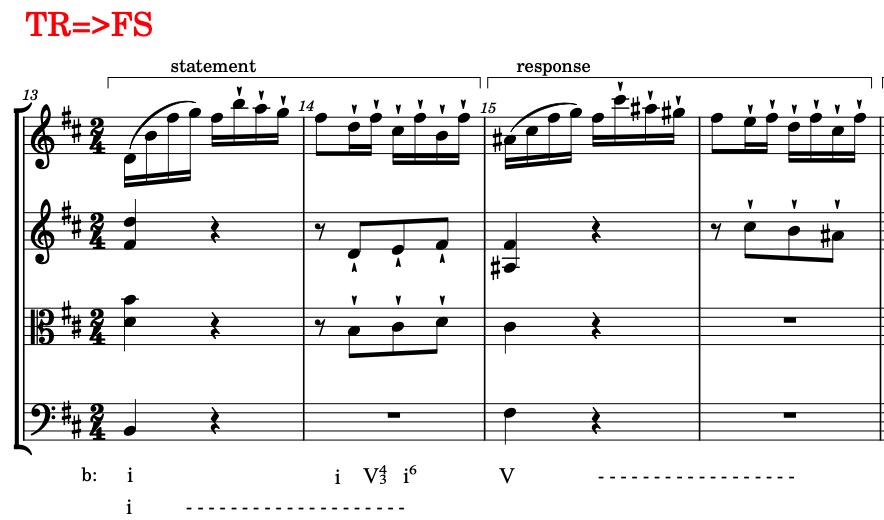

The transition begins with a sentential structure of which the presentation is shown in fig.3. Look here for an introduction to the concept of sentence.

fig.3 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, mm.13-16

The basic idea (mm.13-14) is slightly varied repeated in the dominant (F-sharp major, mm.15-16). So this can be called a statement-response presentation. In mm.17-20 the presentation is repeated.

The motive of the basic idea is clearly inspired by the u-family motives of the primary theme (fig.2). The u-motives are triadic and so is the motive in mm.13-14. Both end on the dominant (F-sharp) and return to the tonic. In the transition the spacing of the triad is open whereas in P the structure is closed. In the transition Haydn added various ornamentations. And of course the placement of the motive in the bar is different. The opening of the movement starts on a weak beat and in the transition the start is on the strong down beat. All in all one can speak of a P-based opening of the TR=>FS section.

Then follows a continuation of twelve measures as shown in fig.4. It starts with a falling fifth sequence [D2(+4/-5)] which ends in m.29. That is why the D major harmony in mm.27-28 belongs to the sequence and should not be interpreted as a cadence in D. The modulation to D major is made in the first copy of the sequence (mm.23-24), D major being the mediant and relative major of b minor.

fig.4 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, mm.21-32

Measures 29 and 30 with the E natural (the second scale degree) respectively the C-sharp (the seventh scale degree) in the bass I would interpret as two neighbour cords that embellish the I (D major). The tonic is prolonged for two bars (mm.31-32) that are also an introduction or lead-in to the next phrase.

The Prinner

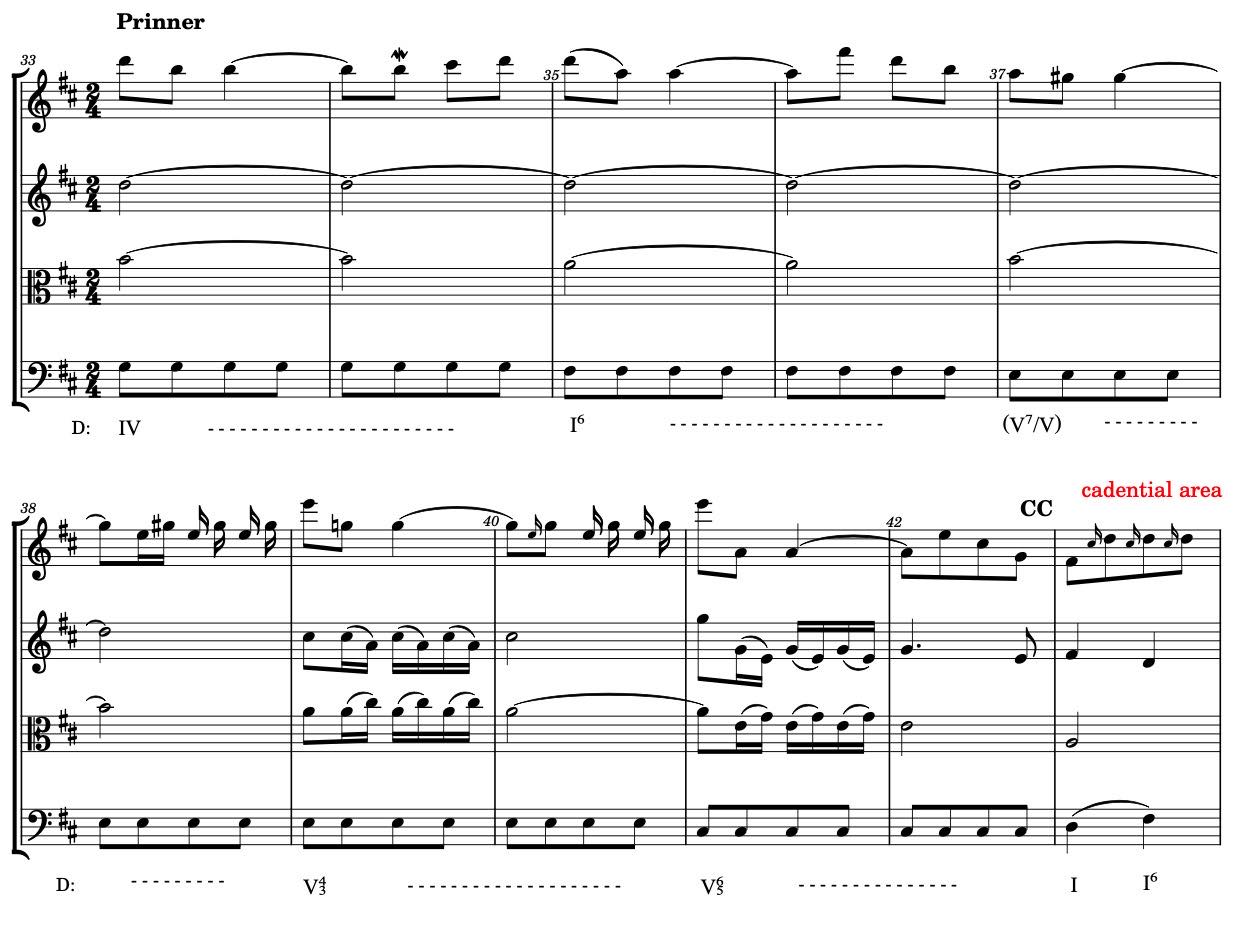

This next phrase is shown in fig.5.

fig.5 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, mm.33-43

Haydn introduces a new two-bar motive (mm.33-34) which is repeated with (slight) variations four times after its introduction. This is the point where one can get for the first time an inkling that this is not an ‘ordinary’ two-part exposition. There has been no pause (like a medial caesura) but nevertheless a new motive is introduced. A secondary theme? There are a couple of arguments against this. First of all the phrase that surely on hearing its beginning sounds like a transition (mm.13-32), closes with a weak cadence in III (D major) in mm.30-31. Then without any restpoint and with a continuation of the bass line the new motive starts on the IV of D major (m.33). A second theme is supposed to start in D major (the III of the tonic of the movement), especially in the early classical style.

But then there is another – perhaps surprising – argument. As shown in fig.5 the bass follows a stepwise descending line in D major from the fourth scale degree onwards (m.33). The soprano (first violin) follows on a third plus two octaves above the bass. A Galant style schemata can again be recognised in this progression[17]Menno Dekker was kind enough to bring this to my attention. as defined in Robert O. Gjerdingen’s book Music in the Galant Style.[18]Robert O. Gjerdingen, Music in the Galant Style (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 2007).

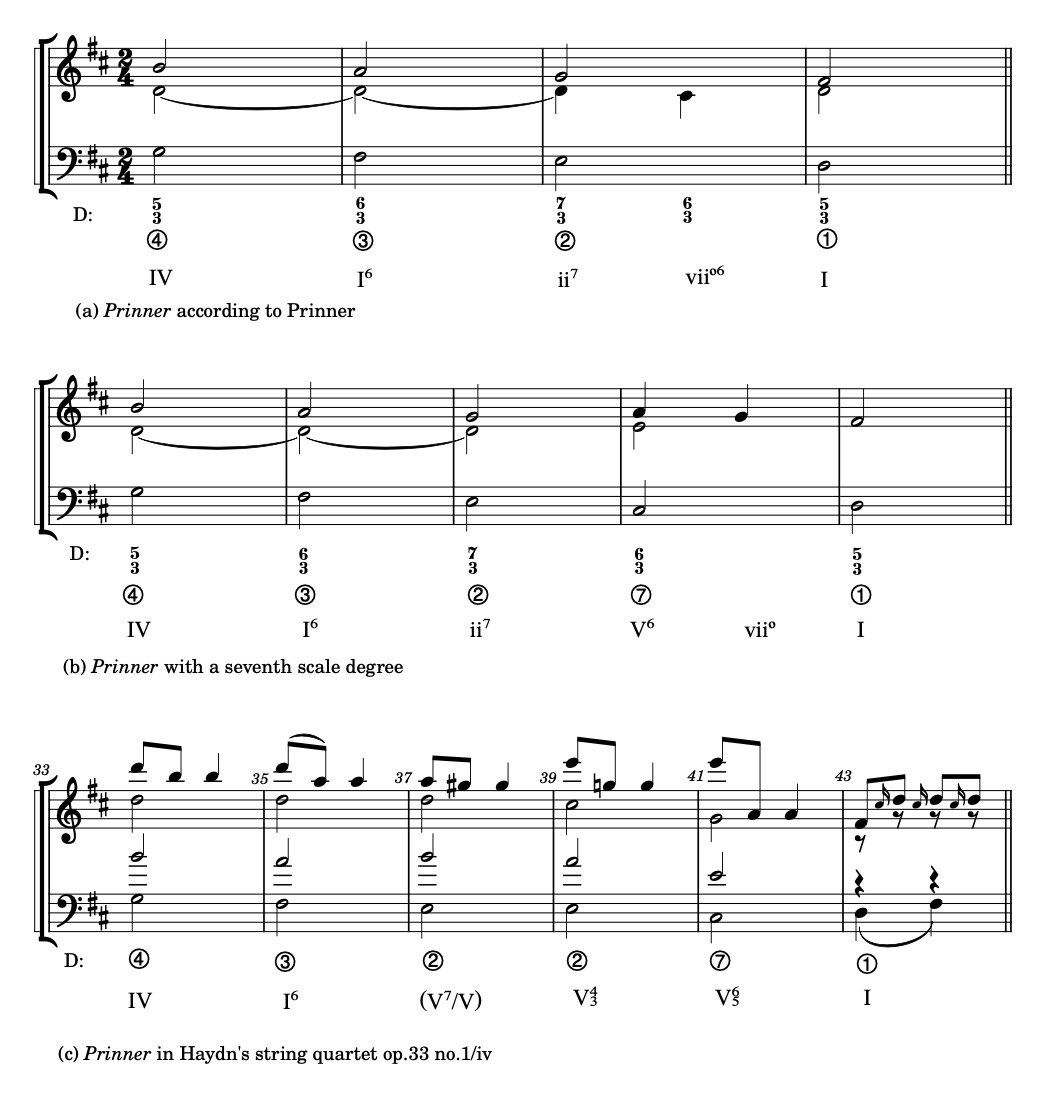

Find a short introduction to Galant schemata here. This time it is about the pattern Gjerdingen has dubbed Prinner[19]Gjerdingen, Music in the Galant Style, 45., after the seventeenth-century music pedagogue Johann Jacob Prinner (1624-1694).

Figure 6a shows the Prinner as cited by Gjerdingen from Johann Jacob Prinner.[20]Gjerdingen, Music in the Galant Style, 46. Clearly recognisable is the stepwise descending bass and the parallel tenth in the soprano. Figure 6b shows a Prinner with an added seventh scale degree just before the final tonic. And finally figure 6c shows the phrase as Haydn wrote it in the string quartet under consideration. Note that I have combined the two bars of the motive into one bar. In mm.37-38 Haydn inserts a chromatic passing note in the soprano (the G-sharp) which leads to an applied dominant of V instead of the ii in the other examples. A raised third in the ii of a major key becomes an applied dominant of V of that key.

fig.6 Galant Schemata: the Prinner

As Gjerdingen explains in his introduction to chapter three of his book the Prinner was a riposte (to be translated as: a pithy reply) to an opening gambit.[21]Gjerdingen, Music in the Galant Style, 45.

So Haydn used a Galant schemata that was used as the answer to an opening phrase. That can hardly mean that he intended to start a secondary theme here. The conclusion must be that we can confidently follow Hepokoski & Darcy when they say that this movement is a locus classicus of a continuous exposition.[22]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 54.

The cadential area

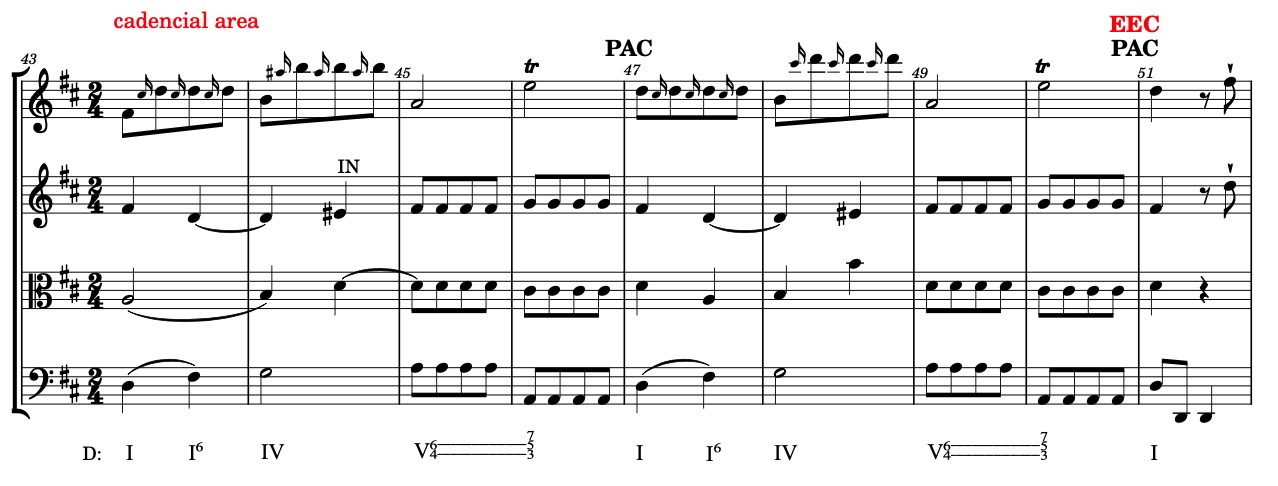

The third subsection of the TR=>FS section is a cadential progression which is shown in fig.7.

fig.7 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, mm.43-51

It is a straightforward cadence but thanks to the grace notes very lively. The first beat of m.51 is the end of the TR=>FS section and the perfect authentic cadence (PAC) that ends it is at the same time the essential expositional closure (EEC).

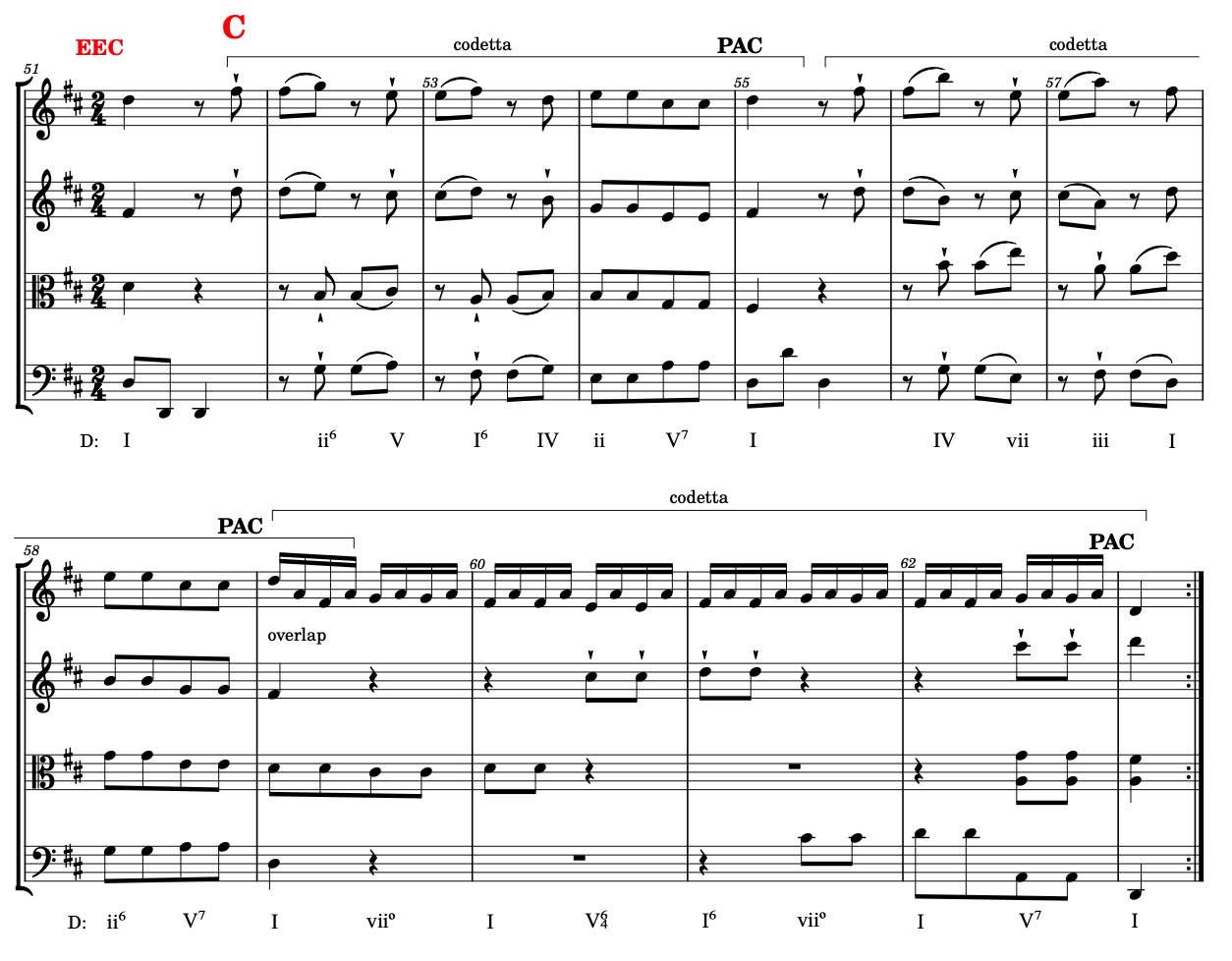

The closing section

The closing section is shown in fig.8. It consists of three codettas the first one of which uses slightly modified fragments of the motives from the primary theme (fig.2, motive a1). This codetta is repeated with slight variations (m.56 with upbeat – m.59 first beat).

fig.8 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, mm.51-63

The material of the third codetta reminds one of the material from the TR=>FS section. Harmonically it is a prolongation of I (D major) with a pedal on A natural in the first violin. All codettas confirm the key of D major with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC).

This ends the analysis of the exposition of the fourth movement of the Haydn’s string quartet in b minor, op.33 no.1.

Notes

| ↩1 | John Daverio, Robert Schumann: Herald of a “New Poetic Age” (New York etc.: Oxford University Press, 1997). |

|---|---|

| ↩2 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 251. |

| ↩3 | Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 52. |

| ↩4 | Floyd Grave and Margaret Grave, The string quartets of Joseph Haydn (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 199 and 201. |

| ↩5 | Charles Rosen, The classical style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven (London: Faber and Faber, 1971), 119. |

| ↩6 | William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998), 61. |

| ↩7 | Steven G. Laitz, The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis and Listening (4th Ed (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2016), 304-305. |

| ↩8, ↩14, ↩15 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 52. |

| ↩9 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, Chapter 4: The continuous exposition. |

| ↩10 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 51. |

| ↩11 | James Webster, Haydn’s “Farewell” Symphony and the idea of classical style: Through-Composition and Cyclic Integration in his Instrumental Music (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 166. |

| ↩12 | See for instance: Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 52. |

| ↩13 | Webster, Haydn’s “Farewell” Symphony and the idea of classical style, 166. |

| ↩16 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 52-53. |

| ↩17 | Menno Dekker was kind enough to bring this to my attention. |

| ↩18 | Robert O. Gjerdingen, Music in the Galant Style (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 2007). |

| ↩19 | Gjerdingen, Music in the Galant Style, 45. |

| ↩20 | Gjerdingen, Music in the Galant Style, 46. |

| ↩21 | Gjerdingen, Music in the Galant Style, 45. |

| ↩22 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 54. |

Recent Comments