Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1: an analysis of the recapitulation of the fourth movement

Last updated on September 18th, 2025 at 11:31 pm

Table of contents

Introduction

As I was working on the analysis of Schumann’s piano quartet in E-flat major, op.47, I read the book by John Daverio on Schumann.[1]John Daverio, Robert Schumann: Herald of a “New Poetic Age” (New York etc.: Oxford University Press, 1997).

A remarkable feature of the piano quartet is that the exposition has no second theme and that the articulation of the dominant is late in the exposition (find my analysis of the first movement of the piano quartet here). Daverio compares the way in which Schumann and Haydn handle the sonata form and remarks “Similarly, Haydn’s teleological sonata forms […] find a counterpart in the delayed articulation of the dominant that characterizes the exposition of the first and last movements of Schumann’s Opus 41, no 2 [string quartet]”.[2]Daverio, Robert Schumann, 251.

Previously this made me investigate Schumann’s string quartets the posts of which can be found here.

The fact that no second theme can be found in the exposition indicates a continuous or three-part exposition. Hepokoski and Darcy mention the finale of Haydn’s string quartet in b minor, op.33 no.1 as a typical example of a continuous exposition.[3]Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 52. This led to a closer examination of this string quartet and so I started a small series on it.

This post is the third post in the series and is about the recapitulation of the last movement: Finale – presto. There are also posts on the exposition and the development of the same movement.

As always I want to thank Menno Dekker – my former professor at the conservatory of Amsterdam – for the very useful discussions I have had with him. It keeps improving my understanding of music and more particular music analysis. Our relation has grown into a genuine friendship with the music theory and analysis as a perpetual source of inspiration.

Historical context

Haydn wrote the opus 33 group string quartets in 1781, nine years after the previous group: opus 20. The character is quite different and they are seen as a turning point in western music history and as start of the classical style. Whereas the op.20 quartets lean more towards the learned (baroque) style, the op.33 quartets are more playful and quite accessible. One of the reasons mentioned for this change is that Haydn’s contract with the Esterházy’s had been revised and Haydn was free to distribute his music as he wished. This meant that Haydn aimed for a larger public that was more accustomed to comic opera, street songs and dance music of the time.[4]Floyd Grave and Margaret Grave, The string quartets of Joseph Haydn (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 199 and 201.

Charles Rosen mentions that in the nearly decade that separated the two opus groups Haydn was much engaged with comic opera both in writing and in producing them at the Esterházy court. What he learned in that period he used in writing the quartets op.33.[5]Charles Rosen, The classical style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven (London: Faber and Faber, 1971), 119.

The op.33 quartets have various nicknames among which the Gli Scherzi is probably the most well known. It comes from the fact that the dance movements have been named Scherzo (previously Minuet). Scherzo means also joke in Italian and the fun factor is quite present in the op.33 quartets.

Practical information

In this text a lot of references are made to the score of the fourth movement. This is done by means of the measure number. Ideally you have a score with measure numbers at your disposal. A score can easily be downloaded from IMSLP.

In general notes on analysis you can find some remarks on abbreviations, notation and concepts. Some books that I have been consulting can be found in consulted literature. At least all references made to literature in the notes should relate to entries in the consulted literature. The music examples are made in Musescore 4.

Look here for my use of Sonata Form terminology.

Notational convention for major and minor keys

As for a notational convention of major and minor keys: I will use capitals for major keys and lower-case letters for minor keys. For major keys I will often add the word major and for minor keys the word minor, but in music examples and diagrams the words major and minor will in general be omitted. So B major or B for B major and b minor or just b for b minor.

Most suitable devices

Finally it must be mentioned that although automatic adjustments are made to view these posts on tablets as well as mobile phones, they can best be accessed on a computer/laptop. The reason being that there are various tables and lists (like abbreviations) of which the columns will appear one beneath the other (especially on a mobile phone). If that is the case the coherence will be lost.

Haydn: the string quartet in b minor, op.33 no.1

Fourth movement: Finale – Presto

Global structure

The Finale is in sonata form and contains the following elements:

Measure

109sb-137

137-175fb

109sb-194fb

Section

Exposition

Development

Recapitulation

Key (relative to b minor)

i – III

III – V

i

Table 1: layout of the first movement [fb=first beat; sb=second beat]

The recapitulation

The recapitulation contains the following elements (ESC stands for Essential Structural Closure):

Measure

109sb-137

137-175fb

174-175

176wu-194fb

Section

Primary theme (P)

TR=>FS or expansion section

ESC

Closing Section

Key (relative to b minor)

i

i

i:PAC

i

Table 2: layout of the Recapitulation [fb=first beat; sb=second beat; wu=with upbeat]

As the recapitulation has the same structure as the exposition there is no secondary theme and after the (varied) primary theme follows the (TR) ==> Fortspinnung (FS) or expansion section of the recapitulation. Look here for some remarks on the terminology.

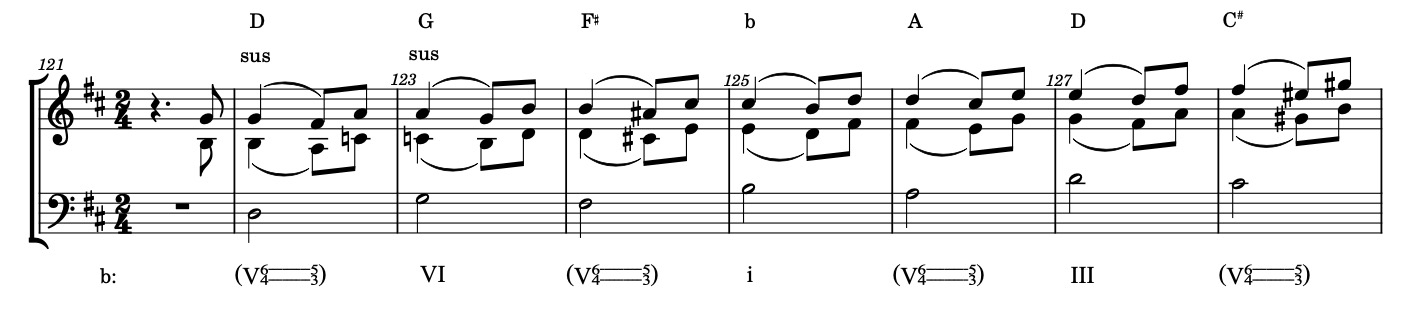

The primary theme in the recapitulation

Figure 1 shows the primary theme. Comparing this with the first theme from the exposition (exposition fig.1), the first thing that stands out is the length of the theme. In the exposition the primary theme is 12 and a half measures long, in the recapitulation it is 27 and a half or 28 measures long, depending on the interpretation of mm.135-137fb.

The first phrase (mm.109sb-115) is exactly the same as the antecedent of the primary theme in the exposition.

fig.1 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, recapitulation, mm.109sb-137

The next phrase starts in m.116 and lasts till m.137 where the TR=>FS expansion section starts. Haydn really expands the cadential progression here!

I think it is helpful to distinguish three parts is this phrase as shown in table 3.

Measure

116-120

122wu-128

129-137fb

Part

1: cadential progression

2: ascending third sequence

3: cadential progression

Key (relative to b minor)

i6 – iv6

iv6 – V/V

V/V – i

Table 3: parts in the second phrase of P in the recap [fb=first beat, wu=with upbeat]

P, second phrase, part 1

This is the part that largely corresponds to the expanded cadential progression in the first theme in the exposition (exposition fig.1, mm.7-12fb). It starts to deviate in m.119. The corresponding m.10 in the exposition is the arrival on the deceptive iv6. It is followed by the cadential progression towards the perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in m.12 that closes P in the exposition.

Here, in the recapitulation, m.119 has a suspension in the first violin that resolves to the same iv6, but only in the next measure. This is in fact an augmentation of the suspension motive b1 in the previous measures (exposition, fig.2). Together with the more than two beats rest that follow an enormous tension is created. How is this resolved? There are another fifteen measures to go before P is over.

P, second phrase, part 2

Part 2 (running from m.122 with upbeat to m.128) is interesting. Melodically it is a continuation of the b1 motive found in the part 1, now alternately played by the first and second violin. The viola always plays a sixth below the melody voice. In fact m.120 of the previous part can be seen as the start of the melodic sequence.

Although the melody is a continuation of the second subsection, the bass follows a different path. It leaps up a fourth and then descends with a second. Harmonically this leads to an ascending third sequence by first leaping up a fourth and then descending a second: A3(+4/-2). I am talking not only about the bass but also about the chords. Apart from the V64 suspension they are all in root position, therefore the bass alone follows the same pattern as the chords in the sequence. Figure 2 shows a reduction of the passage.

fig.2 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, reduction of mm.121-128

The first and second violin are merged into one voice. The viola is shown one sixth below this voice in the same (first) stave. The second stave shows the bass as half notes and without the octave leap. Taking into account that the e minor chord in m.120 can also be seen as the start of the harmonic sequence the ascending third chords are as follows:

e (iv) – G (VI) – b (i) – D (III)

The roman numerals relative to b minor are added between brackets. In between are always the applied dominants. Look how ingenuously Haydn used the suspension figure of mm.117-118 (the b1 motive) to create the sixth-four suspension for the applied dominants in m.122, 124 and 126. Of course the parallel sixths in the viola are necessary to accomplish that. The subsection ends on a C-sharp chord that should be interpreted as the dominant of the dominant (V/V) of b minor.

P, second phrase, part 3

This part runs from m.128 to m.137fb. For your convenience, it is shown again in fig.3. Measure 128 is an elision between the second and third part. As mentioned in part 2 it is the dominant of the dominant, i.e. the C-sharp chord is the dominant of F-sharp which is the dominant of b minor. Where is the F-sharp chord? It is not there, but in mm.134sb-136 there is an a-sharp diminished seventh chord, being the seventh of b minor.

fig.3 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, mm.128-137

This chord can be seen as the dominant (ninth) chord of b minor, without the root and certainly has a dominant function. The whole progression of variants of the C-sharp chord (mm.128-132fb) is between brackets because they are the applied dominant of F-sharp with the 64-chords as ornamenting neighbours. Measure 129 is an incomplete dominant seventh chord (the third is missing) which passes by way of a V64 chord to the C-sharp triad in root position.

Look here for an explanation of the V64 chord as neighbour of a dominant chord. It concerns variant (b). Here the two neighbour notes (the A natural and the F-sharp) are diatonic because the tonic is in the minor mode. In fact the V64 on the first beat of m.130 is here a passing chord (P) – and not a neighbour chord – because of the start on a dominant seventh chord, the voice exchange that Haydn applies and the introduction of the missing E#.

The second beat of m.132 is a predominant ii0 and then, again by way of a passing chord (this time a VI6 chord, first beat of m.134) the vii07 is reached.

Now here we reach an interesting point. Should we interpret the vii07 chord in mm.135-136 as an endpoint and therefore assign it a half cadential function? Or, does it have a dominant function in a cadential progression that leads to the tonic b minor in m.137 and is therefore the first beat of m.137 an elision with the TR=>FS section?

The half cadential interpretation was the first that came to my mind, also inspired by the conclusion of the first theme in the exposition (exposition, fig.1, mm.11-12). There it ends with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) followed by a pause in three voices which is a real closure before the TR=>FS section starts. This interpretation raises another question: can a vii07 chord be seen as a half cadence (HC)? After reading Poundie Burstein’s contribution in What is a cadence?[6]Poundie Burstein, “The half cadence and related analytic fictions”, in What Is a Cadence? : Theoretical and Analytical Perspectives on Cadences in the Classical Repertoire, ed. Markus Neuwirth and Pieter Bergé (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2015). I decided to ask his opinion on this matter. And it was he who suggested the second interpretation: the vii07 chord in mm.135-136 is part of a cadential progression that ends with the tonic b minor chord in m.137 which is at the same time the start of the TR=>FS section. The argumentation being that if the melodic line that starts in m.129 were to be continued in m.136 then a chord as shown in m.137 is expected with a D5 natural in the first violin. What Haydn wrote is a suspension in m.136 and then the expected chord occurs in m.137 but with a D4 in stead of a D5 in first violin.[7]I am indebted to Poundie Burstein who kindly gave me this suggestion and explanation. It is as if someone held his breath for a moment and then continued anyway.

It is interesting to listen to recordings of this string quartet. Most quartets do play quite an ending on m.136. Cuarteto Casals gives a convincing interpretation in line with the second view, especially in the repetition of the second part of the last movement.[8]Joseph Haydn, String Quartets op.33, Cuarteto Casals, recorded 2008, harmonia mundi HMG 502022.23, compact disc.

This ends the Primary theme (P) in the recapitulation. Quite an elaborate version of the pretty compact first version of the main theme. I think Haydn is playing with the expectations of the listener here. First there is the stretched deceptive ending in mm.119-120 followed by the long pause in mm.120-121. It reminds one of what I called “the top of a rollercoaster moment” in the core, part 2 of the development, also on a iv6 in b minor.

In the exposition what followed was the cadential progression towards the PAC in mm.11-12. So the listener might expect something of the kind. But instead the ascending third sequence starts that leads to the dominant of the dominant (C-sharp) in m.128. So now do we get the long-awaited cadence? No! Haydn first lingers on the C-sharp chord for more than four bars and then proceeds to a predominant ii0 (m.132). But it is not followed by the dominant (F-sharp chord) but by the weaker and prolonged vii07 and then, without any warning, the TR=>FS section bursts out.

Haydn pulls a long nose and makes fun of us several times. A nice example of the much mentioned humor in the op.33 string quartets.[9]In Floyd and Margaret Grave’s book on the Haydn string quartets there are two paragraphs in the chapter on the op.33 string quartets which address these elements: Elements of Wit and Humor and Thwarted expectation. The final movement of the string quartet op.33 no.1 is however not mentioned as an example. Floyd Grave and Margaret Grave, The string quartets of Joseph Haydn, 213-218.

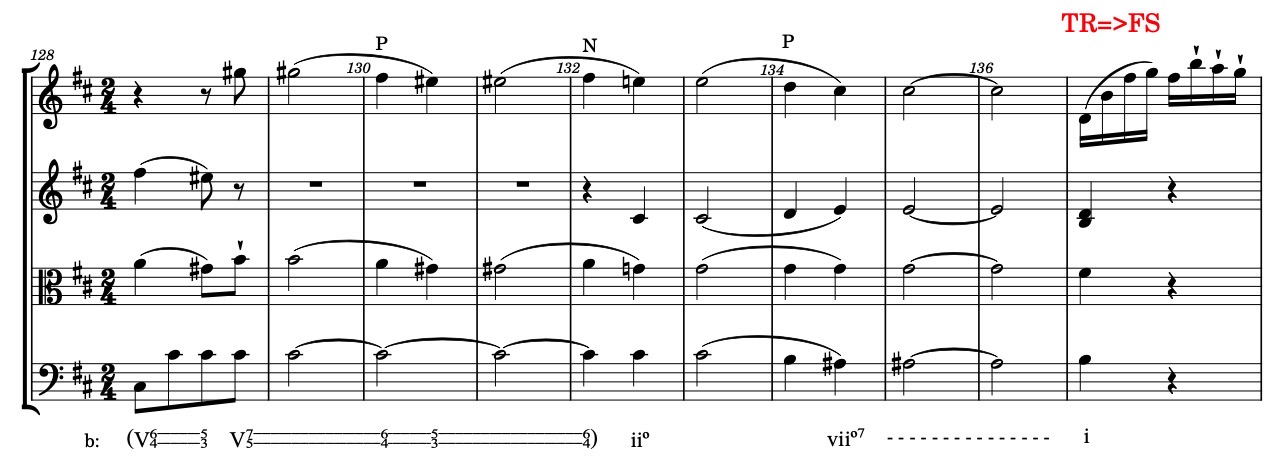

The TR=>FS section in the recapitulation

Whereas the parallel section in the exposition modulates to D major (the relative major of b minor) and leads to a closure with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in that key (exposition, fig.7), we expect that in the recapitulation there will be no modulation and the section will confirm the tonic of the movement (and piece), b minor. And so it is. It is interesting to look at the way Haydn achieved this. A down loadable PDF of this section with my annotations can be found here.

Perhaps the first thing to notice is that both sections (the one in the exposition and in the recapitulation) have exactly the same number of measures: 39. And as in the exposition the same division in subsections can be made in the recapitulation. This is shown in table 4. ESC stands for Essential Structural Closure. I’ll come to that.

Measure

137-156

157-167fb

167-175fb

Subsection

sentential structure

“Prinner” theme

cadential area – ESC

Key (relative to b minor)

i – V2

i

i – i:PAC

Table 4: layout of the TR=>FS in the recapitulation [fb=first beat]

Measure 137 corresponds to m.13 in the exposition, so any measure with number n in the TR=>FS section in the recapitulation corresponds to measure n-124 in the exposition.

The sentential structure

The sentential structure (mm.137-156) in the recapitulation corresponds to mm.13-32 in the exposition. The first twelve measures are in fact exactly the same. It concerns first of all the presentation of the sentence-like structure and its repetition. The first four measures of the continuation are identical also. As of m.149 things start to deviate. Figure 4 shows the continuation (which corresponds to fig.4 of the exposition). An additional measure is shown (m.157) to make clear the connection with the next section.

fig.4 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, mm.145-157

The corresponding measure of m.147 in the exposition (m.23) is the pivot chord in the modulation to D major (the e minor chord is a iv in b minor and a ii in D major). Furthermore in the exposition there is a descending fifth sequence starting in m.21. In the recapitulation the start of the sequence is there (because the measures are identical) but after the second step in the sequence (the e minor chord in mm.147-148) the sequence is not continued. Instead Haydn moves to the C-sharp dominant seventh chord in mm.149-150. Then follows a pedal on F-sharp which is the bass note of an F-sharp chord alternating with the neighbour (the V64 in mm.152-154). Look here for some explanation on these neighbour chords. The F-sharp chord is of course the dominant of b minor which is reached in m. 157 (be it in first inversion). This is all summarised in fig.5.

Now can we find any logic in the harmonic progressions from m.21 to m.33 and the parallel measures from m.145 to m.157? Or: what plan did Haydn have in mind to make a recapitulation which remained in b minor instead of modulating to III, D major, but of course with the similar thematic/motivic material?

fig.5 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, comparison of TR=>FS in exposition and recapitulation

Perhaps the first thing to notice is that whereas the Prinner-theme in the exposition starts on G major (m.33), the IV of D major (the prevailing key), the corresponding theme in the recapitulation starts in b minor. So Haydn decided to stay close to the home key of the movement and not to make a foray into, for instance, the iv of b minor (e minor).

The G major of mm.33-34 is the result of the Prinner voice leading (see fig.6 of the exposition). In the recapitulation the theme starts in b minor which is the prevailing and home key of the movement.

Because Haydn starts the “Prinner theme” in b minor (in first inversion) he could not use the fourth scale degree as bass note in m.157. For a tonic triad he had only three options. The fifth (F-sharp) drops out for obvious reasons. Of the two remaining possibilities the third is closest to the four of the original Prinner, and that is the one he chose (that is also why the b minor chord is in first inversion). How did he handle that?

Well, my hypothesis is that he tried to stay close to what he did in the exposition but with a different outcome. The D major from m.27 onwards has a special meaning as the second key of the sonata form. Looking forward at the IV (G major) in mm.33-34, we can however discover a fifth relation. It certainly is not a dominant-tonic relation but it is a falling fifth.

Now look at the recapitulation. The prolonged F-sharp chord (mm.151-155) can only be seen as the dominant of b minor but happily enough produces the same fifth relation with the b minor to come by nature of its function. Haydn uses an intermediate step in both cases: the I6 in the exposition and the V2 in the recapitulation.

Although the functions of the D major and F-sharp major chords are completely different in their respective contexts, the harmonic progression they produce is quite similar due to the different harmonisations of the start of the “Prinner theme”.

Remains to see how these chords are reached. Figure 6 gives a reduction of the harmonic progression up to the D major respectively F-sharp.

fig.6 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, harmonic progressions in exposition and recapitulation

Measures 23-24 and mm.147-148 are identical; in m.25 a descending fifth sequence is continued towards D major in m.27. In the recapitulation however Haydn makes a chromatic alteration in m.149 (the raised E and G) to form the C-sharp dominant seventh chord in first inversion. This is exactly the point where the difference is made. The C-sharp dominant seventh chord proceeds to the F-sharp chord (so the C-sharp dominant seventh chord can be seen as the dominant of the dominant (V/V) of b minor) that is sustained for five bars and is embellished with the V64 chords. Of course this is also a falling fifth progression but because of the (weak) arrival on the first inversion of the tonic b minor the feeling of a cadential progression is stronger then in the exposition.

The “Prinner theme”

Figure 7 shows the recap-version of what was called the Prinner in the exposition.

fig.7 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, “Prinner theme” in the recapitulation.

The same pattern is followed as in the exposition: the two bar theme is repeated four times with variations. The theme is not exactly the same as in the exposition. A reason might be found in the slightly altered harmonic scheme. This is shown in fig.8.

fig.8 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, comparison of the “Prinner-theme” in the exposition and recap

The Prinner theme in the exposition started with the fourth scale degree as bass note (m.33) and then followed the Prinner scheme onto m.43 (with an applied dominant instead of a iiø7). In the recapitulation the theme starts on the third scale degree and than has a more prolonged second scale degree (mm.159-164). This is harmonised with a iiø7 which fits actually better in the Prinner scheme. As of m.41 respectively m.165 the harmonic progression is the same.

So Haydn varies the theme and the harmonic progression but stays close to the original idea. In the recapitulation it is more difficult to map the second subsection onto the Prinner because the bass on the fourth scale degree appears before the theme starts (m.156). Nevertheless the idea is the same.

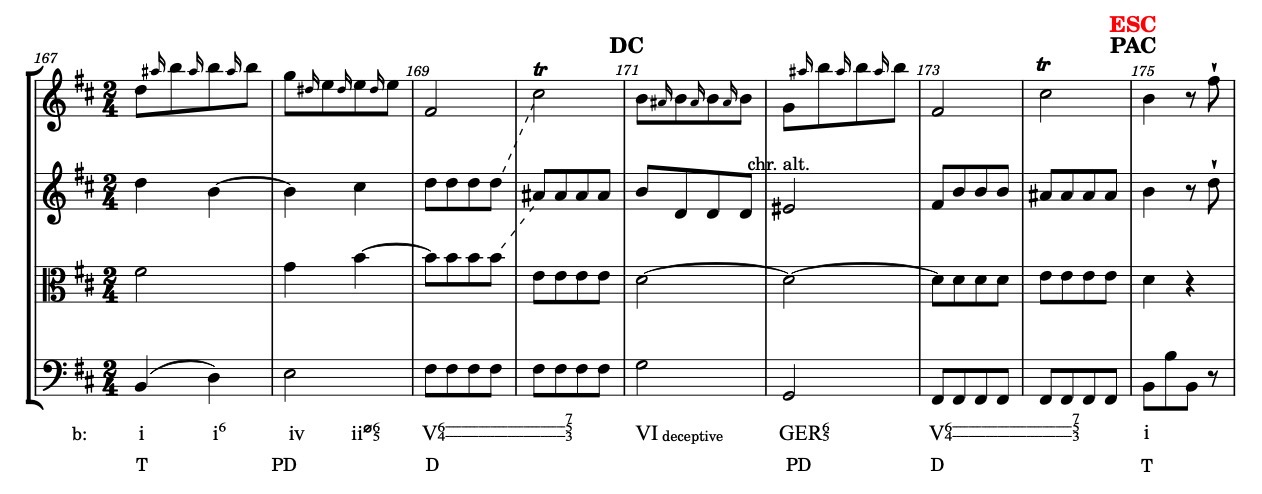

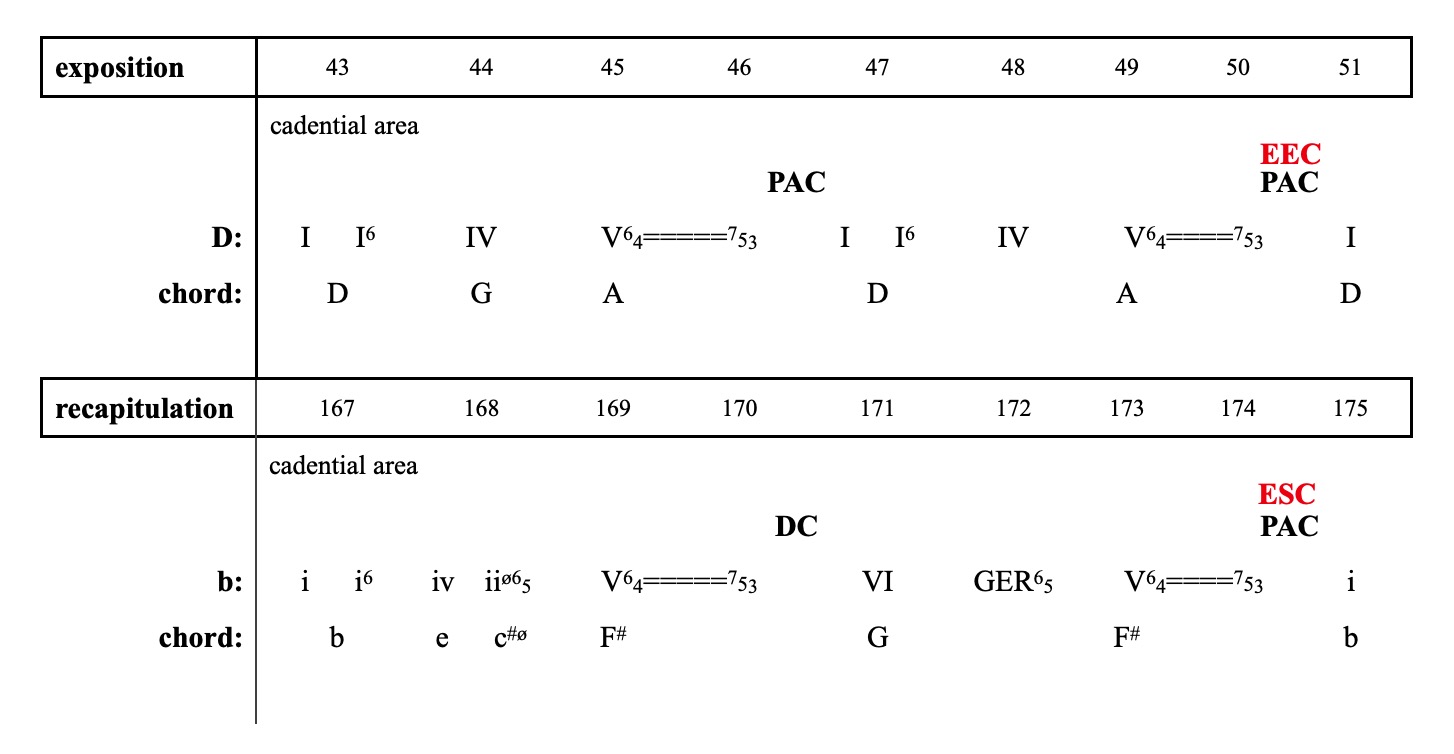

The cadential area

The third subsection is shown in fig. 9.

fig.9 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, recapitulation: TR=>FS: cadential area

This cadential area is very similar to the corresponding subsection in the exposition, but transposed one minor third down (from D major to b minor). The main difference is the cadence in mm.170-171: in the recapitulation it is a deceptive cadence (DC) whereas in the exposition it is a perfect authentic cadence (PAC). This is summarised in the following figure (fig.10).

fig.10 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, comparison of the cadential in the exposition and recap of TR=>FS

In m.168 Haydn starts with the same predominant as in the exposition (IV respectively iv), but adds the second scale degree on the second beat in the second violin and so it becomes a iiø65. G major pops up again in m.171, but this time as the deceptive VI of b minor. Measure 172 also has a different predominant: an augmented sixth chord (#ivDD65 or GER65). It is one of the chords with a double leading tone to the fifth scale degree; here these leading tones are G natural (a lowered 6) and the E-sharp (a raised 4), both leading to F-sharp, the dominant of b minor.

The PAC in mm.174-175 functions as the Essential Structural Closure (ESC). This concept is introduced by Hepokoski and Darcy in their book Elements of Sonata Theory.[10]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 232-233. It is the analogue of the Essential Expositional Closure (EEC) in the exposition. The EEC establishes and confirms the second key (here: D major) in the exposition of a sonata form movement. The ESC brings the final stabilisation and confirmation of the tonic key. According to Hepokoski and Darcy “The attaining of the ESC is the most significant event within the sonata.”[11]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 232.

The Closing section

The closing section is shown in fig.11. It broadly follows the structure of the closing section in the exposition with one exception: between the second and third codetta there has been inserted a fourth one that starts with the opening motive (m.183sb) and is headed towards the cliffhanger in m.187: a vii07 of the dominant. This is a similar construction as we saw in at the end of the core part 1 of the development (mm.87-89fb) and at the end of the primary theme (P) in the recapitulation (mm.135-136). It then finishes with a cadential progression towards the perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in mm.188-189.

fig.11 Haydn: string quartet op.33 no.1, iv, recapitulation: closing section

Notice that the start of the first codetta (mm.176 with upbeat – 177) is exactly the same as the first codetta of the closing section in the exposition. In the exposition the prevailing key is D major whereas in the recapitulation it is b minor. Therefore the first chord in the exposition is a ii6 and the same chord is a iv6 in the recapitulation. After this the codetta in the recapitulation continues differently to make the cadence in b minor possible.

The last codetta resembles very much the last codetta of the exposition: an ornamented tonic with one final cadence with material that reminds one of the TR=>FS section. So the home key is confirmed with four cadences.

This ends the analysis of the recapitulation and with it that of the whole fourth movement.

Notes

| ↩1 | John Daverio, Robert Schumann: Herald of a “New Poetic Age” (New York etc.: Oxford University Press, 1997). |

|---|---|

| ↩2 | Daverio, Robert Schumann, 251. |

| ↩3 | Hepokoski, James A, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 52. |

| ↩4 | Floyd Grave and Margaret Grave, The string quartets of Joseph Haydn (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), 199 and 201. |

| ↩5 | Charles Rosen, The classical style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven (London: Faber and Faber, 1971), 119. |

| ↩6 | Poundie Burstein, “The half cadence and related analytic fictions”, in What Is a Cadence? : Theoretical and Analytical Perspectives on Cadences in the Classical Repertoire, ed. Markus Neuwirth and Pieter Bergé (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2015). |

| ↩7 | I am indebted to Poundie Burstein who kindly gave me this suggestion and explanation. |

| ↩8 | Joseph Haydn, String Quartets op.33, Cuarteto Casals, recorded 2008, harmonia mundi HMG 502022.23, compact disc. |

| ↩9 | In Floyd and Margaret Grave’s book on the Haydn string quartets there are two paragraphs in the chapter on the op.33 string quartets which address these elements: Elements of Wit and Humor and Thwarted expectation. The final movement of the string quartet op.33 no.1 is however not mentioned as an example. Floyd Grave and Margaret Grave, The string quartets of Joseph Haydn, 213-218. |

| ↩10 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 232-233. |

| ↩11 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 232. |

Recent Comments