Beethoven piano trio op.11: an analysis of the development

Last updated on February 15th, 2025 at 12:49 pm

Table of contents

Introduction

The oeuvre of Beethoven is commonly subdivided in three periods:

- The early period: 1770-1801- youth in Bonn and first decade in Vienna

- The middle period: 1802-1814

- The late period: 1815-1827

As the trio op.11 is written in the beginning of 1798 (or the end of 1797) it belongs to the early period. Beethoven lived in Vienna at the time and the trio is dedicated to countess Maria Wilhelmine von Thun und Hohenstein who was a patron of Beethoven (as she was of Mozart). She was famous for her music salons and a fine pianist herself.

The trio is scored for clarinet or violin, cello and piano. In the analysis I will use the clarinet version.

The nickname Gassenhauer for this trio originates from the final movement, in which Beethoven composed a series of variations on a popular tune of the time. This tune comes from the opera L’Amor Marinaro written by Joseph Weigl (1766-1846), and the song itself is titled “Pria ch’io l’impegno” (which means: “Before I go to work”).

In the Viennese dialect, a “Gassenhauer” referred to a song that was so popular that it was sung or played everywhere on the streets (in the “Gassen”). It was essentially a “street tune” that people in the city would often hear.

Although Beethoven, especially in his early period, was firmly rooted in the classical style, there are already signs during this period that he introduced style-foreign elements into his music. In his book Bach’s Cycle, Mozart’s Arrow, Karol Berger goes so far as to say that two different ontological worlds can be discovered in some of Beethoven’s music. [1]Karol Berger, Bach’s Cycle, Mozart’s Arrow: An Essay on the Origins of Musical Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), Postlude. His first example concerns the piano sonata in C major, op.2 no.3 which was written as early as 1795, i.e. three years before this trio. In this sonata there are great surprises that disrupt the flow of the music, only to return to that original flow as if nothing has happened. I tried to look at the present trio with this in mind. It is difficult to say if we can speak of two different worlds in this movement but there are certainly surprises and disruptions. I will point them out on the way through this movement.

This post is about the development of the first movement. The post on the exposition can be found here.

As always I want to thank Menno Dekker – my former professor at the conservatory of Amsterdam – for the very useful discussions I have had with him. It keeps improving my understanding of music and more particular music analysis. Our relation has grown into a genuine friendship with the music theory and analysis as a perpetual source of inspiration.

Practical information

In this text a lot of references are made to the score of the piano trio. This is done by means of the measure number (always within the first movement). Ideally you have a score with measure numbers at your disposal. A score can easily be downloaded from IMSLP.

In general notes on analysis you can find some remarks on abbreviations, notation and concepts. Some books that I have been consulting can be found in consulted literature. At least all references made to literature in the notes should relate to entries in the consulted literature. The music examples are made in Musescore 4.

Sonata form terminology

The first movement is written in the sonata form. Entire books have been written about the sonata form that contain a wealth of information on this concept. Here I am only concerned with the terminology being used. Any self-respecting author creates her/his own names for the various components of the sonata form. Usually there is an agreement on the names of the high level parts:

exposition – development – recapitulation

The terminology on the next (lower) level is more diverse. The sonata form is characterised by the statement of an opening theme in the main or home key. What follows (usually after a component called the Transition) is a contrasting section that differs always in the key being used and possibly also in the melodic/motivic material. These two components of the exposition boast quite a variety of naming. Table 1 provides some of the designations that can be found in the recent literature.

opening theme

contrasting section

Laitz[2]Steven G. Laitz, The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis and Listening (4th Ed, New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2016), Chapter 27: Sonata form.

First tonal area (FTA)

Second tonal area (STA)

Caplin[3]William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998), Chapter 13: Sonata form.

Main Theme

Subordinate Theme

Hepokoski & Darcy[4]James A. Hepokoski and Warren Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), Chapter 2: Sonata form as a whole.

Primary theme/idea (P)

Secondary theme zone (S)

Table 1: some naming of the two theme or key areas in the sonata form

In what follows I will use the terminology proposed by Hepokoski & Darcy as opposed to what I used in the post Comparing the Schumann string quartets. The main reason for the change being the theory of Hepokoski & Darcy on the type 2 sonata form.[5]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, Chapter 17. That theory shows the need to distinguish between different combinations of keys and themes.

For the two other components of the exposition, the Transition (TR) and the Closing Section or Zone (CS), authors generally use more or less the same designation.

Notational convention for major and minor keys

As for a notational convention of major and minor keys: I will use capitals for major keys and lower-case letters for minor keys. For major keys I will often add the word major and for minor keys the word minor, but in music examples and diagrams the words major and minor will in general be omitted. So B major or B for B major and b minor or just b for b minor.

Most suitable devices

Finally it must be mentioned that although automatic adjustments are made to view these posts on tablets as well as mobile phones, they can best be accessed on a computer/laptop. The reason being that there are various tables and lists (like abbreviations) of which the columns will appear one beneath the other (especially on a mobile phone). If that is the case the coherence will be lost.

Beethoven: the piano trio in B-flat major, op.11

First movement: Allegro con brio

Global structure

The Allegro con brio is in sonata form and contains the following elements:

Measure

1-105

106-156

157-254

Section

Exposition

Development

Recapitulation

Key (relative to B-flat major)

I – V

IIIMD – V

I

Table 2: layout of the first movement

The Development

A downloadable PDF of the complete Development with my annotations can be found here.

The development contains the following elements:

Measure

106-116fb

116-123fb

123-137fb

137-143fb

143-156

Section

pre-core

1) S0 module material

2) P theme: u1 motive

core

3) sequence A2(-3/+4) + 2 bars

4) learned style harmonic transition

exit/standing on the dominant

5) dominant lock

Key (relative to B-flat major)

IV/IIIMD – IIIMD

IIIMD

IIIMD – V/vi (vi:HC)

V/vi – V

V

Table 3: layout of the Development [fb=first beat]

Overall view of the Development

This paragraph tries to give an idea of the main structure of the development. The various (sub-)sections will be discussed separately below. As shown in table 3, I recognise three main sections in the development: the pre-core, the core and the exit or standing on the dominant. These find their origin in the model for the analysis of development sections which Hepokoski and Darcy call: Sequence-blocks: the Ratz-Caplin model.[6]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 228-229. This model distinguishes the three mentioned sections and I think that is applicable here.

The pre-core is an introductory section. It is in the key of D-flat major and consists of an establishment of the subdominant IV (G-flat major) in the style of the S0 module of the exposition. This is followed by a cadence in D-flat major and then the main theme follows in this key (mm.116-123fb).

The next main section is the core (Caplin)[7]Caplin, Classical Form, 141-142. or Kern der Durchführung (Ratz)[8]Erwin Ratz, Einführung in die musikalische Formenlehre: Über Formprinzipien in den Inventionen J.S. Bachs und ihre Bedeutung für die Kompositionstechnik Beethovens (Wien: Universal edition, 1968), 32.. This section consists of an ascending second sequence [A2(-3/+4)] which takes us from D-flat major to g minor. But in fact g minor is not confirmed and the progression gets stuck on the dominant of g minor, being D major. This D major is to be interpreted as the dominant of the vi (g minor) of B-flat major (V/vi). B-flat major is the home key of the movement (and the piece as a whole). I will come to the tonal layout of the development in a minute.

D major is prolonged with a dominant lock (the dominant of vi, mm.133-137fb) and then there follows a contrapuntal (learned style) harmonic transition to the dominant of the home key, F major.

This active dominant VA (F major) is firmly established with a standing on the dominant or dominant lock of 14 bars (mm.143-156) which is the third and last main section of the development.

The tonal layout of the Development

So let’s look at the harmonic progression in this development. The start is already remarkable: D-flat major. How to interpret this key? I think there are two perspectives from which you can look at it: from B-flat major (the home key of the movement) and F major, the dominant and the key of the secondary theme zone of the exposition.

I will start from the perspective of F major. In F major, D-flat major is the VIMD. Look here for some explanation of MD (= moll dur). The A2 sequence takes this to D major, which turns out to be the dominant of g minor. g minor does not fit in D-flat major and should – as mentioned before – be interpreted as the vi of B-flat major. D-flat major can however also be interpreted as the IIIMD of B-flat major and thus we can see the whole harmonic scheme of the development in the light of home key to which the development will eventually lead of course in the recapitulation.

When looking back at the S0 module of the exposition, it started with a D major chord which was interpreted as the dominant of g minor, the subdominant ii of F major. But what if we interpret the g minor as the vi of B-flat major which is subsequently interpreted as the ii of F major? Then we have a kind of symmetrical construction:

- in the exposition the progression is from B-flat major to g minor by way of its applied dominant D major. g minor was interpreted as the ii of F major. But in retrospect it can also be interpreted as the vi of B-flat major.

- in the development the progression is from F major (end of exposition) to D-flat major (VIMD) reinterpreted as the IIIMD of B-flat major.

So in both cases the harmonic transition starts with a triad on the sixth scale degree of the prevailing key which is then reinterpreted in the key to come. My hypothesis is that Beethoven is playing with the third relationships of the home key (B-flat major) and its dominant (F major). g minor as the vi of B-flat major and the ii of F major; and D-flat major as the VIMD of F major and the IIIMD of B-flat major.

The ascending second sequence brings D-flat major to the V/vi (D major) of B-flat major. Again the (applied) dominant of g minor plays an important role as the V/vi. The V/vi is according to Hepokoski and Darcy the second level default for ending a development section (the first level default of course being the dominant of the home key).[9]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 198-205.

D major plays an important role in the exposition (the S0 module) and can perhaps be seen as a forward reference to its role as the V/vi in the development. In this development it is not the end. What follows is a harmonic progression (mm.137-143fb) to still arrive at the dominant of the home key (VA: F major).

Figure 1 tries to summarise this idea in a diagram.

fig.1 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, harmonic layout of the first movement

I will now turn to the individual sections of the development.

The sections of the Development

The first section

Figure 2 shows the first section of the pre-core. It is clearly the material from the S0 section that introduced the secondary theme zone in the exposition. Whereas in the exposition the first four bars of S0 lead to g minor, the subdominant ii of F major, here it leads to G-flat major (m.110fb), the subdominant IV of D-flat major. The harmonic progression is identical, except that Beethoven uses an applied dominant seventh chord in the second half of m.108.

fig.2 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, development – section 1

The remainder of the phrase consists of a somewhat more extended cadential progression than in the exposition and is closed with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC, mm.115-116). With this, the key of D-flat major is firmly established. Notice the nearly chromatic descendant bass-line from m.112 onwards. The A natural in the bass on the fourth beat of m.111 (an incomplete neighbour note) does not fit in the chord but is a prelude to the chromatic progression in the main theme (P) which is played by the cello from m.116 onwards. This is the subject of the next section.

The second section

Figure 3 shows the second (and last) section of the pre-core. It is the u1 motive of the main theme P (exposition, fig.3), first played by the cello and then by the clarinet. The key is D-flat major whose role has been discussed in the paragraph on the tonal layout of the development.

fig.3 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, development – section 2

The form resembles very much a parallel period be it that the antecedent (mm.116-119fb) is concluded with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC). As explained in my post on the period that is not the normal course of events. It feels however less strong than the second PAC (mm.122-123) because the clarinet immediately (after the first beat) moves forward to the next phrase whereas in m.123 the final chord lasts three beats, and feels more as a rest point.

This concludes the introduction of the development (the pre-core) which consists of the establisment of the key of D-flat major (section 1) and a citation of the P theme in that key, in fact the ”real” introduction of the development (section 2).

The third section

This is where the body or core of the development starts. Recall that the model I use for the analysis is called the Sequence-blocks: the Ratz-Caplin model (mentioned in the paragraph on the overall view of the Development). The sequence-blocks refer to the core of the development. The third section is in fact the only real sequence block in this development and starts with a first occurrence (or model) of the sequence (mm.123-126). Following are two copies of this model (mm.127-134), be it that the second copy has a deviant ending and modulates away from D-flat major.

Figure 4 shows the first occurrence of the sequence.

fig.4 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, development – section 3 – model of the sequence

As has already been indicated this is an ascending second sequence A2(-3/+4) which means that in one occurrence the chords go a third down and then in passing to the next occurrence a fourth up. Figure 4 shows one occurrence, so one should be able to find the descend of a third. This is found at the end of m.124 where the transition from D-flat major to the B-flat dominant seventh chord is made. This chord is the dominant seventh of e-flat minor, the start of the first copy (and second occurrence) in the sequence. The transition is made by way of the vii02 of e-flat minor, a d-diminished chord (fourth beat of m.124). Notice the descending bass line which is in fact the c1 motive of the main theme (exposition: fig.3).

Figure 5 shows the harmonic progression in this occurrence.

fig.5 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, development – section 3 – harmonic progression

As one can see Beethoven continues the descending bass line from D-flat2 to C-flat2. By making at the same time a chromatic alteration (D-flat4 becomes D natural4) the progression is from D-flat major to the d-diminished chord in third inversion (d02). This chord can be seen as a B-flat dominant ninth chord without the root. In the next step the ninth (C-flat) becomes B-flat and the chord has found its root and becomes a dominant seventh chord. The F natural and A-flat are the common tones in this progression.

The cello and clarinet play the c1 motive in an imitative way over the B-flat dominant seventh chord which leads to the next occurrence of the sequence which starts (not surprisingly) in e-flat minor (the ii of D-flat major). e-flat minor being both a fourth up (+4) with respect to the B-flat dominant seventh chord and a second up (A2) with respect to D-flat major.

The second occurrence (mm.127-130) is not shown here but can be found in the downloadable PDF of the development. It is exactly the same as the model of the sequence but diatonically raised one second. This leads to the third occurrence (or second copy) of the sequence. Figure 6 shows the third occurrence and – as mentioned earlier – this occurrence takes a different turn.

fig.6 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, development – section 3 – third occurrence of the sequence

In m.131 f minor (the iii of D-flat major) is reached. Completely diatonically in the scale of D-flat major. On the fourth beat of m.132 however a f-sharp diminished chord in third inversion is found leading to a D major seventh chord on the first beat of m.133. This is absolutely not in line with a diatonic progression in D-flat major.

To see this fig.7(a) shows what a diatonic continuation of the ascending second sequence would have looked like.

fig.7 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, development – section 3 – alternative for the third occurrence

The entire sequence is included in the figure and the notation is consistent with Job IJzerman’s notation for the chromatic Monte.[10]Job IJzerman, Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 2018), 216-217. Just as a reminder: the A2(-3/+4) sequence is a Galant style Monte. Look here for a brief explanation of the Galant style and the prototype of a chromatic Monte. In essence, every step of a second is represented as a tonicization. So in the tonicization of ii we find a vii02 and a V7 of ii. The same applies to the tonicization of iii.

Again, if the sequence were to be continued diatonically it would have looked like fig.7(a). As shown the third occurrence would have led to G-flat major, the IV of D-flat major. This step is different from the previous two because there is no passing note to the next root (from f minor to G-flat major). The reason being that between the first and second scale degree – and between the second and third scale degree – there is a whole tone which can be filled with a chromatic passing note (the root respectively the third in the vii02 and V7 chords). Between the third and fourth scale degree there is only a semitone difference, so no chromatic passing note is possible. That is why the F natural in the f minor-, the f diminished- and the D-flat dominant seventh chord remains a common tone.

But what did Beethoven do? This is shown in fig.7(b). He did not proceed to G-flat major but to (the dominant of) g minor. So he smuggles in a whole tone distance, from f minor to g minor and inserts the chromatic passing note f-sharp – harmonized with the f#02 chord – which is subsequently altered into the D dominant seventh chord (as in the previous two occurrences of the sequence). He continues the sequence in a consistent but (therefore) not diatonic manner by ignoring the diatonic semitone distance between the third and fourth scale degree.

In fact this is a modulation to B-flat major – the home key – because the D dominant seventh chord should be interpreted as the V/vi (in B-flat major). As mentioned in the paragraph on the tonal layout of the Development the g minor chord is never reached as there is a lock on the dominant of g minor (mm.133-137fb). We do catch a glimpse of g minor as the neighbour chord of the dominant (V64) in m.135 but this is merely an embellishment (and extension) of the dominant D major. See the paragraph on the fifth section for an explanation of the functions of the V64 chord.

The third section ends with a half cadence (HC) in g minor (vi:HC, m.137), which is preceded by the diminished seventh of D major (m.136).

At this point a return to the main theme in the home key would have been possible (the recapitulation).[11]Beethoven did this in the violin sonata in F major, op. 25 “Frühling” where the development ends on A major, the dominant of d minor (V/vi), d minor being the vi of F major. Example cited from Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 199. But that is not what Beethoven did. The next section shows how he makes the transition to the dominant of the home key, F major.

The fourth section

Figure 8 shows the fourth section. It is in – what Leonard Ratner would call – the learned style.[12]Leonard G. Ratner, Classic Music: Expression, Form, and Style (New York: Schirmer Books, 1980), 23-24 and chapter 15.

fig.8 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, development – section 4

That is an imitative (contrapuntal) style with, in this case, three entries in the clarinet, right hand of the piano and cello respectively. It reminds one of mm.13-16 of the external extension of the main theme (exposition, fig.1). Counting in the fortepiano entry in the left hand of the piano in m.140 one can identify a falling fifth sequence in the subsequent entries: D-G-C-F. The harmonies however are the result of the contrapunt and do not support the falling fifth sequence.

On the F-natural pedal (mm.140-143) again an embellishing V64 is found in the first half of m.142. In fact the harmonic progression in mm.141-143fb is the same as in mm.133-137fb of the third section (fig.6), the first one mentioned in g minor and the second one in B-flat major. From m.141 onwards we are on F major, as active dominant of B-flat major to which we are about to return in the recapitulation, but only after an extended standing on the dominant of fourteen measures. That is the subject of the fifth and last section of the development.

The fifth section

This section is a standing on the dominant[13]Caplin, Classical Form, 144-145. or dominant lock[14]Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 19., where the dominant should be related to B-flat major. So the section is on F major, an active dominant VA, and can be structured as follows: 4+4+1+1+4.

Figure 9 shows the first phrase of 4 measures which run from the third beat of m.143 to the second beat of m.147.

fig.9 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, development – section 5, first phrase

The first thing that stands out is the pedal on F major (as always shown in green). Secondly again a variant of the c1 motive (exposition: fig.3) is found in the left hand of the piano. This accounts for a variety of chord inversions but they should be interpreted as a consequence of the counterpoint. So there are only two harmonies: F major and b-flat minor, the last one of which is essentially in second inversion. Therefore the mm.145-146 should be interpreted (as has been found in the fourth section) as an embellishing V64.

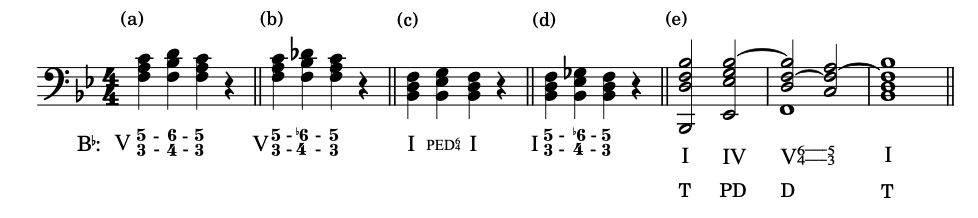

Figure 10 explains the various functions and varieties of the V64 chord.

fig.10 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, functions and varieties of the V64 chord

Figure 10(a) shows the V64 chord as an embellishment of the dominant V53 chord. The V64 chord can be seen as a double neighbour note over a pedal (the F natural). Figure 10(b) shows the same progression, but whereas in example (a) the neighbour notes are diatonic, example (b) uses a form of modal mixture: the sixth is lowered (the D-flat). So here both neighbour notes are a semitone above the main pitch which gives the prolongation of the V chord a special flavour, that of the parallel minor of the tonic B-flat. This is the variant used in mm.145-146 (and also in m.135 and m.142).

Examples (c) and (d) show the same progression but with a starting chord that has a different function (i.e. that of a tonic). Example (c) shows the label that Laitz uses for these six-four chords over a pedal: PED64.[15]Laitz, The Complete Musician, 304-305. Example (e) shows the well-known use of a V64 chord in a cadential progression. In these cases it is also called a cadential six-four chord. It is a suspension which resolves to the dominant chord V53.

In m.146 the clarinet and cello play the e4 related motive from the S0 module (fig.2, m.109 and exposition: fig.3).

The next four bar phrase (m.147 third beat to m. 151 second beat) is an exact copy of the first four bar phrase. What follows are two bars (mm.151-153fb) as shown in fig.11.

fig.11 Beethoven: piano trio op.11, i, development – section 5, third and fourth phrase

The harmonic rhythm is four times as fast as in the previous bars and only a reminiscence of the e4 related motive is left (also called liquidation). And then remains an F major scale ending on an F natural with neighbour note (m.156). In m.157 the recapitulation starts.

This concludes the analysis of the development of the first movement of this trio.

Notes

| ↩1 | Karol Berger, Bach’s Cycle, Mozart’s Arrow: An Essay on the Origins of Musical Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), Postlude. |

|---|---|

| ↩2 | Steven G. Laitz, The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis and Listening (4th Ed, New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2016), Chapter 27: Sonata form. |

| ↩3 | William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 1998), Chapter 13: Sonata form. |

| ↩4 | James A. Hepokoski and Warren Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press, 2006), Chapter 2: Sonata form as a whole. |

| ↩5 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, Chapter 17. |

| ↩6 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 228-229. |

| ↩7 | Caplin, Classical Form, 141-142. |

| ↩8 | Erwin Ratz, Einführung in die musikalische Formenlehre: Über Formprinzipien in den Inventionen J.S. Bachs und ihre Bedeutung für die Kompositionstechnik Beethovens (Wien: Universal edition, 1968), 32. |

| ↩9 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 198-205. |

| ↩10 | Job IJzerman, Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York [ect.]: Oxford University Press, 2018), 216-217. |

| ↩11 | Beethoven did this in the violin sonata in F major, op. 25 “Frühling” where the development ends on A major, the dominant of d minor (V/vi), d minor being the vi of F major. Example cited from Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 199. |

| ↩12 | Leonard G. Ratner, Classic Music: Expression, Form, and Style (New York: Schirmer Books, 1980), 23-24 and chapter 15. |

| ↩13 | Caplin, Classical Form, 144-145. |

| ↩14 | Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 19. |

| ↩15 | Laitz, The Complete Musician, 304-305. |

Recent Comments